1. Explorer 1: The First U.S. Science Robot

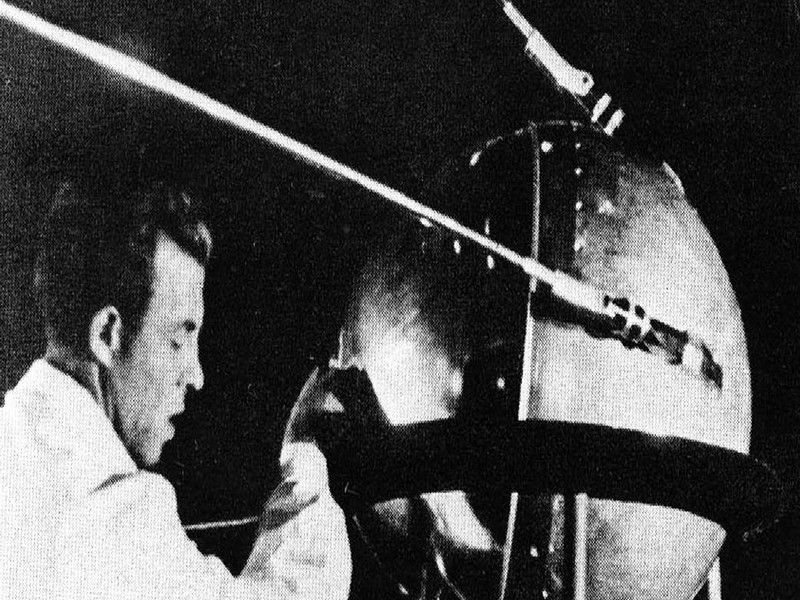

On Jan. 31, 1958, the United States sent Explorer 1, its first satellite, into space. The spacecraft was small enough to be held triumphantly overhead. It orbited Earth from as far as 1,594 miles (2,565 km) above, and made the first U.S. scientific discovery in space.

2. Why It’s Important

The world had changed three months before Explorer 1’s launch, when the Soviet Union lofted Sputnik into orbit on Oct. 4, 1957. That satellite was followed a month later by a second Sputnik spacecraft. All of the missions were inspired when an international council of scientists called for satellites to be placed in Earth orbit in the pursuit of science. The Space Age was on.

3. It … Wasn’t Easy

When Explorer 1 launched, NASA didn’t yet exist. It was a project of the U.S. Army and was built by Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. After the Sputnik launch, the Army, Navy and Air Force were tasked by Pres. Eisenhower with getting a satellite into orbit within 90 days. The Navy’s Vanguard Rocket, the first choice, exploded on the launch pad Dec. 6, 1957.

4. The People Behind Explorer 1

University of Iowa physicist James Van Allen, whose proposal was chosen for the Vanguard satellite, had made sure his scientific instrument – a cosmic ray detector – would fit either launch vehicle. Wernher von Braun, working with the Army Ballistic Missile Agency in Alabama, directed the design of the Redstone Jupiter-C launch rocket, while JPL Director William Pickering oversaw the design of Explorer 1 and other upper stages of the rocket. JPL was also responsible for sending and receiving communications from the spacecraft.

5. All About the Science

Explorer 1’s science payload took up 37.25 inches (95 cm) of the satellite’s total 80.75 inches (2.05 meters). The main instruments were a cosmic-ray detector; internal, external and nose-cone temperature sensors; a micrometeorite impact microphone; a ring of micrometeorite erosion gauges; and two transmitters. There were two antennas in the body of the satellite and its four flexible whips formed a turnstile antenna that extended with the rotation of the satellite. Electrical power was provided by batteries that made up 40 percent of the total payload weight.

6. At the Center of a Space Doughnut

The first U.S. scientific discovery in space came from Explorer 1. Earth is surrounded by radiation belts of electrons and charged particles, some of them moving at nearly the speed of light, about 186,000 miles (299,000 km) per second. The two belts are shaped like giant doughnuts with Earth at the center. Data from Explorer 1 and Explorer 3 (launched March 26, 1958) led to the discovery of the inner radiation belt, while Pioneer 3 (Dec. 6, 1958) and Explorer IV (July 26, 1958) provided additional data, leading to the discovery of the outer radiation belt. The radiation belts can be hazardous for spacecraft, but they also protect the planet from harmful particles and energy from the Sun.

Today, these belts are known as the Van Allen Belts. Two NASA spacecraft, the Van Allen Probes, explored this region from Aug. 30, 2012 to Oct. 18, 2019.

7. 58,376 Orbits

Explorer 1’s last transmission was received May 21, 1958. The spacecraft re-entered Earth's atmosphere and burned up on March 31, 1970, after 58,376 orbits. From 1958 on, more than 100 spacecraft would fall under the Explorer designation.

8. Find Out More!

Want to know more about Explorer 1? Check out the website and download the poster celebrating 60 years of space science. go.nasa.gov/Explorer1

9. Hold the Spacecraft In Your Hands

Create your own iconic Explorer 1 photo (or re-create the original), with our Spacecraft 3D app: https://go.nasa.gov/2BmSCWi

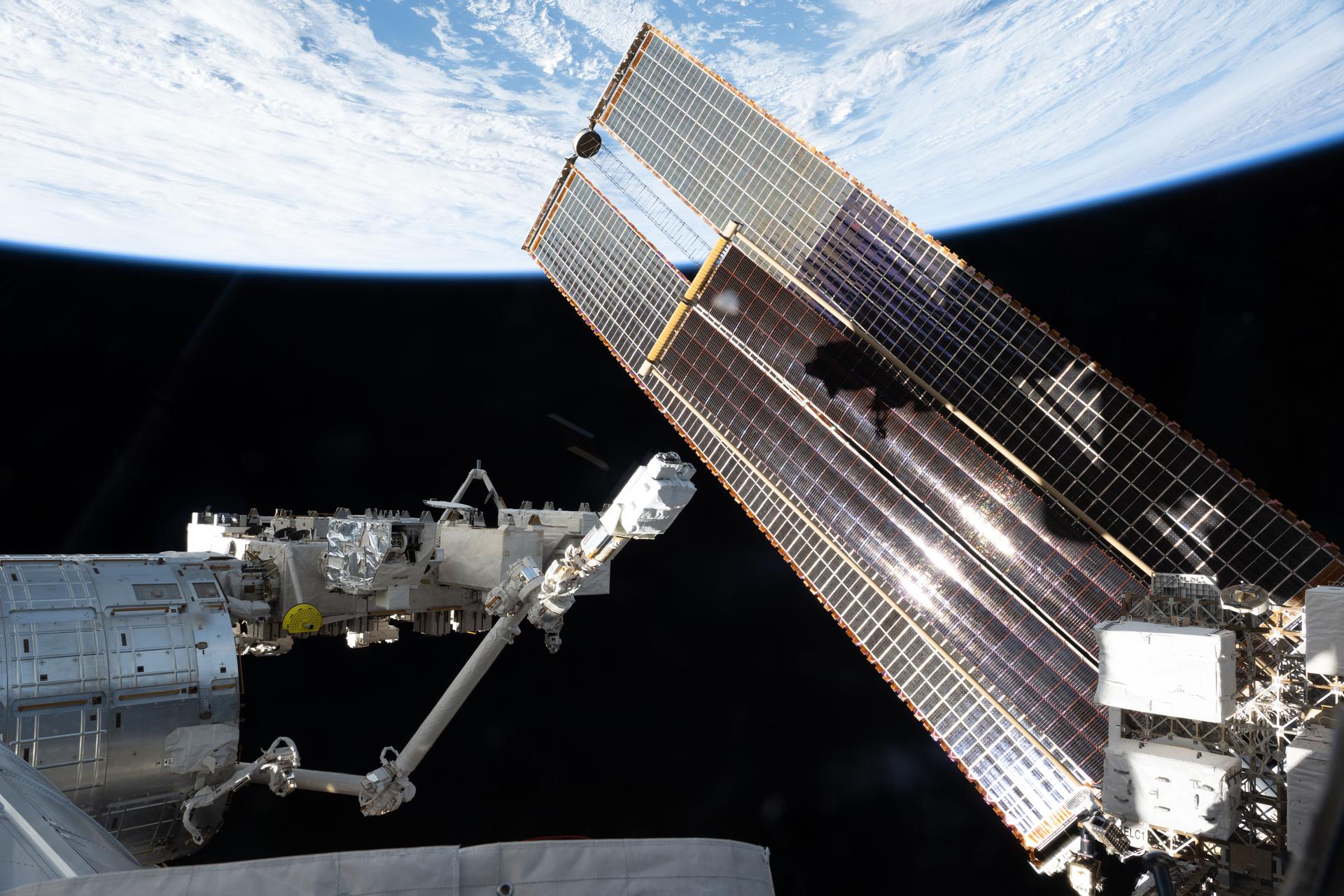

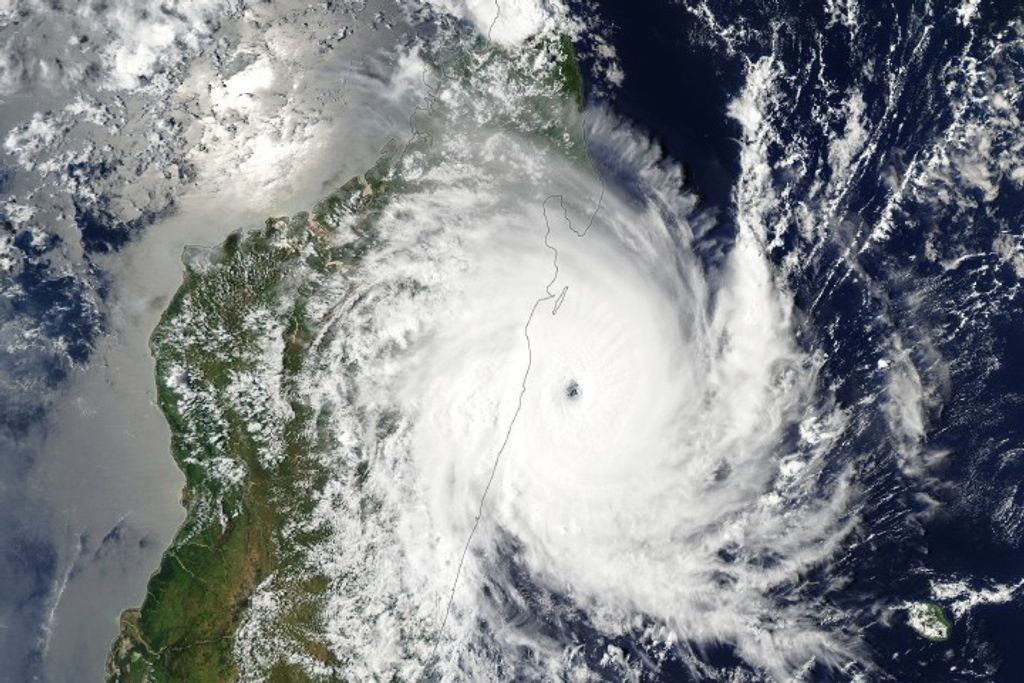

10. What’s Next?

All NASA missions can trace a lineage to Explorer 1, and we keep exploring. In 2024, NASA plans to launch two new Earth climate satellites, and a mission to Europa, one of Jupiter's icy moons.