By Alan Buis

NASA's Global Climate Change Website

Part 1 of a Two-Part Series

If you could ask a sea turtle why small increases in global average temperature matter, you’d be likely to get a mouthful. Of sea grass, that is.

Of course, sea turtles can’t talk, except in certain animated movies. And while on-screen they’re portrayed as happy-go-lucky creatures, in reality it’s pretty tough to be a sea turtle, dude (consider the facts), and in a warming world, it’s getting tougher.

Since the temperature of the beach sand that female sea turtles nest in influences the gender of their offspring during incubation, our warming climate may be driving sea turtles into extinction by creating a shortage of males, according to several studies.1

A few degrees make a huge difference. At sand temperatures of 31.1 degrees Celsius (88 degrees Fahrenheit), only female green sea turtles hatch, while at 27.8 degrees Celsius (82 degrees Fahrenheit) and below, only males hatch.

While the plight of sea turtles is illustrative, it’s a fact that all natural and human systems are sensitive to climate warming in varying degrees. To assess the likely impacts of global warming on our planet at various temperature thresholds above pre-industrial levels (considered to be the time period between 1850 and 1900), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in October released a Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 Degrees Celsius (2.7 Degrees Fahrenheit). The IPCC is the United Nations body tasked with assessing the science related to climate change.

The report examined the impacts of limiting the increase in global average temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, and projected the impacts Earth is expected to see at both 1.5 degrees and 2 degrees Celsius warming above those levels. The 1.5-degree Celsius threshold represents the target goal established by the Paris Agreement, adopted by 195 nations in December 2015 to address the threat of climate change.

Selected Impacts of Additional Global Warming of 0.5 - 1º Celsius

Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5º Celsius (2.7º Fahrenheit)

For a more detailed overview of selected highlights from the IPCC Special Report, see A Degree of Concern, Part 2.

Warmest Temperature Extremes

The warmest extreme temperatures will be in Central and Eastern North America, Central and Southern Europe, the Mediterranean (including Southern Europe, Northern Africa and the near-East), as well as Western and Central Asia and Southern Africa.

Heatwaves

At 2 degrees Celsius warming, the deadly heatwaves India and Pakistan saw in 2015 may occur annually.

Water Availability

By limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, up to half as many people around the planet may experience water stress caused by climate change, depending on future socioeconomic conditions. The degree will vary from region to region. People in river basins, especially in the Middle and Near East, will be particularly vulnerable.

Extreme Precipitation

At 2 degrees Celsius warming, some places will see an increase in heavy rainfall events compared to at 1.5 degrees warming. This includes Eastern North America, which will see higher flooding risks. Other affected areas include the Northern Hemisphere high latitudes (Alaska/Western Canada, Eastern Canada/Greenland/Iceland, Northern Europe, Northern Asia) and Southeast Asia.

Impacts on Biodiversity and Ecosystems

At 1.5 degrees Celsius warming, 6 percent of the report's studied insects, 8 percent of plants and 4 percent of vertebrates will see their climatically determined geographic range reduced by more than half (map highlights areas where monarch butterfly populations are affected). At 2 degrees Celsius warming, those numbers jump to 18 percent, 16 percent and 8 percent, respectively.

Forest Impacts

Warming of 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius will lead to a reduction of rainforest biomass and will increase deforestation and wildfires. Trees at the southern boundaries of boreal forests will die.

Ocean Impacts

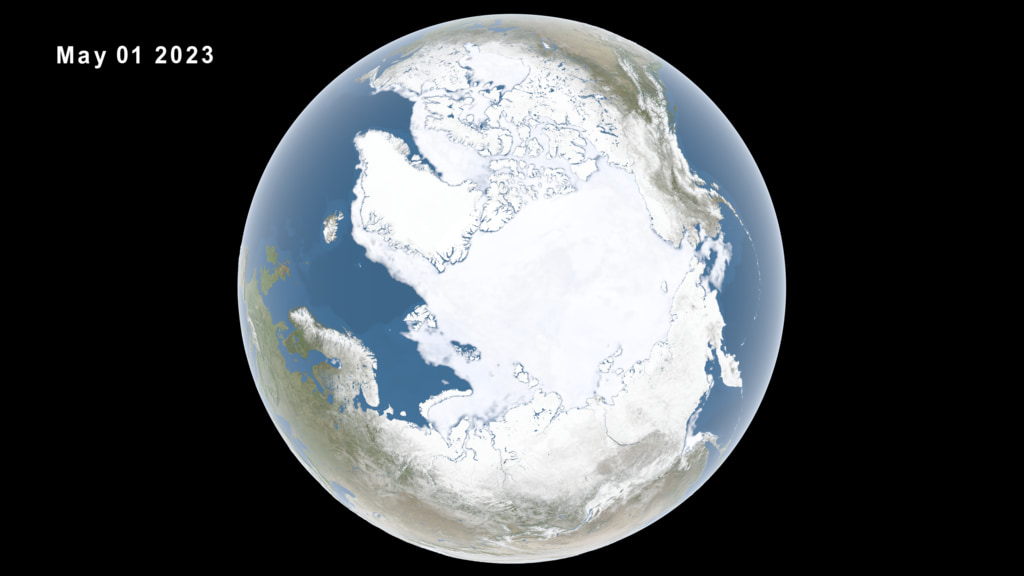

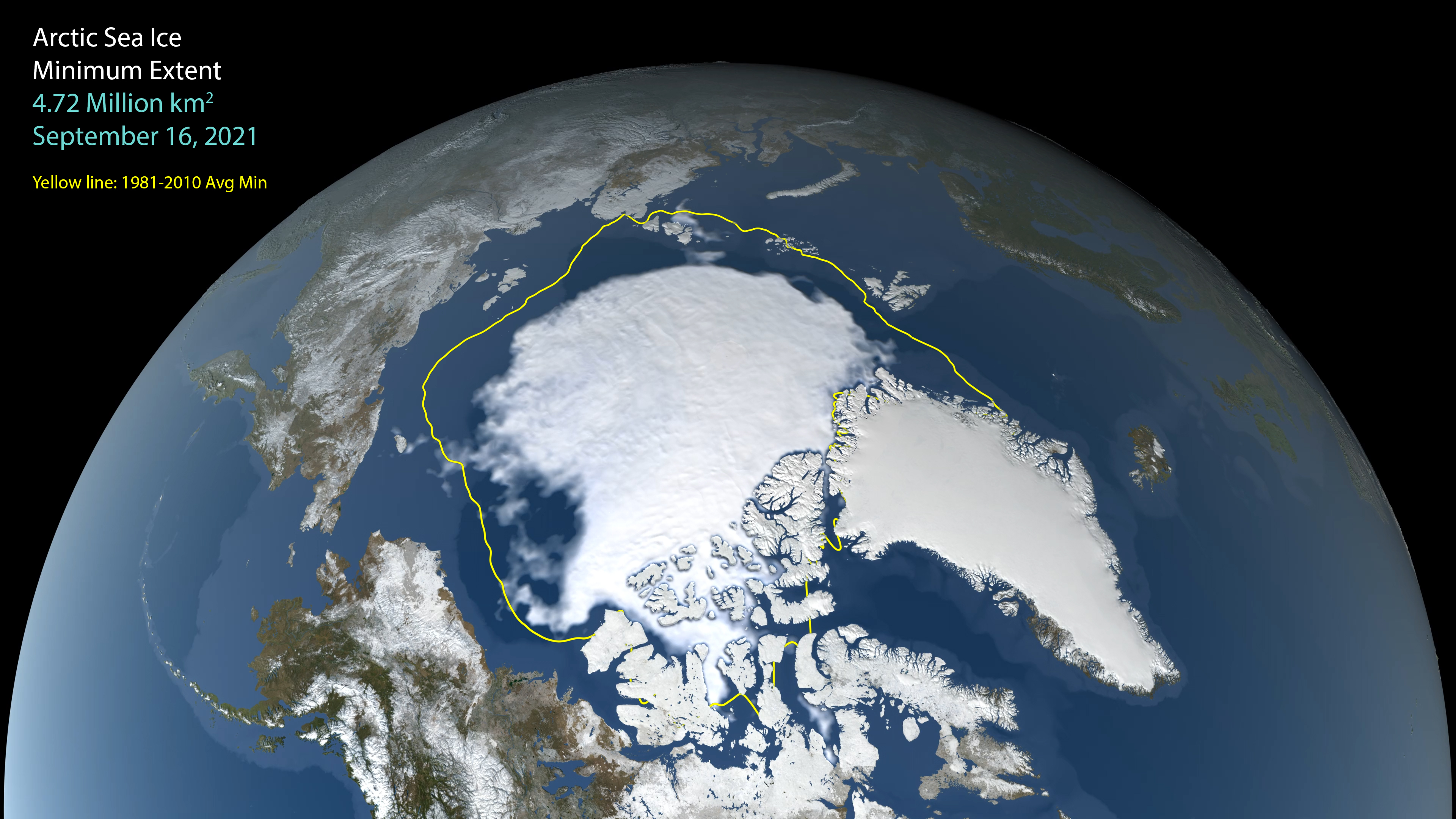

The IPCC Special Report states, with medium confidence, that at an increased level of warming between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius, instabilities in the Antarctic ice sheet and/or the irreversible loss of the Greenland ice sheet could lead to multi-meter (greater than 6 feet) sea level rise over a time scale of hundreds to thousands of years.

Marine Life

Ocean oxygen levels will decrease, leading to more “dead zones” — areas where normal ocean waters are replaced by waters with low oxygen levels that won’t support most aquatic life.

Coral Reef Impacts

Ocean warming, acidification and more intense storms will cause coral reefs to decline by 70 to 90 percent at 1.5 degrees Celsius warming, becoming all but non-existent at 2 degrees warming.

Impacts on Humans

The risk of heat-related illness and death will be lower at 1.5 degrees Celsius warming than at 2 degrees. Cities will experience the worst impacts of heatwaves due to the urban heat island effect, which keeps them warmer than surrounding rural areas.

Food Shortages

Projected food availability will be less at 2 degrees Celsius warming than at 1.5 degrees in Southern Africa, the Mediterranean, the Sahel, Central Europe and the Amazon.

Economic Impacts

In the United States, economic damages from climate change are projected to be large, with one 2017 study concluding the United States could lose 2.3 percent of its Gross Domestic Product for each degree Celsius increase in global warming.

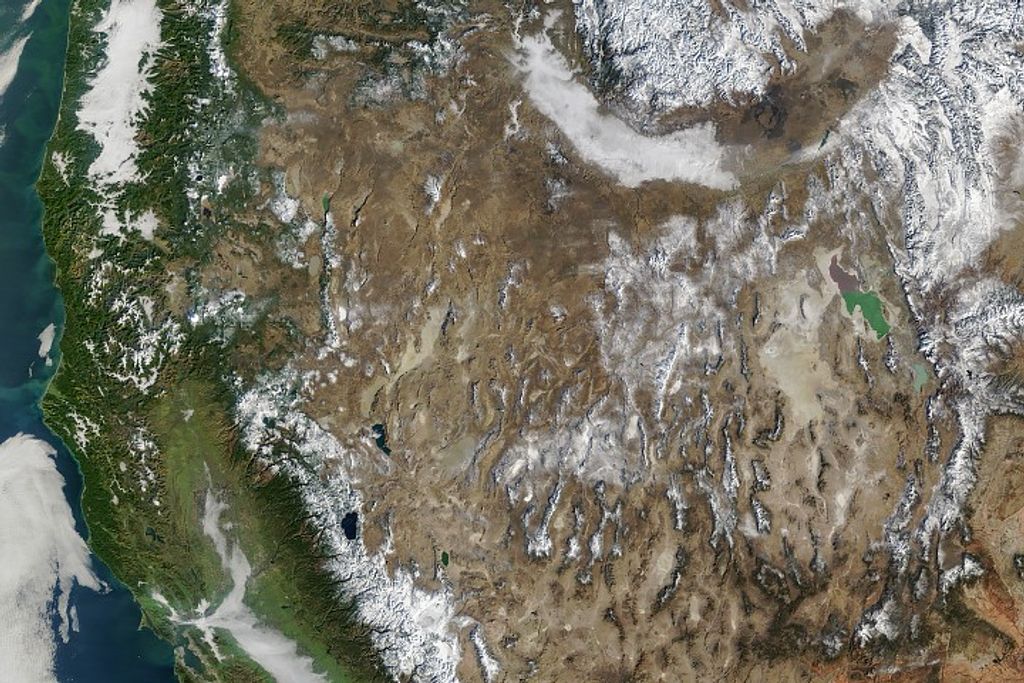

Droughts

The report finds that limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius is expected to significantly reduce the probability of drought and risks related to water availability in some regions, particularly in the Mediterranean (including Southern Europe, Northern Africa and the Near-East), and in Southern Africa, South America and Australia.

The report, prepared by 91 authors and review editors from 40 countries along with 133 contributing authors, cites more than 6,000 scientific references and includes contributions from thousands of expert reviewers around the world, including from NASA. NASA data were critical to enabling understanding of how each half degree of warming will impact our planet. NASA models contributed to the report’s projections, while NASA satellite and airborne observations provided critical inputs.

“Unfortunately, warming has progressed so much that we now have observations of what happens when you have an extra half a degree,” said Drew Shindell, professor of Climate Sciences at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. Shindell is a coordinating lead author of one chapter of the Special Report and an author of its Summary for Policy Makers. “Having an extra five to 10 years since the last IPCC Assessment, along with modern monitoring systems, many of which are from NASA, really lets us see what happens to the planet with an extra half a degree of warming much more clearly than in the past.”

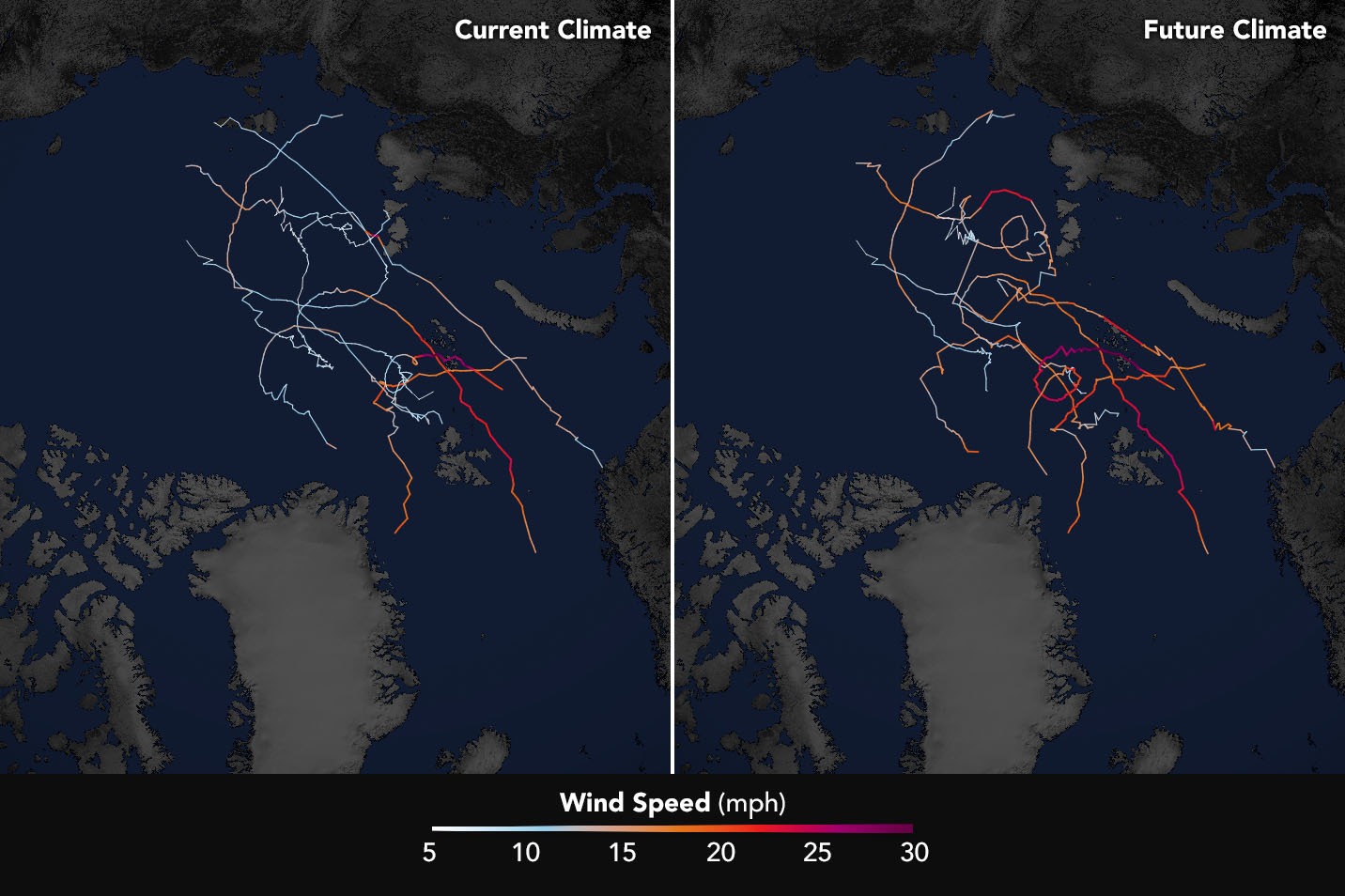

The report says that since the pre-industrial period, human activities are estimated to have increased Earth’s global average temperature by about 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit), a number that is currently increasing by 0.2 degrees Celsius (0.36 degrees Fahrenheit) every decade. At that rate, global warming is likely to reach 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels sometime between 2030 and 2052, with a best estimate of around 2040.

Warming that’s already been introduced into the Earth system by human-produced emissions since the start of the pre-industrial period isn’t expected to dissipate for hundreds to thousands of years. That already “baked in” warming will continue to cause further long-term changes in our climate, such as sea level rise and its associated impacts. However, the report says that these past emissions alone are not considered likely, by themselves, to cause Earth to warm by 1.5 degrees Celsius. In other words, what we as a society do now matters. The urgency with which the world addresses greenhouse gas emission reductions now will help determine the degree of future warming; in essence, whether we’ll be hit by a climate change hardball or a wiffle ball.

You might be thinking, “Why should I care if temperatures go up another half a degree or one degree? Temperatures go up and down all the time. What difference does it make?”

The answer is, a lot. Higher temperature thresholds will adversely impact increasingly larger percentages of life on Earth, with significant variations by region, ecosystem and species. For some species, it literally means life or death.

“What we see isn’t good – impacts of climate change are in many cases larger in response to a half a degree (of warming) than we’d expected,” said Shindell, who was formerly a research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City. “We see faster acceleration of ice melting, greater increases in tropical storm damages, stronger effects on droughts and flooding, etc. As we calibrate our models to capture the observed responses or even simply extrapolate another half a degree, we see that it’s more important than we’d previously thought to avoid the extra warming between 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius.”

Shindell said the report was able to use scientists’ understanding from observations to assess how many more people would be at risk from the impacts of climate change with an additional half a degree of warming. “It’s hundreds of millions,” he said, “which makes clear the importance of keeping warming as low as possible.”

NASA’s global climate change website, and its vital signs section, document what a 1-degree Celsius temperature increase has already done to our planet. The impacts of global warming are being felt everywhere, from rising sea levels to more extreme weather, more frequent wildfires, and heatwaves and increased drought, to name a few. Because our society has been built around the climate Earth has had for the past approximately 10,000 years, when it changes noticeably, as it has done in recent decades, people begin to take notice. Today, most people realize Earth’s climate is changing. A December 2018 report by Yale and George Mason Universities found that seven in 10 Americans think global warming is happening, with about six in 10 saying it is mostly caused by humans.

We live in a world bound by the laws of physics. For example, at temperatures above 0 degrees Celsius (32 degrees Fahrenheit), ice, including Earth’s polar ice sheets and other land ice, begins to melt and changes from a solid to a liquid. When that water flows downward into the ocean, it raises global sea level.

Similarly, temperature plays a critical role in biology. We all know the average temperature of a healthy adult human is about 37 degrees Celsius (98.6 degrees Fahrenheit). You don’t have to ask anyone running a fever of 38.3 degrees Celsius (101 degrees Fahrenheit) if a couple of degrees matters. Our bodies are optimized to run at a certain temperature. According to most studies, humans feel most comfortable, are most productive and function best when the ambient temperature around us is roughly 22 degrees Celsius (71.6 degrees Fahrenheit). Vary that temperature by more than a few degrees in either direction and we seek to warm or cool ourselves if we can. Our bodies also make adjustments, such as sweating.

When ambient temperatures become too extreme, the impacts on human health can be profound, even deadly.

Plants and other animals have it tougher. While they also adjust to their external temperature environment through various mechanisms, they can’t just turn on an air conditioner or furnace like we can, and they may not be able to migrate. They survive within specific, defined habitats.

For all living organisms, the faster climate changes, the more difficult it is to adapt to it. When climate change is too rapid, it can lead to species extinction. As greenhouse gas concentrations continue to increase, the cumulative impact will be to accelerate temperature change. Limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius decreases the risks of long-lasting or irreversible changes, such as the loss of certain ecosystems, and allows people and ecosystems to better adapt.

So just how may another half- or full-degree Celsius of warming affect our planet? In part two of our feature, we look at some of the IPCC special report’s specific projections.

Reference

- E.g., Jensen, Michael & Allen, Camryn & Eguchi, Tomoharu & P. Bell, Ian & L. LaCasella, Erin & A. Hilton, William & Hof, Christine & H. Dutton, Peter. (2018). Environmental Warming and Feminization of One of the Largest Sea Turtle Populations in the World. Current Biology. 28. 154-159.e4. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.11.057.