In a nod to the global amateur astronomy community, as well as to any space enthusiast who enjoys the beauty of the cosmos, the Hubble Space Telescope mission is releasing its version of the popular Messier catalog, featuring some of Hubble’s best images of these celestial objects that were once noted for looking like comets but turned out not to be. This release coincides with the Orionid meteor shower — a spectacle that occurs each year when Earth flies through a debris field left behind by Halley’s Comet when it last visited the inner solar system in 1986. The shower will peak during the pre-dawn hours this Saturday, Oct. 21.

Spotting comets was all the rage in the middle of the 18th century, and at the forefront of the comet hunt was a young French astronomer named Charles Messier. In 1774, in an effort to help fellow comet seekers steer clear of astronomical objects that were not comets (something that frustrated his own search for these elusive entities), Messier published the first version of his “Catalog of Nebulae and Star Clusters,” a collection of celestial objects that weren’t comets and should be avoided. Today, rather than avoiding these objects, many amateur astronomers actively seek them out as interesting targets to observe with backyard telescopes, binoculars or sometimes even with the naked eye.

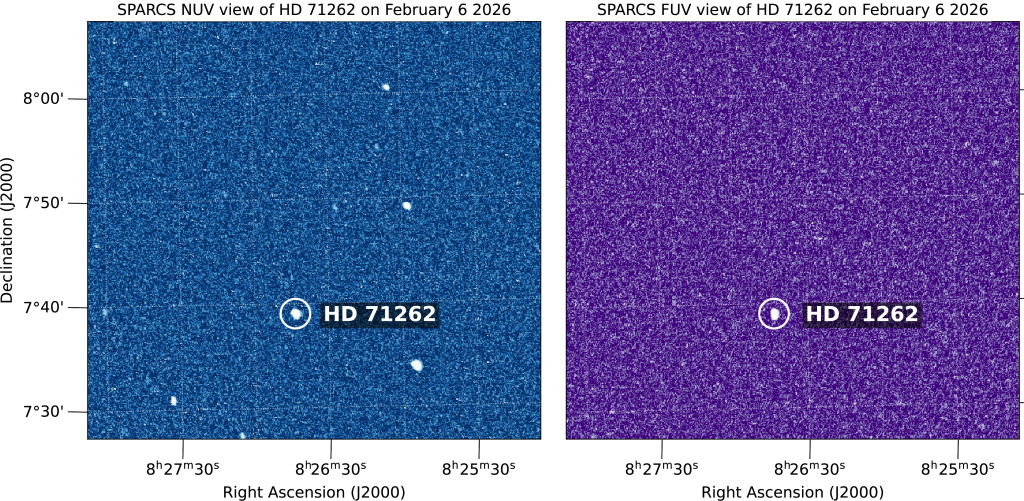

Hubble’s version of the Messier catalog includes eight newly processed images never before released by NASA. The images were extracted from more than 1.3 million observations that now reside in the Hubble data archive. Some of these images represent the first Hubble views of the objects, while others include newer, higher resolution images taken with Hubble’s latest cameras.

While the Hubble Space Telescope has not captured images of all 110 objects in the Messier catalog, it has targeted 93 of them as of September 2017. Some Messier objects have not earned enough scientific interest to warrant Hubble’s time, which is in extremely high demand, or can be studied nearly as well with ground-based research telescopes. Others appear too large in the sky to be observed completely by Hubble, which provides high-resolution views that cover tiny portions of the sky. So while a number of Hubble’s photographs capture a given object in its entirety, many images focus on smaller, more specific areas of interest.

In some cases, Hubble observed a Messier object but didn’t take a picture. Rather, it obtained spectra, which break up an object’s light into its component wavelengths to reveal characteristics such as the object’s chemical composition, velocity and temperature. Hubble’s spectral observations are not included in this photographic catalog.

The gallery currently includes 63 Messier objects and will be updated as more of Hubble’s images are processed. For those objects already in the catalog, amateur astronomers can compare their own sightings with those of Hubble. For skywatchers looking for meteors left by the debris of Comet Halley, they might take some time to search for objects determined not to be comets yet still quite fascinating, as demonstrated by the breathtaking details of Hubble’s pictures.

Hubble’s Messier catalog can be found online at https://www.nasa.gov/content/goddard/hubble-s-messier-catalog and on Flickr at https://www.flickr.com/photos/nasahubble/sets/72157687169041265/.