Qing Liang

Research Physical Scientist, Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory - NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Contents

- Education

- What first sparked your interest in space and science?

- How did you end up in the space program?

- Tell us about your job. What do you do?

- What’s one piece of advice you would give others interested in a similar career?

- Who inspired you?

- Describe a favorite moment so far in your career.

- What do you do for fun?

- What is your favorite space image and why?

- Where are they from?

Education

University of Washington

Ph.D. Atmospheric Sciences

What first sparked your interest in space and science?

My interest in space and science started when I was in elementary school. I was inspired by the Chinese Space Agency’s exciting first satellite launches that we would watch on our 11-inch black-and-white TV and by the stacks of Aerospace Knowledge Magazines my brother owned. Although I went to a special language school, Hangzhou Foreign Language School (HFLS), which was founded to train language experts and diplomats for the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs for middle- and high-school education, I had always dreamed about becoming an engineer or scientist working on space science.

Looking back, my childhood daydreaming probably motivated me to take the very long journey in choosing science over language in college. Later, I traveled across the Pacific Ocean for graduate school education, where I finally got my Ph.D. in Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Washington.

“Always be passionate about what you do. Learn to listen to people, especially those from a different field or discipline.” – Qing Liang

How did you end up in the space program?

My Ph.D. dissertation focused on how polluted air from Asia travels across the Pacific Ocean and influences air quality over the U.S. That was when I recognized the importance of understanding the mixing of air from the upper atmosphere with that in the lower atmosphere for reliable model predictions of surface air quality and for policy implications. Because of that, I joined the NASA Goddard Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory (which has some of the world’s leading scientists on stratospheric research) as a NASA postdoctoral fellow and never left.

Tell us about your job. What do you do?

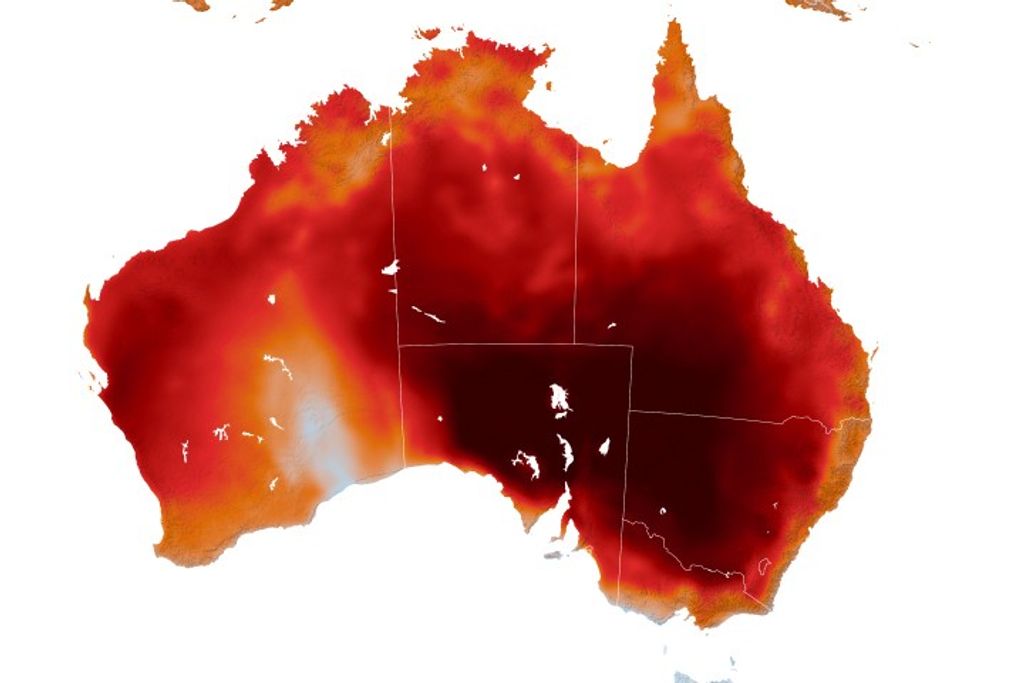

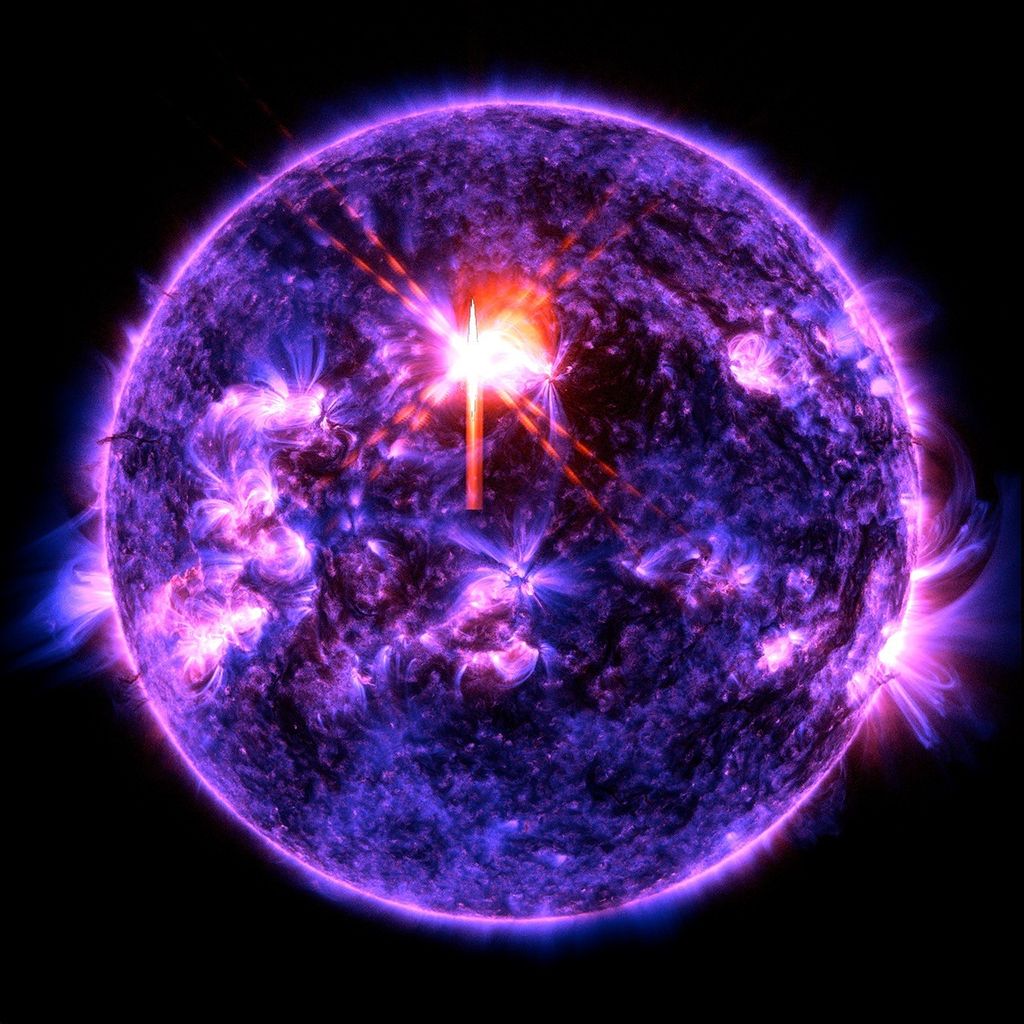

I am an atmospheric chemistry modeler. I use a global three-dimensional chemistry climate model (a simulation of how our global climate and atmospheric composition work interactively) to study how trace gases emitted from natural and human activities get into the atmosphere and change its chemical balance, as well as Earth’s energy balance.

For example, I study human-caused chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which release chlorine atoms that destroy the ozone layer, and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HFCs), which absorb radiation and heat up the atmosphere. I also study how trace gases emitted from human combustion, land vegetation, forest fires, and oceans perturb the atmospheric abundance of the hydroxyl radical, which is a critical cleansing agent in the atmosphere for many gases and particles. As a modeler, I combine my model simulations with measurements from ground-based instruments, aircraft, and satellites to improve our understanding of atmospheric composition and the models that represent it.

Since my graduate school years, I have also been a science team member of several NASA aircraft field missions, and I have worked with many colleagues around the world on a few assessment reports related to atmospheric chemistry. I also serve as a co-lead of the NASA Goddard chemistry-climate model GEOSCCM and work with my Goddard colleagues to use our state-of-the-art model to understand potential feedbacks (processes that either amplify or diminish factors driving our climate) between the atmosphere’s composition and the state of the climate.

What’s one piece of advice you would give others interested in a similar career?

Always be passionate about what you do. Learn to listen to people, especially those from a different field or discipline. I think these are two important qualities that differentiate the great scientists from the rest.

Who inspired you?

Throughout my many years in atmospheric research, I have had the pleasure to work with many great scientists who have inspired me in different ways: my Ph.D. advisor, Prof. Lyatt Jaeglé, who taught me how to think thoroughly; my postdoctoral advisor, Dr. Richard Stolarski, with whom I have enjoyed many inspirational conversations on science; and many others who have had a great impact on me because of their passion for NASA and science.

Of all these influences, I think I have been most inspired by my fellow colleague Dr. Paul Newman. Along with many other colleagues around the world, his devotion to ozone research and his contribution to ratifying the Kigali Amendment in 2016 to phase down climate-warming HFCs in the coming decades made me realize that what we do matters for Earth to become a better planet. (The Kigali Amendment is an agreement under the Montreal Protocol, an international treaty to protect Earth’s ozone layer.)

Describe a favorite moment so far in your career.

My favorite moment in my career was in the field working on flight planning for the NASA INTEX-B (2006) and ARCTAS (2008) aircraft missions. I worked with my colleagues and used the NASA chemistry model to guide where NASA research aircraft should fly to sample interesting air masses – for example, those from forest fires or anthropogenic (human-caused) pollution from Asia or North America. As exhausting as the missions were, those were extremely fun and valuable experiences during which I learned a lot about science, instruments, and more, and also made a lot of good friends.

What do you do for fun?

In my spare time, I like to read, build LEGOs, cook, and bake.

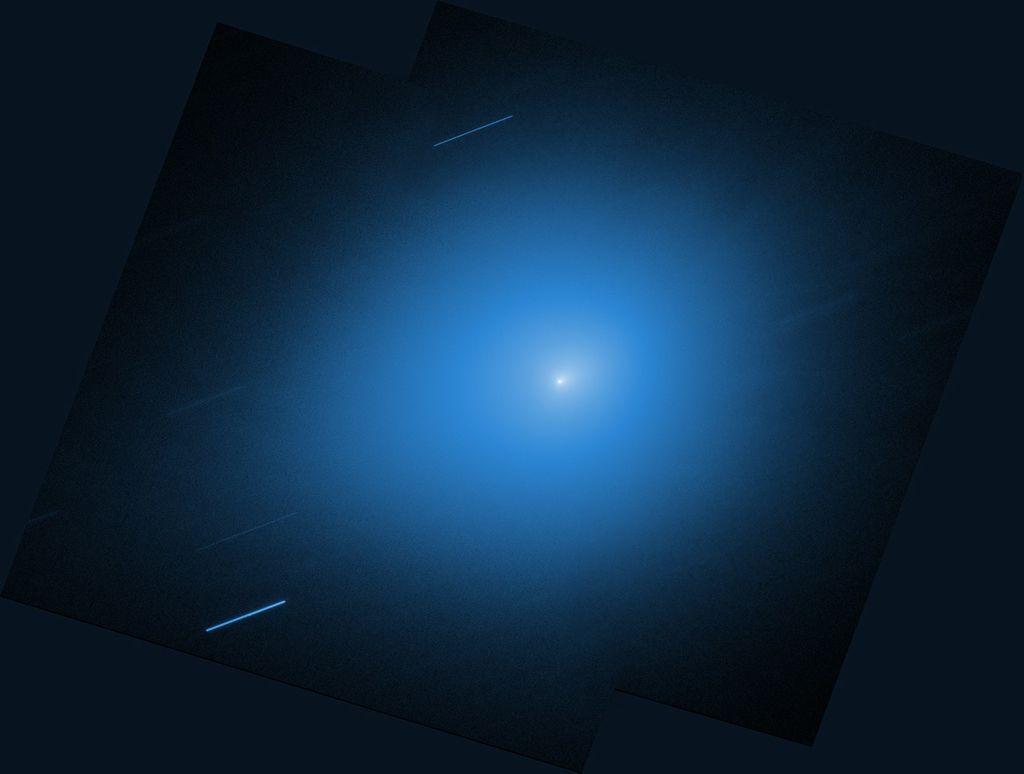

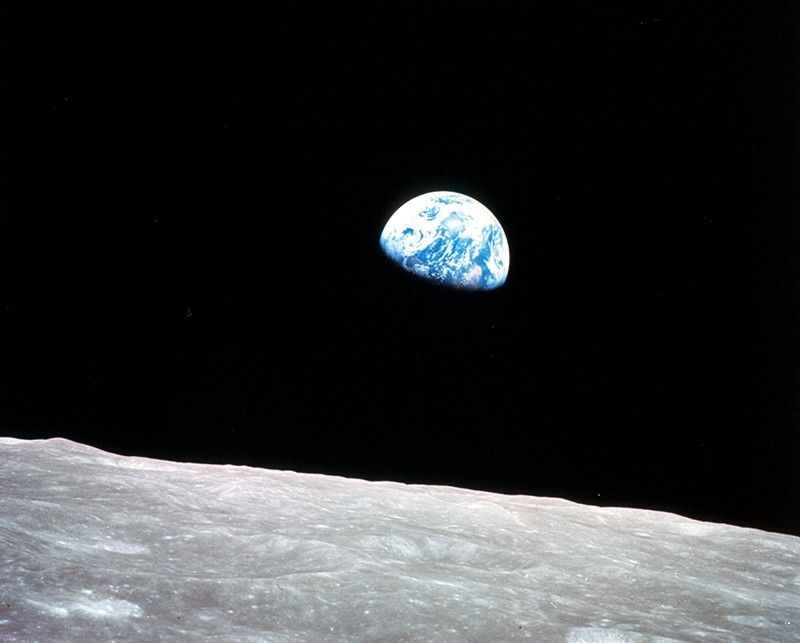

What is your favorite space image and why?

My favorite space image is the image of Earth rising over the Moon from Apollo 8. This picture reminds me to take a step away and look at something from a different angle, and there lie the new findings. Furthermore, this image always makes me wonder what is in the unknown world beyond Earth and the solar system.

Where are they from?

Planetary science is a global profession.