Lunar Ranger and Surveyor Programs

The Ranger and Surveyor projects of the 1960s were among the first U.S. efforts to explore another body in space: the Moon.

Mission Type

Missions

First Launch

Final mission

Begun at the beginning of the 1960s as ambitious, independent and broad scientific activities, the Rangers and Surveyors paved the way for the eventual Apollo human exploration missions to the Moon.

Rangers were designed to relay pictures and other data as they approached the Moon and finally crash-landed into its surface. The Surveyors were designed for lunar soft landings.

The Ranger Program

| Spacecraft | Launch Date | Purpose | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ranger 1 | Aug 23, 1961 | Lunar Prototype | Unsuccessful |

| Ranger 2 | Nov 18, 1961 | Lunar Prototype | Unsuccessful |

| Ranger 3 | Jan 26, 1962 | Impact Probe | Unsuccessful |

| Ranger 4 | Apr 23, 1962 | Impact Probe | Unsuccessful |

| Ranger 5 | Oct 18, 1962 | Impact Probe | Unsuccessful |

| Ranger 6 | Jan 30, 1964 | Impact Probe | Unsuccessful |

| Ranger 7 | Jul 28, 1964 | Impact Probe | Successful |

| Ranger 8 | Feb 17, 1965 | Impact Probe | Successful |

| Ranger 9 | Mar 21, 1965 | Impact Probe | Successful |

Ranger was originally designed, beginning in 1959, in three distinct phases, called “blocks.” Each block had different mission objectives and progressively more advanced system design. The JPL mis- sion designers planned multiple launches in each block, to maximize the engineering experience and scientific value of the mission and to assure at least one successful flight.

Block 1, consisting of two spacecraft launched into Earth orbit in 1961, was intended to test the Atlas/Agena launch vehicle and spacecraft equipment without attempting to reach the Moon.

Most elements of spacecraft technology taken for granted today were untested before Ranger. Perhaps the most important of these was three-axis attitude stabilization, meaning that the spacecraft is fixed in relation to space instead of being stabilized by spinning. This would permit pointing large solar panels at the Sun, a large antenna at Earth and cameras and other directional scientific sensors at their appropriate targets.

Rocket propulsion carried aboard the spacecraft was another critically important new technology, needed for accurate targeting at the Moon or distant planets.

In addition, two-way communication and closed-loop tracking, requiring spacecraft and ground system development and the use of on-board computing and sequencing combined with commands from the ground, all had to be developed and tried out in flight.

Unfortunately, problems with the early version of the launch vehicle left Ranger 1 and Ranger 2 in short-lived, low-Earth orbits in which the spacecraft could not stabilize themselves, collect solar power or survive for long.

Block 2 of the Ranger project launched three spacecraft to the Moon in 1962, carrying a TV camera, a radiation detector, and a seismometer in a separate capsule slowed by a rocket motor and packaged to survive its low-speed impact on the Moon’s surface. The three missions together demonstrated good performance of the Atlas/Agena B launch vehicle and the adequacy of the spacecraft design, but unfortunately not all on the same attempt.

Ranger 3 was launched into deep space, but an inaccuracy put it off course and it missed the Moon entirely. Ranger 4 had a perfect launch, but the spacecraft was completely disabled. The project team tracked the seismometer capsule to impact just out of sight on the lunar far side, validating the communications and navigation system. Ranger 5 missed the Moon and was disabled. No significant science information was gleaned from these missions.

Ranger’s Block 3 embodied four launches in 1964-65. These spacecraft boasted a television instrument designed to observe the lunar surface during the approach; as the spacecraft neared the Moon, they would reveal detail smaller than the best Earth tele- scopes could show and finally details down to dishpan size. The first of the new series, Ranger 6, had a flawless flight, except that the television system was disabled by an in-flight accident and could take no pictures.

The next three Rangers, with a redesigned television, were completely successful. Ranger 7 photographed its way down to target in a lunar plain, soon named Mare Cognitum, south of the crater Copernicus. It sent more than 4,300 pictures from six cameras to waiting scientists and engineers.

The new images revealed that craters caused by impact were the dominant features of the Moon’s surface, even in the seemingly smooth and empty plains. Great craters were marked by small ones, and the small with tiny impact pockmarks, as far down in size as could be discerned — about 16 inches (50 centimeters). The light-colored streaks radiating from Copernicus and a few other large craters turned out to be chains and nets of small craters and debris blasted out in the primary impacts.

In February 1965, Ranger 8 swept an oblique course over the south of Oceanus Procellarum and Mare Nubium to crash in Mare Tranquillitatis where Apollo 11 would land 4-1/2 years later. It garnered more than 7,000 images, covering a wider area and reinforcing the conclusions from Ranger 7.

About a month later, Ranger 9 came down in the 75-mile-diameter (90-kilometer) crater Alphonsus. Its 5,800 images, nested concentrically and taking advantage of very low-level sunlight, provided strong confirmation of the crater-on-crater, gently rolling contours of the lunar surface.

Thus, after a long trouble-plagued start that taught the system engineers a great deal and the scientists virtually nothing,

Project Ranger finished with three flights that greatly advanced the lunar scientists’ knowledge of the surface and whetted their appetites for a closer look.

The Surveyor Program

| Spacecraft | Launch Date | Purpose | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surveyor 1 | May 30, 1966 | Lunar Lander | Successful |

| Surveyor 2 | Sep 20, 1966 | Lunar Lander | Unsuccessful |

| Surveyor 3 | Apr 17, 1967 | Lunar Lander | Successful |

| Surveyor 4 | Jul 14, 1967 | Lunar Lander | Unsuccessful |

| Surveyor 5 | Sep 8, 1967 | Lunar Lander | Successful |

| Surveyor 6 | Nov 7, 1967 | Lunar Lander | Successful |

| Surveyor 7 | Jan 7, 1968 | Lunar Lander | Successful |

Conceived about the same time as Ranger, the Surveyor project began its development in 1961 with the selection of Hughes Aircraft Co. as spacecraft system contractor to JPL, which managed the project. A different mission, a different launch vehicle and a different way of operating the spacecraft were matched by a different way of developing the project.

NASA originally contemplated delivering more than two dozen scientific instruments to the surface of the Moon with a first launch as early as 1963. Seven missions to different landing sites were planned for the first block. A second-generation design, carrying a small lunar roving vehicle and a non-landing camera platform to map the whole Moon from orbit were studied and begun.

As a near-contemporary of Ranger, the Surveyor project was also an engineering and systems experiment. It would test the high-energy Atlas/Centaur launch vehicle; a new spacecraft design; spacecraft activities directed from the ground, as contrasted with the fixed computer sequence employed in Ranger; and a new and elegant robotic landing method, with three steerable rocket engines controlled by a four-beam spacecraft radar.

Delayed repeatedly by the extended development of the launch vehicle’s Centaur booster and the difficulties of its own development, Surveyor underwent many evolutions of management, engineering and science before successfully landing with a remote-controlled TV camera at Flamsteed in Oceanus Procellarum in June 1966.

The first image from Surveyor 1 showed its own landing foot firmly planted upon lunar soil, mute proof that landing was possible. Detail as small as 1/12 inch (2 millimeters) could bee seen at the closest range. Panoramic mosaics compiled from many of the first Surveyor’s 11,240 TV frames eventually showed nearly the entire landing region, out to the horizon.

Eventually the spacecraft survived many lunar day/night cycles, responding to radio communications until January 1967.

Surveyor 2 was not as successful, crashing into the Moon. Surveyor 4’s signal was lost 2-1/2 minutes after lunar impact.

Surveyor 3, Surveyor 5, Surveyor 6 and Surveyor 7 repeated the initial triumph in different sites and successively added a robot arm with scoop and a chemical element analyzer to the scientific tool kit. The ability to examine lunar soil below the surface and to identify mineral composition in a few sites was scientifically exciting, especially when Surveyor 5’s instrument found basalt and established some history of lunar melting. The determinations of adequate bearing strength in the lunar soil was important for Apollo planning. However, the imaging capability, accumulating almost 90,000 images from five sites, was a very powerful scientific instrument.

The Surveyors observed blocks and craters and other features of the surface down to small size and close range, under different lighting conditions over periods of weeks to months. They were able to compare different terrain types, from plains and different maria (including some future Apollo landing regions) to a small mare crater and finally the flank of the crater Tycho.

All told, three Surveyor lunar stations survived at least one lunar night. One of the spacecraft bounced inadvertently on the surface and another was deliberately flown a few feet (meters) to a second site, extending the reach of the instruments providing jet-disturbed surfaces for examination.

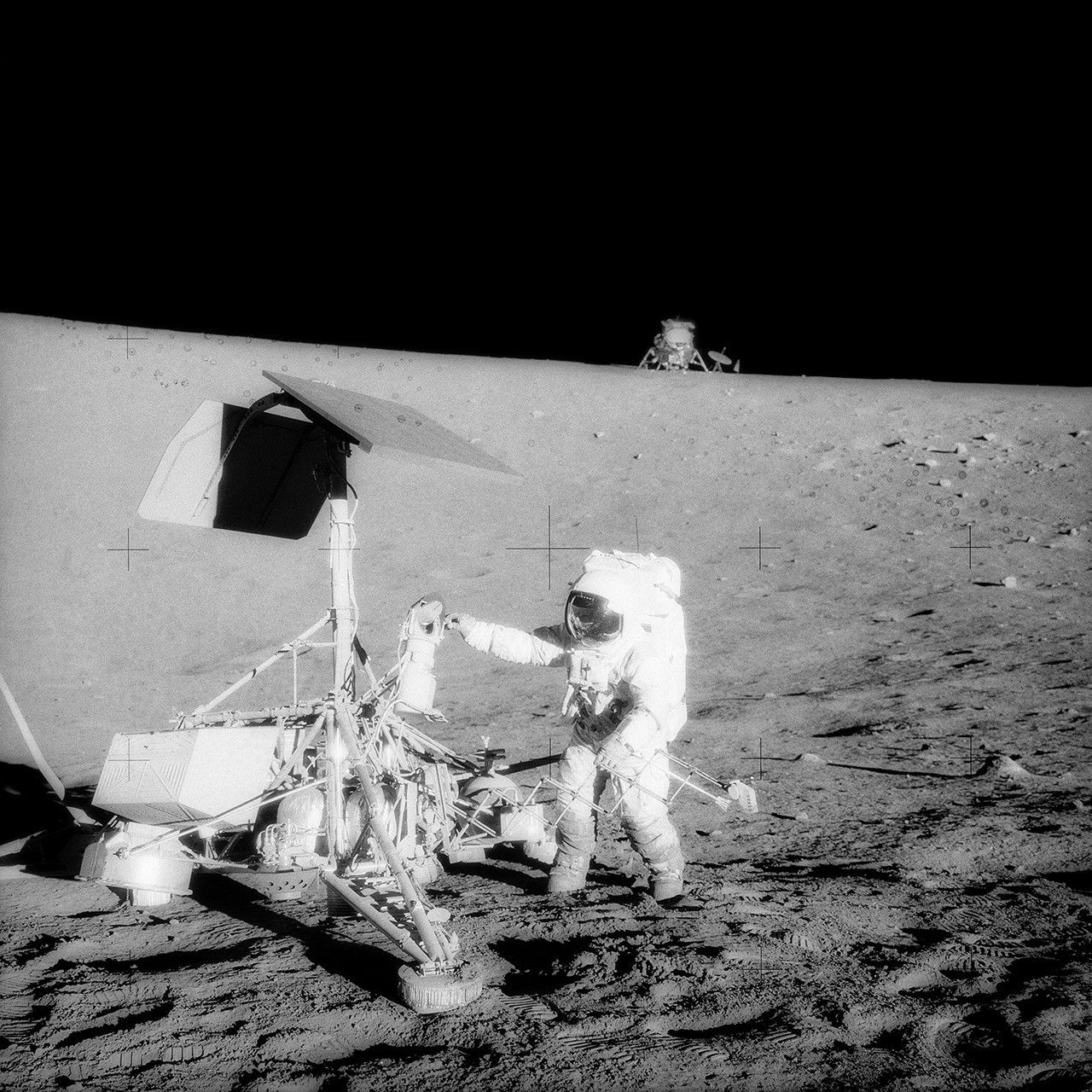

Finally, Surveyor 3 participated in the only lunar surface rendezvous when Apollo 12 landed nearby in November 1969. The astronauts visited the 2-1/2- year-old lunar station photographed it and the site and brought some of its parts back to Earth. The images and samples supported unique and unexpected studies of the effects of exposure to the lunar environment, especially the unimpeded solar-plasma wind.