8 min read

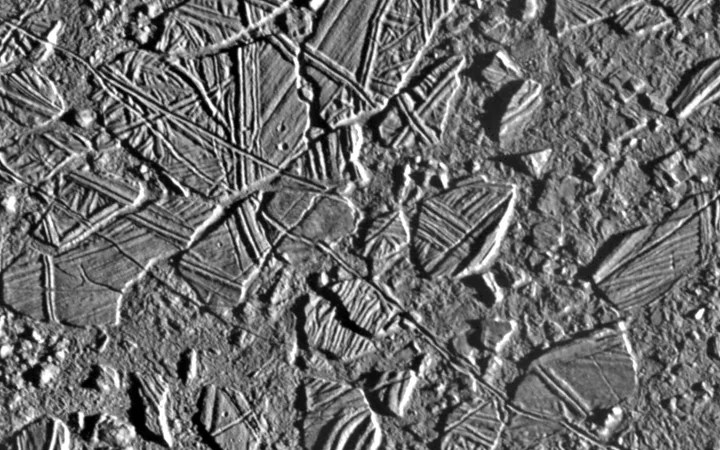

Since water is a clue to habitability, water at Europa is so important. It has really become such a key observation. So being an outer planet satellite scientist concentrating on Europa, one particular image really stands out to me.

Rob Sullivan and I were involved with the planning of Europa images for the Galileo mission. While planning, I had a call from Jeff Moore (from NASA's Ames Research Center). Jeff suggested that we move some of the targeted images to another area, because he had seen something interesting and unusual in the low resolution images taken in an earlier Galileo orbit. Rob and I agreed on this location for imaging, as did Ron Greeley, who was in charge of the Europa planning. This location turned out to be the chaotic region which came to be known as Conamara Chaos (shown above). This image invokes the notion of floating icebergs in an ocean.

The images taken of this area also prompted a press conference to discuss whether this evidence was pointing to an ocean on Europa. It spawned a debate over whether liquid water or solid state ice was involved in shaping Europa's surface. Europa continues to intrigue us. Recently there was a paper published by Britney Schmidt and others explaining how such chaos terrain might form on Europa as related to subsurface lakes within Europa's ice.

It is difficult to convince decision makers that we need to follow-up with a mission to Europa. Europa probably has an ocean underneath its surface -- staring at us and just waiting for exploration. A hundred years from now people are going to look back and say, "Why did it take so long before they explored Europa!" They won't believe it -- that we waited so long. Or for that matter to follow up at Titan, where there are rivers and lakes of methane and ethane. Or to send an orbiter to the Neptune system and observe Triton in order to understand what is powering it. The planet Neptune itself is just so fascinating with its dynamic atmosphere and almost Earth-like blue color. Hopefully, the economy will improve and we will come back to our senses and get back to exploring the solar system. It is frustrating that we are not planning and executing that next encompassing visionary mission to the outer solar system.

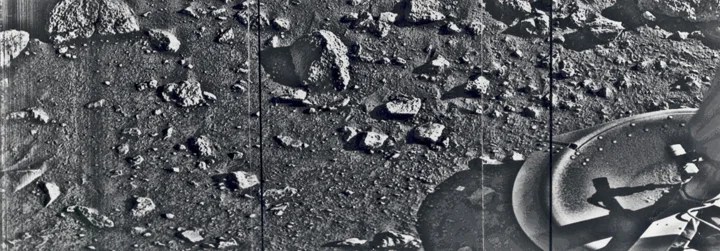

1976: It was so exciting waiting for the twin Viking landers to touch down on the surface of Mars.

I remember sitting at home in late July watching Carl Sagan narrating on TV, while slowly the strips of the first image from Viking 1 came across. It was the image of the landing pad on Mars. It was so thrilling to have that "other world" revealed for the first time. This moment was so moving, and symbolic of my generation's perspective on planetary exploration. (Of course, Venera at Venus happened earlier, but that was so quiet to us in the US, especially given I was a kid back then. It was not until much later that I even knew that it had taken place.)

It is hard to place my thoughts back to a pre-Viking Mars. It was so long ago and I was so young. I know I didn't expect it to look like the southwestern US: After the landing, people said: "Wow! It looks like Arizona!" I hadn't been to Arizona yet at that time, but I had seen pictures and my reaction was: "Shouldn't there be some cactus there somewhere?"

I heard an interesting story while an undergraduate student at Cornell which was indicative of the times. After Viking, one of Carl Sagan's graduate student's jobs was to go through all of the images of the Martian surface to see if there were any signs of life, such as moss on the rocks. Sagan wanted to know if there might be anything that might be a sign of life on Mars.

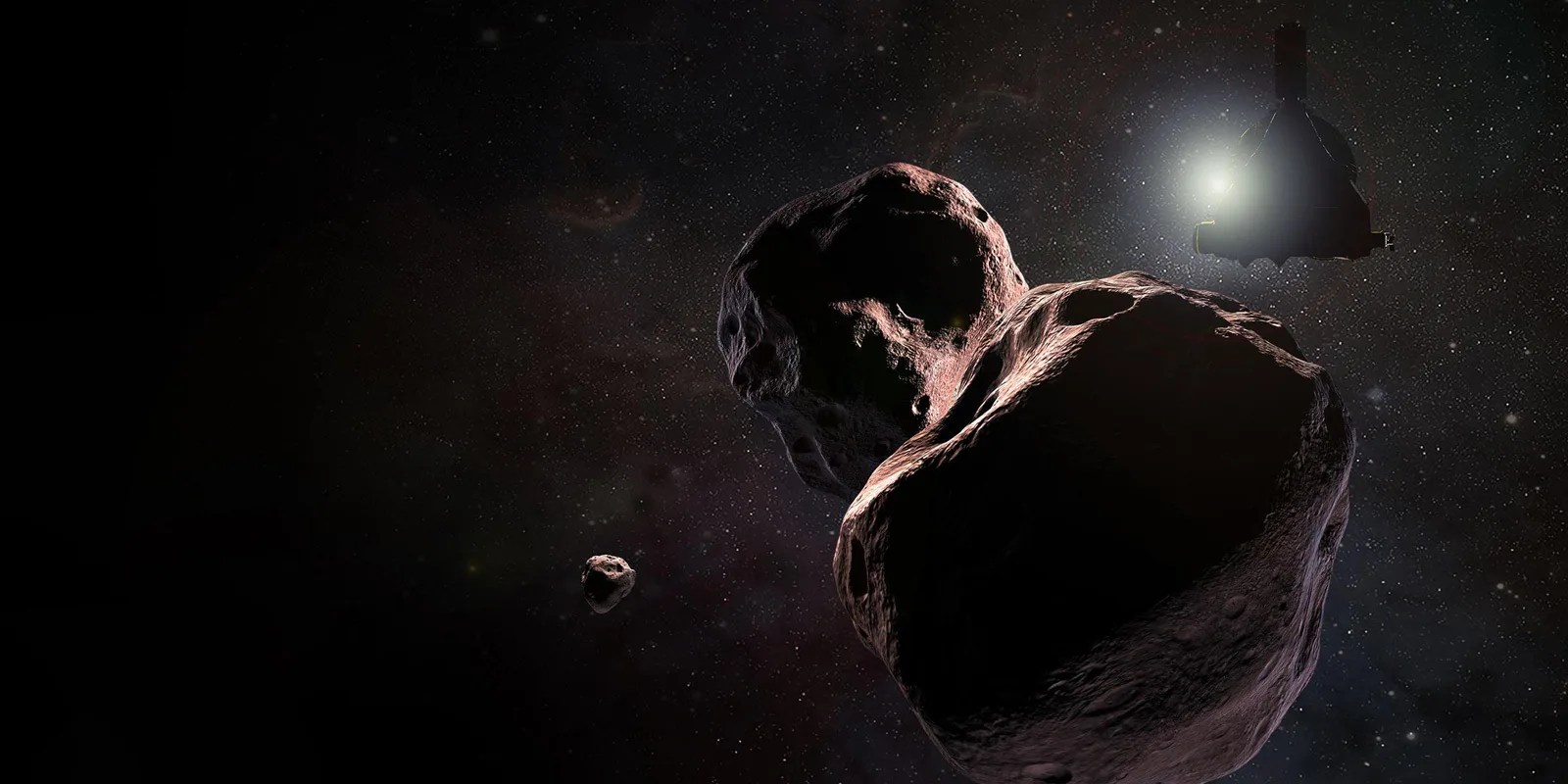

Voyager opened so many doors, so many possibilities -- with so many discoveries. In a broad sense, it let us understand that the outer solar system has been very active in the past -- and presently. So with its grand tour of the solar system, Voyager revolutionized our thinking about icy satellites and how they work and gave us tantalizing clues to so many unique and fascinating worlds.

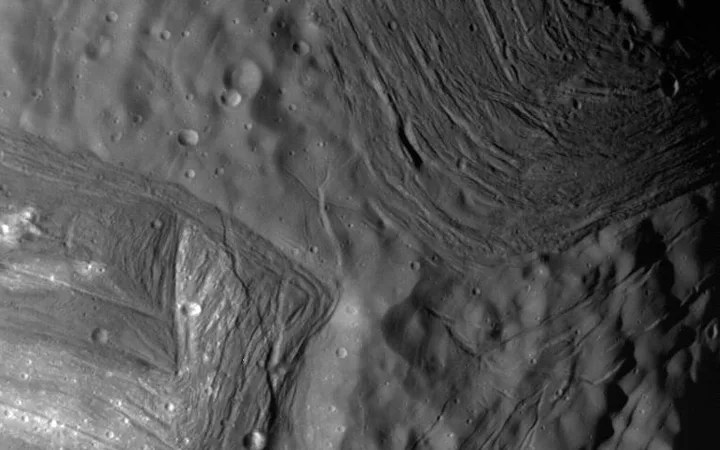

By the time that Voyager arrived at Uranus I was already very interested in icy moons. One particular image taken by Voyager of Uranus' icy moon Miranda fascinates me. It is the image of Miranda's "chevron." This image attests to what Voyager found; in that even a tiny moon like Miranda -- it is only 500 km across, which is about as big as the state of Arizona -- has been geologically active. This was out of the realm of possibility, it seemed, when Voyager was launched. So this image brings us to the outer reaches of the solar system and the bizarre processes there.

And it was just so bizarre when it was seen by the Voyager team at some distance out. "Why does a moon have a giant 'V' on it?" "What's going on here?" This chevron brought up a lot of speculation: "What might form it?" "Did it mean that Miranda was broken apart and reassembled?" We are still not sure what is making that chevron feature. There are some ideas: I suspect that it might be related to spreading of the icy surface on Miranda, which is an idea we didn't really have for icy satellites until we understood Europa better.

It wasn't too long ago I found up in my attic the New York Times article in which the chevron picture appeared back in late January of 1986. Next to the article on Miranda and how fascinating it was, was a column talking about Space Shuttle Challenger. The article spoke about how Challenger was on the launch pad and about how cold it was in Florida at the time. It was just a day or two later that the Challenger disaster happened. Of course, no longer were Uranian satellites on anyone's mind. It is interesting and sad to think about how the press did not and could not follow up much on Voyager's discoveries at Miranda at that time.

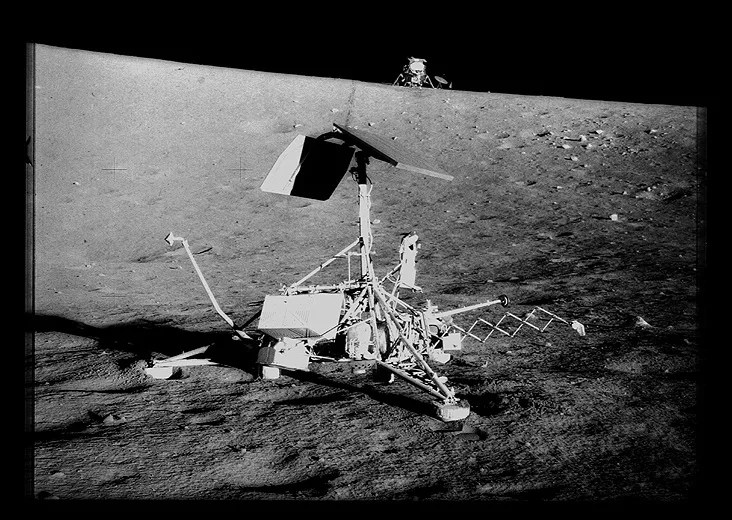

I want to be sure that people don't leave the Moon off their list of significant events -- Apollo is so important!

The Surveyor picture is just fascinating, because hiding in the background there, back in the distance, so that you barely can notice it is the Apollo 12 lunar lander on the surface. It is amazing that we went to a place where we had sent robotic spacecraft earlier, and also that astronauts examined the Surveyor spacecraft and brought back pieces of the spacecraft back to Earth.

There is something retro about the look of the Surveyor -- now even the Apollo lander looks retro to us. This is iconic of the history of exploration -- Surveyor, Apollo and the contrast to where we have progressed to today. Of course, back then we thought that we would be sending astronauts everywhere by this time. So in a sense it is a bit wistful too.

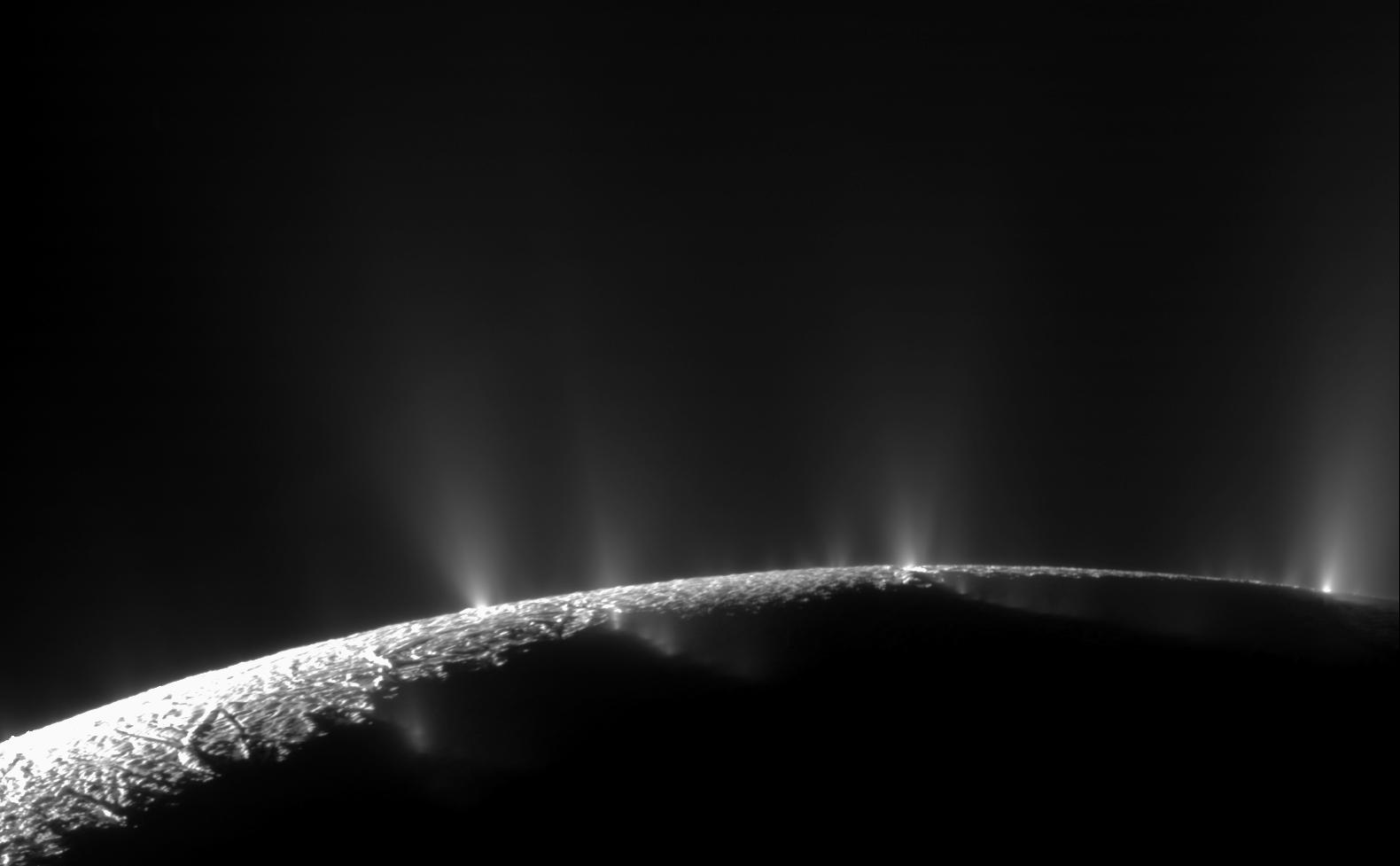

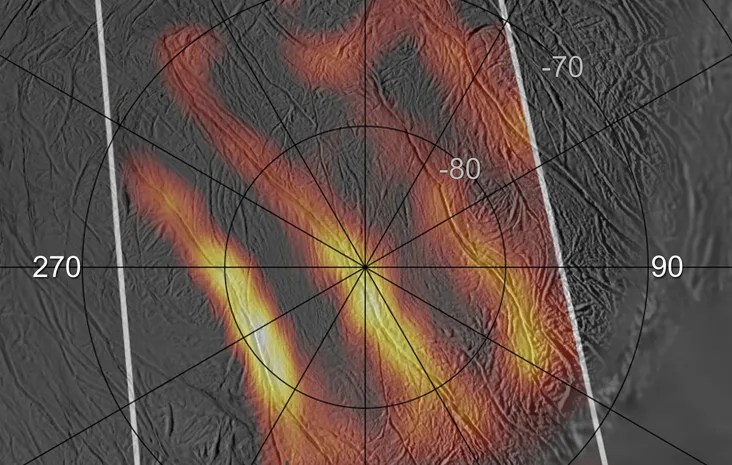

The thermal result of Enceladus. The fact that Enceladus is active and so hot is an amazing advance in the study of planetary satellites. It really forces us to stretch our thinking about how these objects work. Also, the fact that oceans are now thought to be commonplace in large icy satellites and may exist in even small ones like Enceladus is just amazing.

Also, grooved terrain on Ganymede is fascinating to me. It is an analog for tectonic processes that occur on Earth known as rifting. This analog is just beautifully exposed out there on the surface of Ganymede -- a structural geologist's dream. It is really the grooved terrain of Ganymede that hooked me on the study of outer planet satellites back when I was an undergraduate student at Cornell.

Outer planet satellites continue to fascinate me.

Read More:

People:

Missions:

Planets/Moons:

- Europa's Moon Page

- Mars' Planet Page

- Miranda's Moon Page

- Earth's Moon Page

- Enceladus' Moon Page

- Ganymede's Moon Page