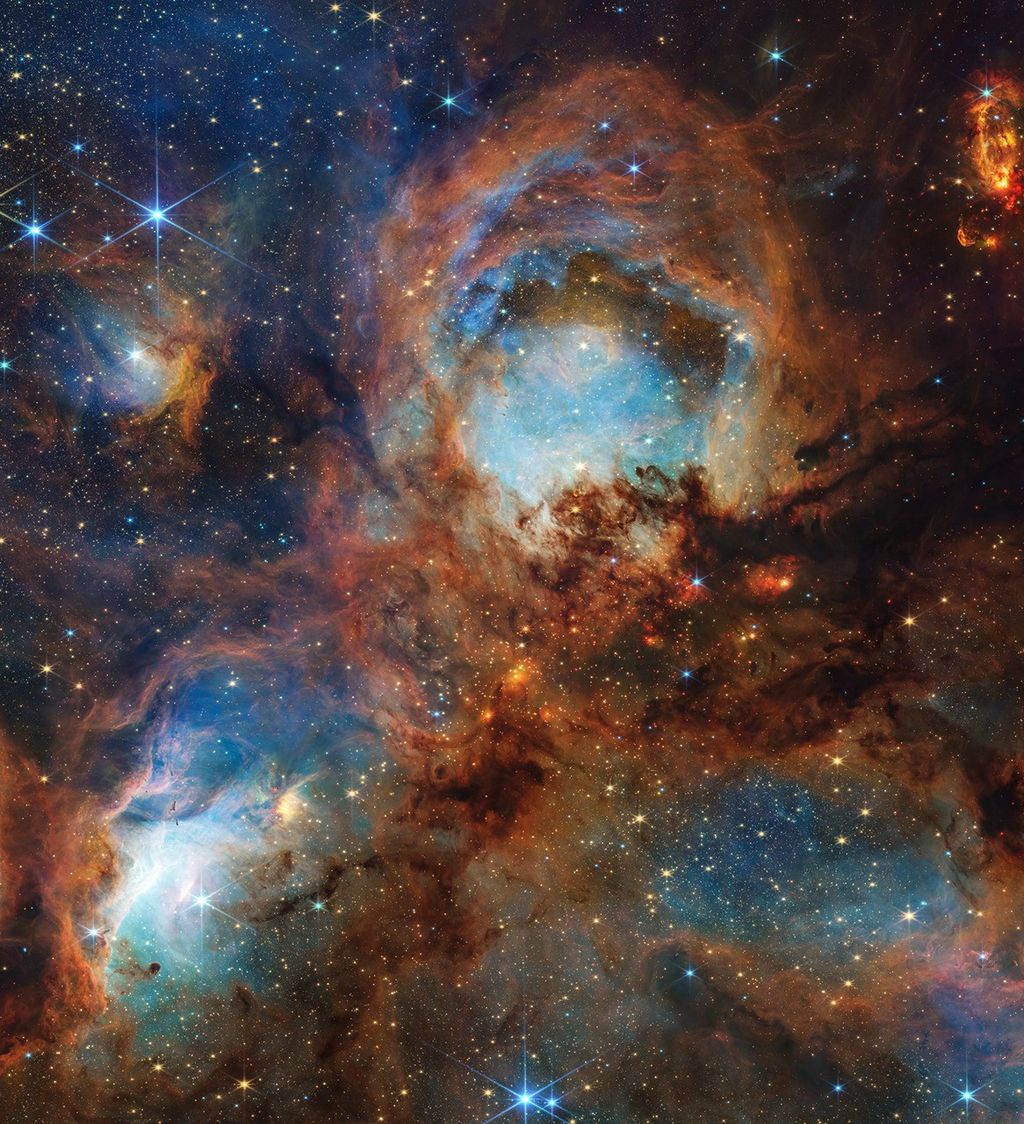

This image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope shows a globular cluster called NGC 1651. Like another recent globular cluster image, NGC 1651 is about 162,000 light-years away in the largest and brightest of the Milky Way’s satellite galaxies, the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC). One notable feature of this image: the roughly 120-light-year diameter globular cluster nearly fills the entire frame. In contrast, other Hubble images feature entire galaxies – which can be tens or hundreds of millions of light-years in diameter – that also more or less fill the whole image.

A common misconception is that Hubble and other large telescopes observe wildly differently sized celestial objects by zooming in on them, as one would with a specialized camera here on Earth. While small telescopes might have the option to zoom in and out to a certain extent, large telescopes do not. Each telescope’s instrument has a fixed ‘field of view’ (the size of the region of sky that it can observe in a single observation). For example, the ultraviolet/visible light channel of Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3), the channel and instrument that collected the data used in this image, has a field of view roughly one twelfth the diameter of the Moon as seen from Earth. When WFC3 makes an observation, its field of view is the size of the region of sky that it can observe.

The reason that Hubble can observe objects of such wildly different sizes is two-fold. First, the distance to an object will determine how big it appears from Earth, so entire galaxies that are relatively far away might take up the same amount of space in the sky as a globular cluster like NGC 1651 that is relatively close by. In fact, there's a distant spiral galaxy lurking in this image, directly left of the cluster – though undoubtedly much larger than this star cluster, it appears small enough here to blend in with foreground stars! Secondly, images processors can stitch together multiple images spanning different parts of the sky into a mosaic to create a single image of objects that are too big for Hubble’s field of view.

Text credit: European Space Agency (ESA)

Media Contact:

Claire Andreoli

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD

claire.andreoli@nasa.gov