3 min read

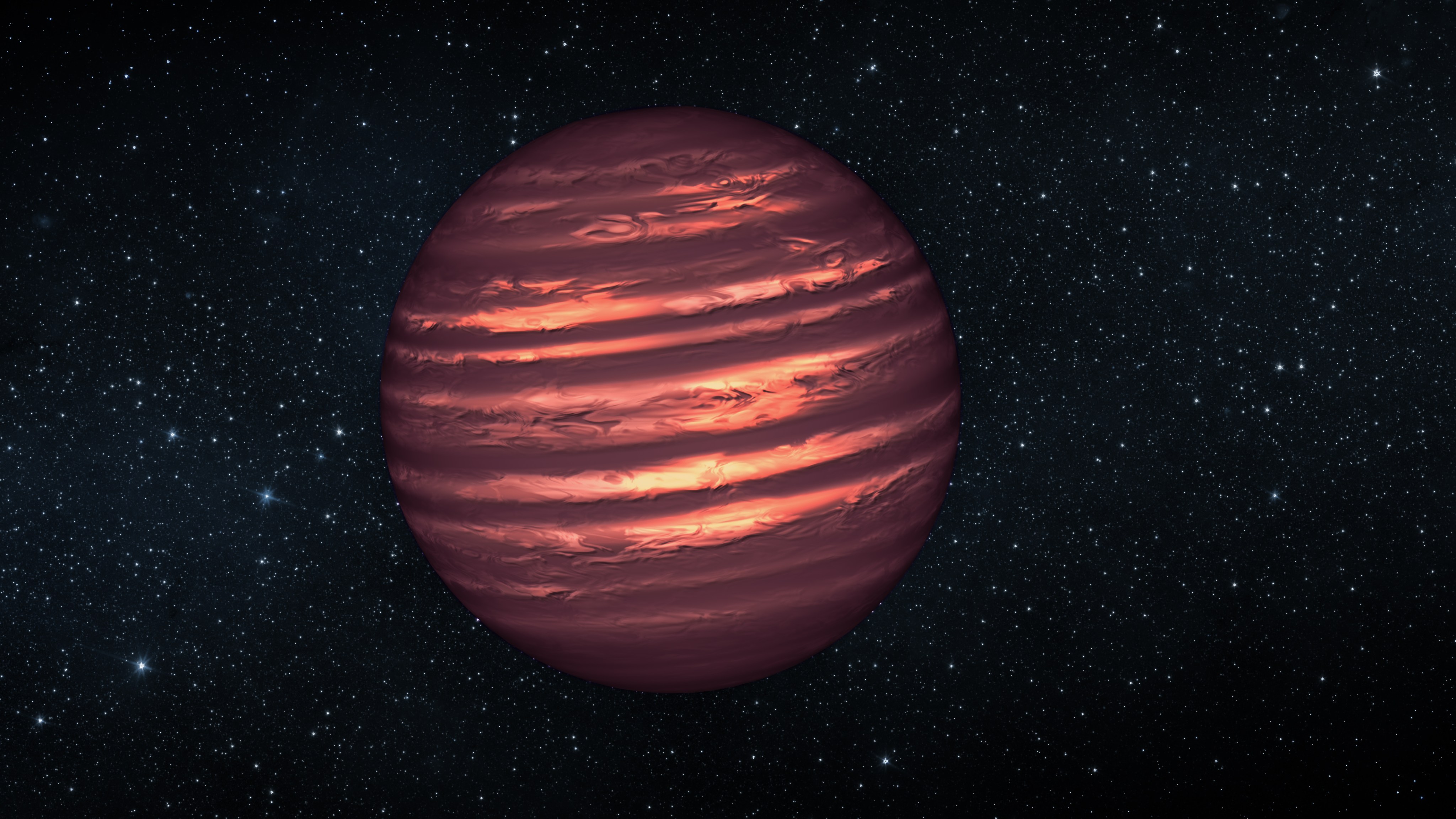

Brown dwarfs form out of condensing gas, as stars do, but lack the mass to fuse hydrogen atoms and produce energy. Instead, these objects, which some call failed stars, are more similar to gas planets with their complex, varied atmospheres. The new research is a stepping stone toward a better understanding not only of brown dwarfs, but also of the atmospheres of planets beyond our solar system.

"With Hubble and Spitzer, we were able to look at different atmospheric layers of a brown dwarf, similar to the way doctors use medical imaging techniques to study the different tissues in your body," said Daniel Apai, the principal investigator of the research at the University of Arizona in Tucson, who presented the results at the American Astronomical Society meeting Tuesday in Long Beach, Calif.

A study describing the results, led by Esther Buenzli, also of the University of Arizona, is published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The researchers turned Hubble and Spitzer simultaneously toward a brown dwarf with the long name of 2MASSJ22282889-431026. They found that its light varied in time, brightening and dimming about every 90 minutes as the body rotated. But more surprising, the team also found the timing of this change in brightness depended on whether they looked using different wavelengths of infrared light.

These variations are the result of different layers or patches of material swirling around the brown dwarf in windy storms as large as Earth itself. Spitzer and Hubble see different atmospheric layers because certain infrared wavelengths are blocked by vapors of water and methane high up, while other infrared wavelengths emerge from much deeper layers.

"Unlike the water clouds of Earth or the ammonia clouds of Jupiter, clouds on brown dwarfs are composed of hot grains of sand, liquid drops of iron, and other exotic compounds," said Mark Marley, research scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., and co-author of the paper. "So this large atmospheric disturbance found by Spitzer and Hubble gives a new meaning to the concept of extreme weather."

According to Buenzli, this is the first time researchers can probe variability at several different altitudes at the same time in the atmosphere of a brown dwarf. "Although brown dwarfs are cool relative to other stars, they are actually hot by earthly standards. This particular object is about 1,100 to 1,300 degrees Fahrenheit (600 to 700 degrees Celsius)," Buenzli said.

"What we see here is evidence for massive, organized cloud systems, perhaps akin to giant versions of the Great Red Spot on Jupiter," said Adam Showman, a theorist at the University of Arizona involved in the research. "These out-of-sync light variations provide a fingerprint of how the brown dwarf's weather systems stack up vertically. The data suggest regions on the brown dwarf where the weather is cloudy and rich in silicate vapor deep in the atmosphere coincide with balmier, drier conditions at higher altitudes – and vice versa."

Researchers plan to look at the atmospheres of dozens of additional nearby brown dwarfs using both Spitzer and Hubble.

"From studies such as this we will learn much about this important class of objects, whose mass falls between that of stars and Jupiter-sized planets." said Glenn Wahlgren, Spitzer Program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "This technique will see extensive use when we are able to image individual exoplanets."