Growing up in a very small Colorado town, Jennifer Rocca had a fabulous view of the stars through her telescope. For her, as with many kids, space was cool, and she wanted to become an astronaut or an aerospace engineer.

But in an economically depressed town where most didn't attend college, Rocca had few role models. Her high school guidance counselor told her aerospace was not for women.

She didn't want him to be right.

Today, Rocca is a JPL systems engineer playing a crucial role in the launch of the Dawn mission, scheduled for a June lift-off. As the launch phase lead engineer, she is heading a team of 50 that will monitor the spacecraft during its final hours on Earth and first hours in space.

"We'll be on pins and needles after launch," she says. "The transition from a spacecraft on the launch pad to one in space is very tricky. We'll be taking baby steps with the spacecraft for the first 24 hours."

Overseeing the launch phase requires a precise knowledge of how the spacecraft works. The team is conducting several drills of launch day to ensure that everyone is well rehearsed on what to expect. Rocca has created a step-by-step, four-inch-thick manual of what should happen and when, and what to do if one small step does not go according to plan.

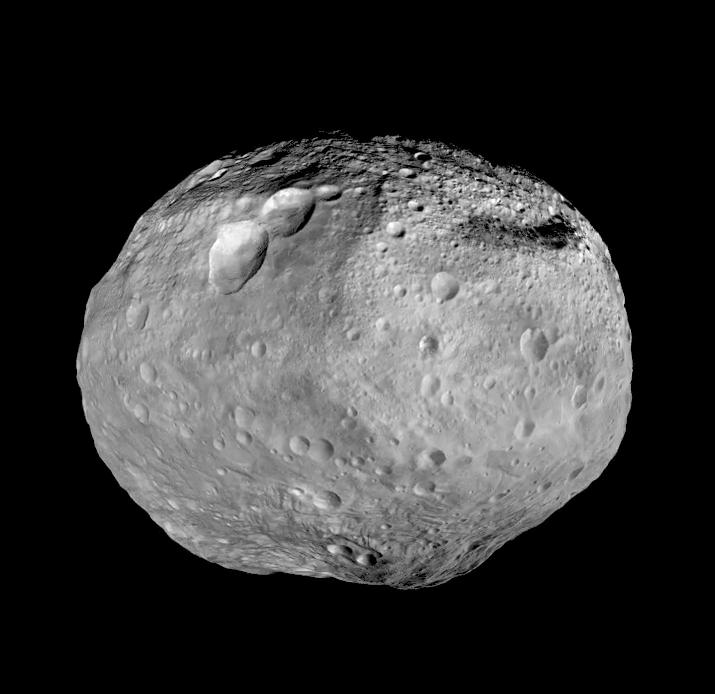

Dawn will be the first spacecraft to travel to and orbit two bodies – Vesta and Ceres, both residents of the asteroid belt. Scientists want to examine asteroids to unravel clues about the origins of our solar system. Ceres has a special appeal since it is the largest member of the belt, which lies between Mars and Jupiter.

The Dawn launch won't be Rocca's first encounter with pressure at JPL. She was part of the 2005 Deep Impact mission, in which the spacecraft's impactor was essentially "run over" by the nucleus of comet Tempel 1. Rocca built the mission's single largest sequence, which coordinated final approach maneuvers and imaging by both spacecraft in the final week prior to encounter.

She and her colleagues worked for 18 months under intense pressure. "Seeing the images come down was an intense relief and joy. We could see directly the payoff of our engineering for the scientists."

Rocca's first important role on a NASA mission was with the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (Grace) twin Earth-orbiting satellites. She was sent to Germany for two years to oversee installation of the JPL-built instruments. Sixteen-hour days were the norm, but she got lots of hands-on hardware experience and time in the cleanroom, where the spacecraft were assembled.

Before coming to JPL in 2000, Rocca earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Aerospace Engineering Sciences from the University of Colorado in Boulder (1998), and a Master of Science degree in Aerospace and Astronautics at Stanford University (2000). Partly because of her own experiences growing up, Rocca believes it's important to meet with young people and share the excitement and realities of a career involving space.

For young women considering an engineering degree, Rocca notes, "The ratio of men to women is getting a lot better, but it's not easy. If you're in a room of 60 students, and there are four women, you can bet you won't be anonymous. The professor is going to know your name."

With an eye to her own future, Rocca regularly updates her application for NASA's astronaut program. As for that guidance counselor back in high school, she makes a point of staying in touch and reminding him that aerospace is indeed a field for women.