Ashwin Vasavada

Project Scientist

Contents

- Education

- Where are you from?

- Describe the first time you made a personal connection with outer space.

- How did you end up working in the space program?

- Who inspired you?

- What is a Project Scientist?

- Tell us about a favorite moment so far in your career.

- What advice would you give to someone who wants to take the same career path as you?

- What do you do for fun?

- If you were talking to a student interested in science and math or engineering, what advice would you give them?

- Read More

- Where are they from?

Education

Amos Alonzo Stagg High School, Stockton, CA

UCLA

Bachelors, Geophysics and Space Physics

California Institute of Technology

Doctorate, Planetary Science

Where are you from?

I spent my childhood in Stockton, California, a mid-sized town in the agricultural and central part of the state.

Growing up in Stockton gave me a small town experience as a kid, but it also allowed my family to make trips to nearby places, such as San Francisco, Sacramento and Yosemite. Those trips gave me lots of exposure to science, technology and nature. All of these became life-long passions.

Describe the first time you made a personal connection with outer space.

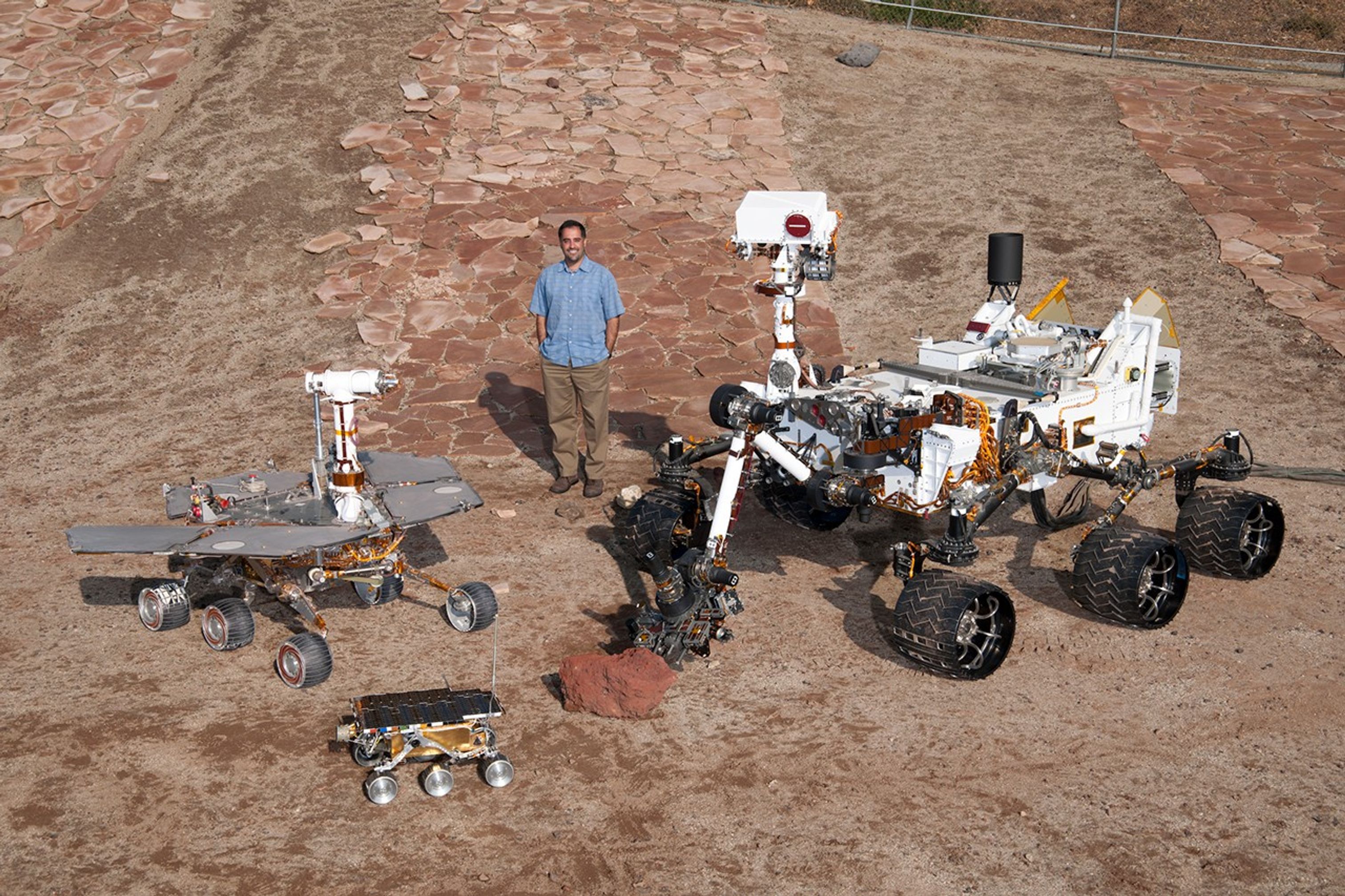

I certainly remember getting interested in outer space through books and television. I especially loved the idea of robotic spacecraft providing glimpses of other worlds — worlds that humans would not have been able to see close-up otherwise.

The Vikings to Mars and the Voyagers to the outer planets both occurred during those years. I would stare at some of the pictures by Viking taken at “eye level” of the surface of Mars and be amazed at how familiar it all looked, yet so incredibly far away. As someone who grew up in the 80s, Star Wars and the space shuttle were also, of course, huge influences. But those two NASA robotic probes were my favorites.

We really are just tiny human beings using all our intellectual and mechanical strength to sling ourselves virtually to other worlds.- Ashwin Vasavada

How did you end up working in the space program?

I took a rather winding road, not because I didn’t have a goal, but because I didn’t know how to get there.

I started at UCLA in aerospace engineering. Aerospace engineering was close to what I was after, but didn’t quite feel right. After learning more about the nature of engineering and science, I realized that science was what really interested me. I switched majors twice in college, once to physics, and then to Earth and space science. Although it took me an extra year to graduate, I finally found my path.

Who inspired you?

As funny as it sounds, NASA robots inspired me: Viking and Voyager.

I do remember a breakthrough moment while at UCLA. I saw an advertisement for a class in planetary science to be taught by David Paige, a professor there. I had no idea there was such a field. Taking that class and a few follow-on classes in Earth science set me on the road to everything that has come since.

What is a Project Scientist?

At NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), we conceive, design, build, test, and fly robotic spacecraft that explore the Earth, the solar system and beyond. It’s a fantastic collaboration between scientists, who ask the questions and make measurements to answer them; and engineers, who develop the spacecraft and instruments that provide the means to make those measurements.

Most scientists who work with NASA spacecraft are based at universities and other institutions around the world. However, a few reside at places such as JPL so they can work closely with the engineers, helping to ensure that the spacecraft will be able to best address the scientific questions at the core of its mission. On Curiosity, we have a few hundred scientists involved, but just about a dozen of us are at JPL (of which I am one).

Tell us about a favorite moment so far in your career.

Two come to mind.

One was in 1995, when Galileo arrived at Jupiter. It was my first time working as part of a science team on a NASA mission. We had planned to take some images of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot (a large storm). The images arrived overnight, and I came in early to look at them. All of a sudden, it hit me that here I was in this dark student lab, in the second sub-basement of Caltech, looking at a vista of Jupiter that no other human had laid eyes on before. Suddenly I was an explorer, like those who had inspired me before.

A more recent moment was in 2011, when Curiosity launched on its way to Mars. I had worked on the mission for seven years, mostly through an unimaginable number of documents and dry meetings. But seeing our car-sized rover look so tiny on top of a massive rocket, and then seeing that rocket take our baby away from Earth in a roar of thunder and fire, it became much more real. We really are just tiny human beings using all our intellectual and mechanical strength to sling ourselves virtually to other worlds.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to take the same career path as you?

Find your passion and then follow it. While this may sound cliché, it is quite important advice.

There are ways to make money and get powerful and rich. Science isn’t one of them. It takes an enormous amount of dedication and sacrifice compared with other careers, and the tangible rewards aren’t always clear. But if you have a passion to understand the world around you, and to create knowledge that will become part of human history, science becomes its own reward.

What do you do for fun?

I’ve been a musician my whole life: drums and piano. Although I don’t get to play as much anymore, I do enjoy live music whenever possible. I also love to get out into the desert and mountains. Los Angeles has some incredible scenery within a few hours of driving. Every summer I try to spend a few nights backpacking in the High Sierra.

More related to work, I really enjoy giving talks about Curiosity in classrooms and at other events. I volunteer quite a bit at inner-city schools in Los Angeles too.

If you were talking to a student interested in science and math or engineering, what advice would you give them?

First of all I’d say: That’s wonderful! Take lots of classes so you can learn just what kind of science, math, engineering, or technology really excites you. Then work hard and become a real expert in whatever that is. The class work can be hard and not always seem that fun or relevant, but it will be worth it.

For college students, I’d advise to think long term. Learn the basics of your field very well, even if it means passing up some early job opportunities to further specialize or obtain your dream job.

Read More

Mars Science Laboratory Website

Where are they from?

Planetary science is a global profession.