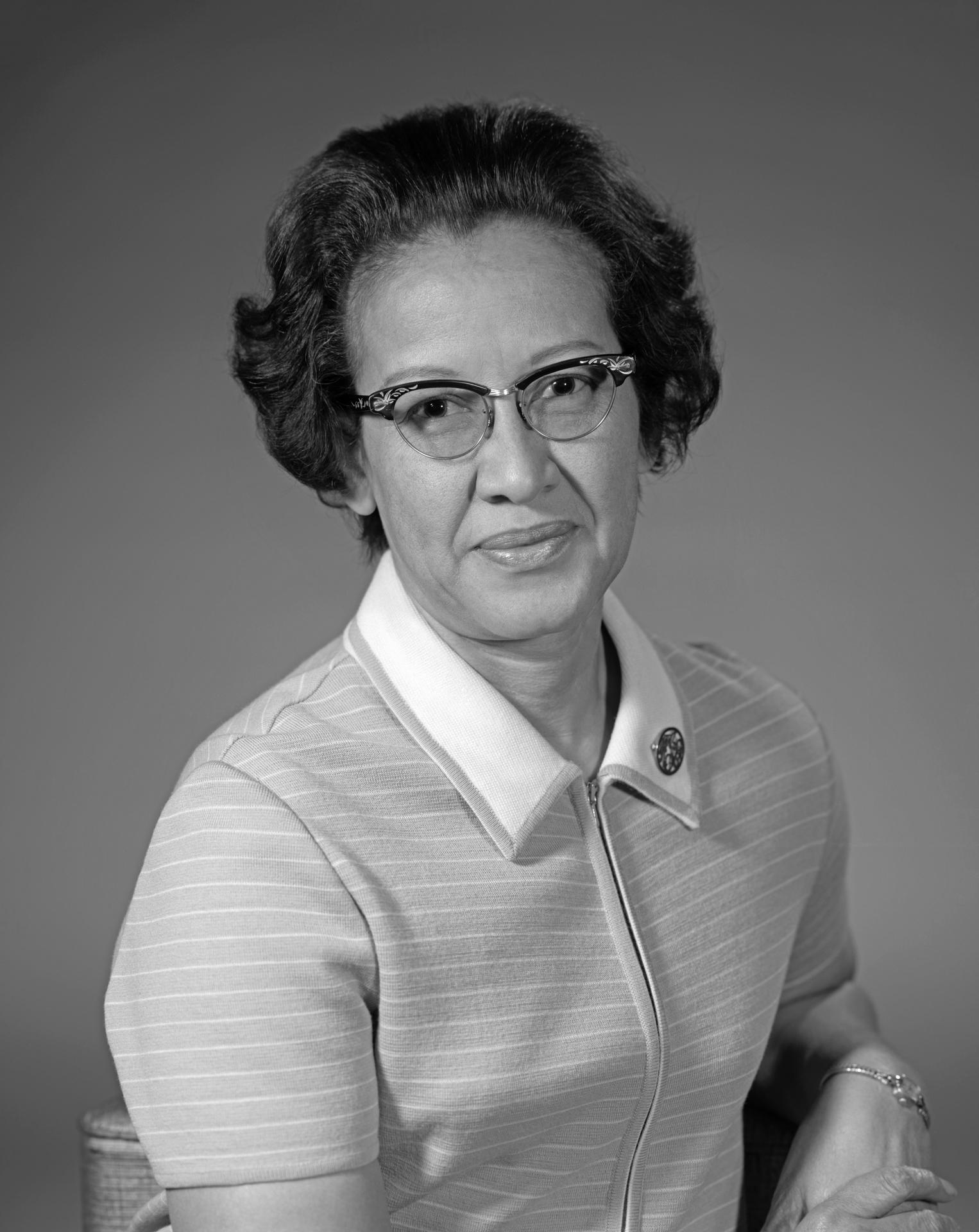

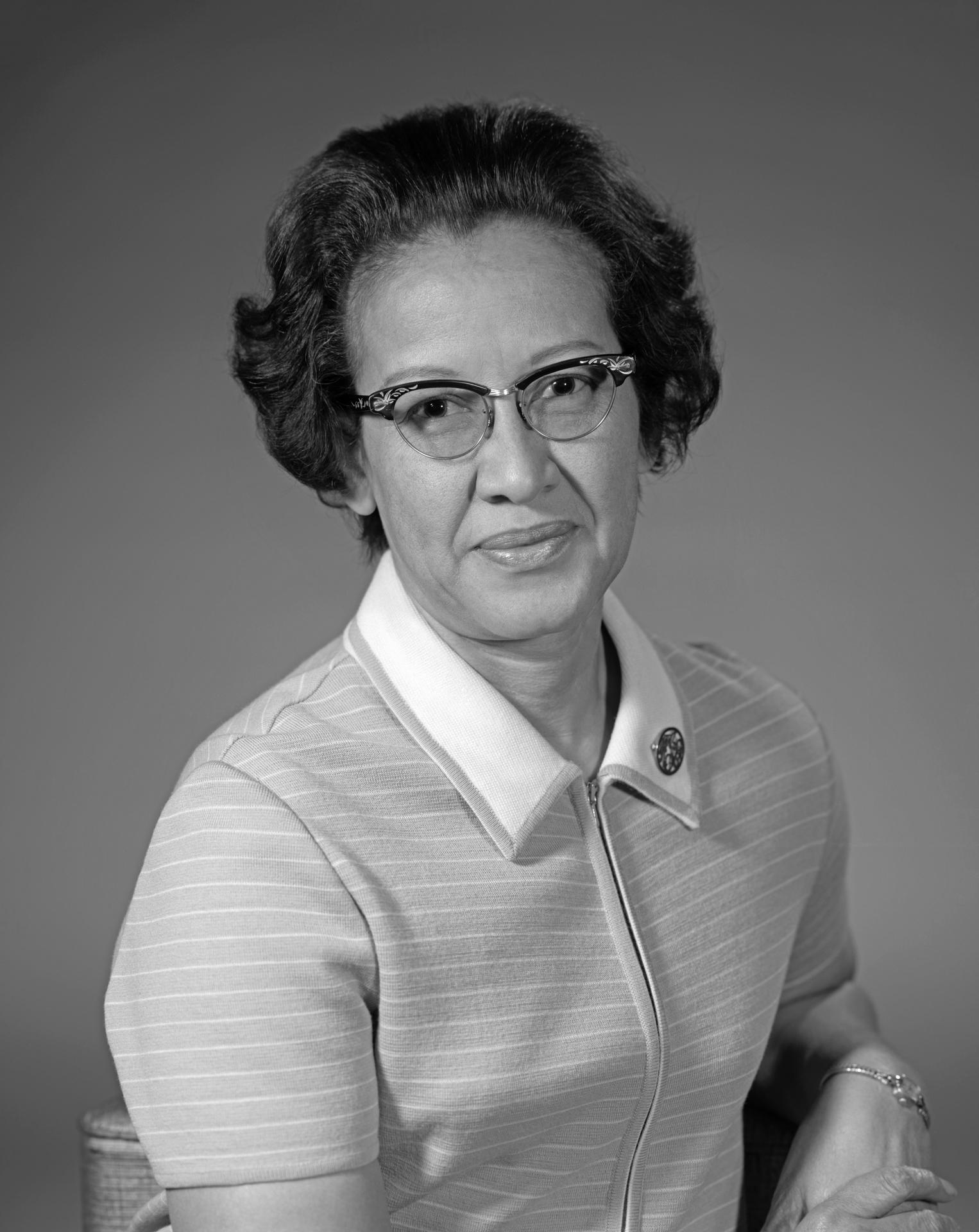

Katherine Johnson (1918-2020)

Former NASA Research Mathematician

Contents

- Education

- What first sparked your interest in space and science?

- How did you end up working for the space program?

- What's one piece of advice you would give to others interested in a similar career?

- What is the key message you want people to take away from your life?

- What was going through your mind at the opening of the Katherine G. Johnson Computational Research Facility?

- How would you feel if the calculations for going to Mars were done in the Katherine Johnson Building?

- Where are they from?

Education

West Virginia State College

B.S., Mathematics and French, 1937

Katherine Johnson was born on August 26, 1918, in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. As a girl, Katherine loved to count. “I counted everything. I counted the steps to the road, the steps up to church, the number of dishes and silverware I washed…anything that could be counted, I did.”

Her father, Joshua Coleman, was determined that his bright little girl would have a chance to meet her potential. He drove his family 120 miles to Institute, West Virginia, where she could continue her education through high school. Katherine’s academic performance proved her father was right: She skipped through grades to graduate from high school at age 14 and college at 18.

From there, she went on to become a well-respected NASA mathematician – a human computer whose calculations helped put American astronauts into space and, ultimately, on the Moon. She was a “computer” at Langley Research Center “when the computer wore a skirt,” Katherine once said.

Astronaut John Glenn, the first American to orbit Earth, famously said of Katherine’s Project Mercury numbers check, “If she says they’re good, then I am ready to go.”

Katherine also was an African American trailblazer. In 2015, President Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom for a pioneering legacy that opened doors for countless women who wanted careers in science and engineering. In 2016, she was portrayed by Taraji P. Henson in the movie “Hidden Figures.” In 2017, NASA Langley Research Center named its new Computational Research Facility in her honor. And in 2019, she was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal.

Katherine died Feb. 24, 2020, at her home in Newport News, Virginia, at the age of 101. This tribute was compiled from interviews and biographies.

She was an American hero and her pioneering legacy will never be forgotten.

Jim Bridenstine

NASA Administrator

What first sparked your interest in space and science?

In college, Katherine’s math skills drew the attention of a young professor, W.W. Schiefflin Claytor. Katherine credits him with inspiring her to become a research mathematician.

He [Claytor] said, “You’d make a good research mathematician and I’m going to see that you’re prepared.”

I said, “Where will I get a job?”

And he said, “That will be your problem.”

And I said, “What do they do?”

And he said, “You’ll find out.”

In the back of my mind, I wanted to be a research mathematician.

How did you end up working for the space program?

[While on vacation from a $100-a-month teaching job in 1952] I heard that Langley was looking for Black women computers.

Katherine was hired at Langley, and about five years later became involved in something called the “Space Task Force.” That was 1958 when the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

We wrote our own textbook because there was no other text about space. We just started from what we knew. We had to go back to geometry and figure all of this stuff out. Inasmuch as I was in at the beginning, I was one of those lucky people.

I found what I was looking for at Langley. This was what a research mathematician did. I went to work every day for 33 years happy. Never did I get up and say I don’t want to go to work.

Do your best. But like it! Like what you do; then you will do your best.

Katherine Johnson

Tell us about your job. What did you do?

As a human computer, Katherine calculated the trajectory for astronaut Alan Shepard’s 1961 Freedom 7 mission to space – the first spaceflight for an American.

Early on, when they said they wanted the capsule to come down at a certain place, they were trying to compute when it should start. I said, “Let me do it. You tell me when you want it and where you want it to land, and I’ll do it backward and tell you when to take off.” That was my forte.

Even after NASA had electronic computers, John Glenn requested that Katherine personally recheck the computer calculations before his 1962 Friendship 7 flight – the first American mission to orbit Earth.

You could do much more, much faster on the computer. But when they went to computers, they called over and said, “Tell her to check and see if the computer trajectory they had calculated was correct.” So I checked it, and it was correct.

Katherine continued to work at NASA until 1986. Her calculations proved critical to the success of the Apollo Moon landings and the start of the Space Shuttle program.

I didn’t do anything alone but try to go to the root of the question – and succeeded there.

The main thing is I liked what I was doing. I liked work. I like the stars and the stories we were telling. And it was a joy to contribute to the literature that was going to be coming out.

But you know, math is the same. If I gave you that answer last year, it’s the same now. It’s the same.

What's one piece of advice you would give to others interested in a similar career?

Do your best. But like it! Like what you do and then you will do your best. If you don’t like it, shame on you.

What is the key message you want people to take away from your life?

If they just did the hard work that I did – which was my job. I did it every day. I never missed a day. Never stayed home playing sick and stuff. My problem was to answer questions, and I did that to the best of my ability at all times – correct or incorrect. But that’s my theory – do your best all the time.

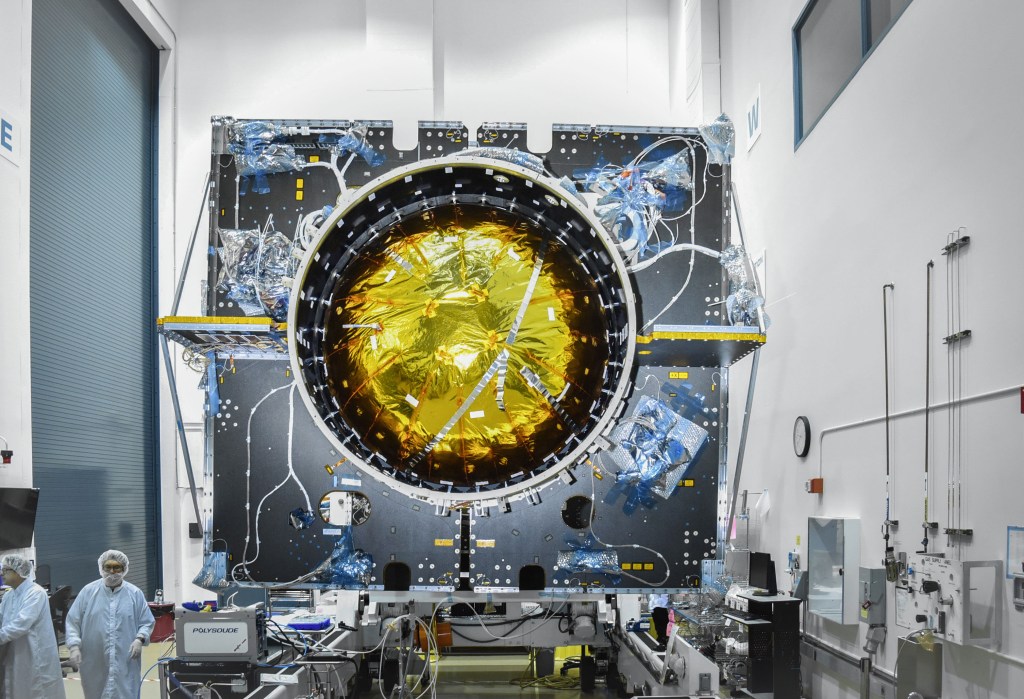

What was going through your mind at the opening of the Katherine G. Johnson Computational Research Facility?

You want my honest answer? I think they’re crazy! [Laughs] I was excited. It was something new. Always like something new. It gives credit to everybody who helped.

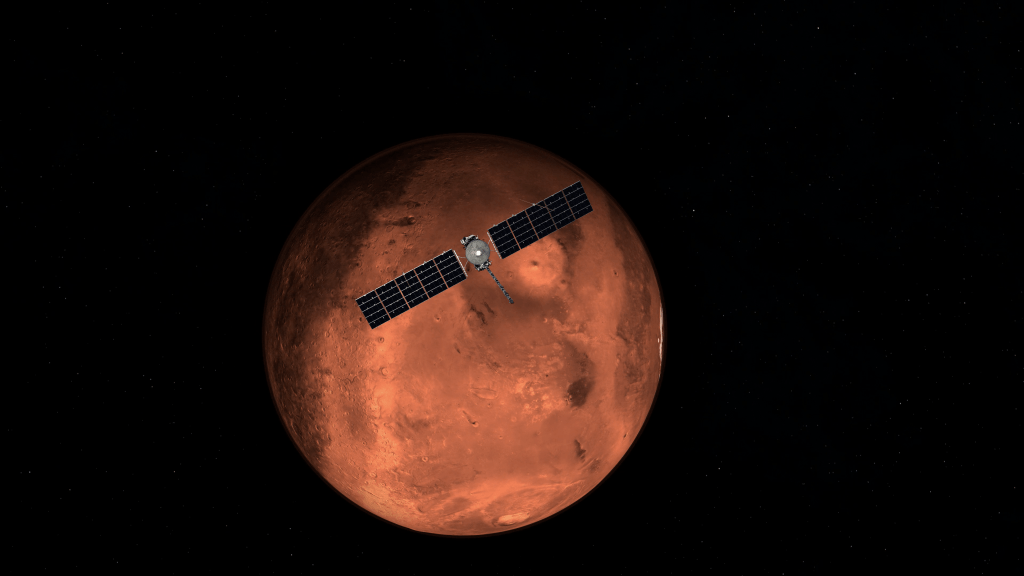

How would you feel if the calculations for going to Mars were done in the Katherine Johnson Building?

I’ll be exceedingly honored, greatly honored.

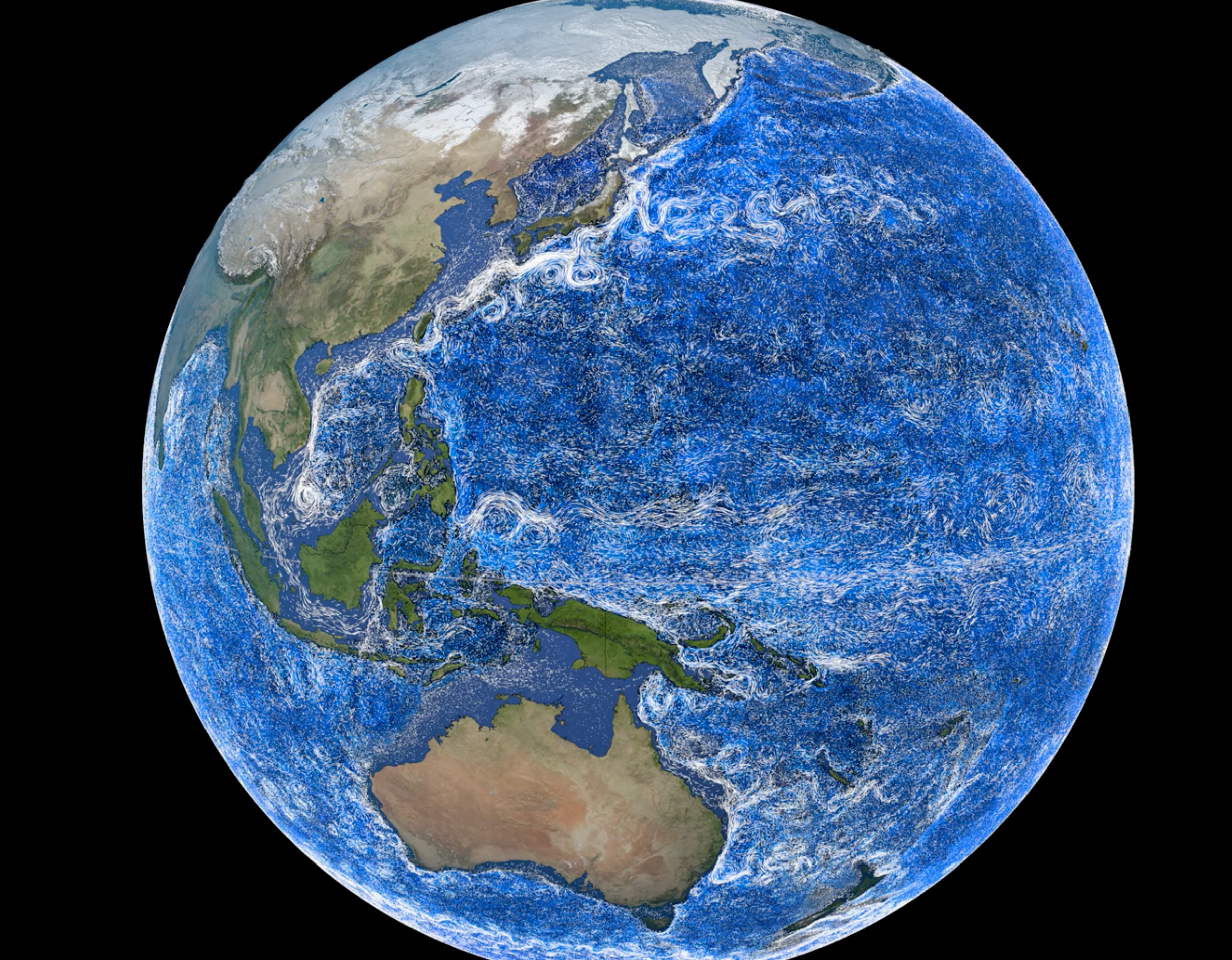

Where are they from?

Planetary science is a global profession.