Real Martians: How to Protect Astronauts from Space Radiation on Mars

| Credit | NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center |

|---|---|

| Language |

|

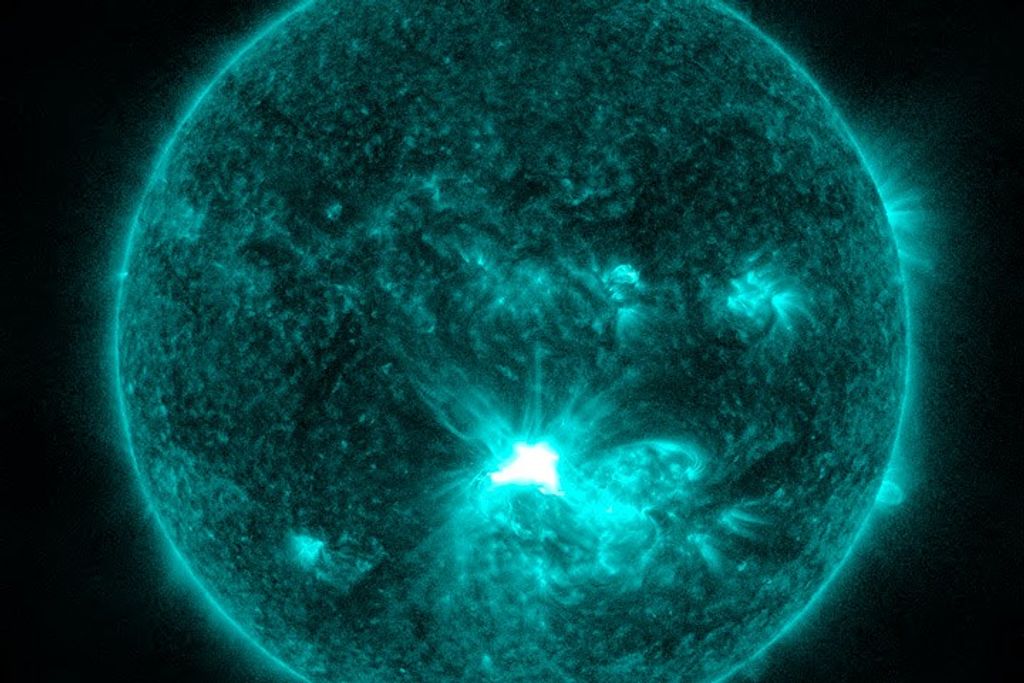

On Aug. 7, 1972, in the heart of the Apollo era, an enormous solar flare exploded from the sun’s atmosphere. Along with a gigantic burst of light in nearly all wavelengths, this event accelerated a wave of energetic particles. Mostly protons, with a few electrons and heavier elements mixed in, this wash of quick-moving particles would have been dangerous to anyone outside Earth’s protective magnetic bubble. Luckily, the Apollo 16 crew had returned to Earth just five months earlier, narrowly escaping this powerful event.

In the early days of human space flight, scientists were only just beginning to understand how events on the sun could affect space, and in turn how that radiation could affect humans and technology. Today, as a result of extensive space radiation research, we have a much better understanding of our space environment, its effects, and the best ways to protect astronauts—all crucial parts of NASA's mission to send humans to Mars.

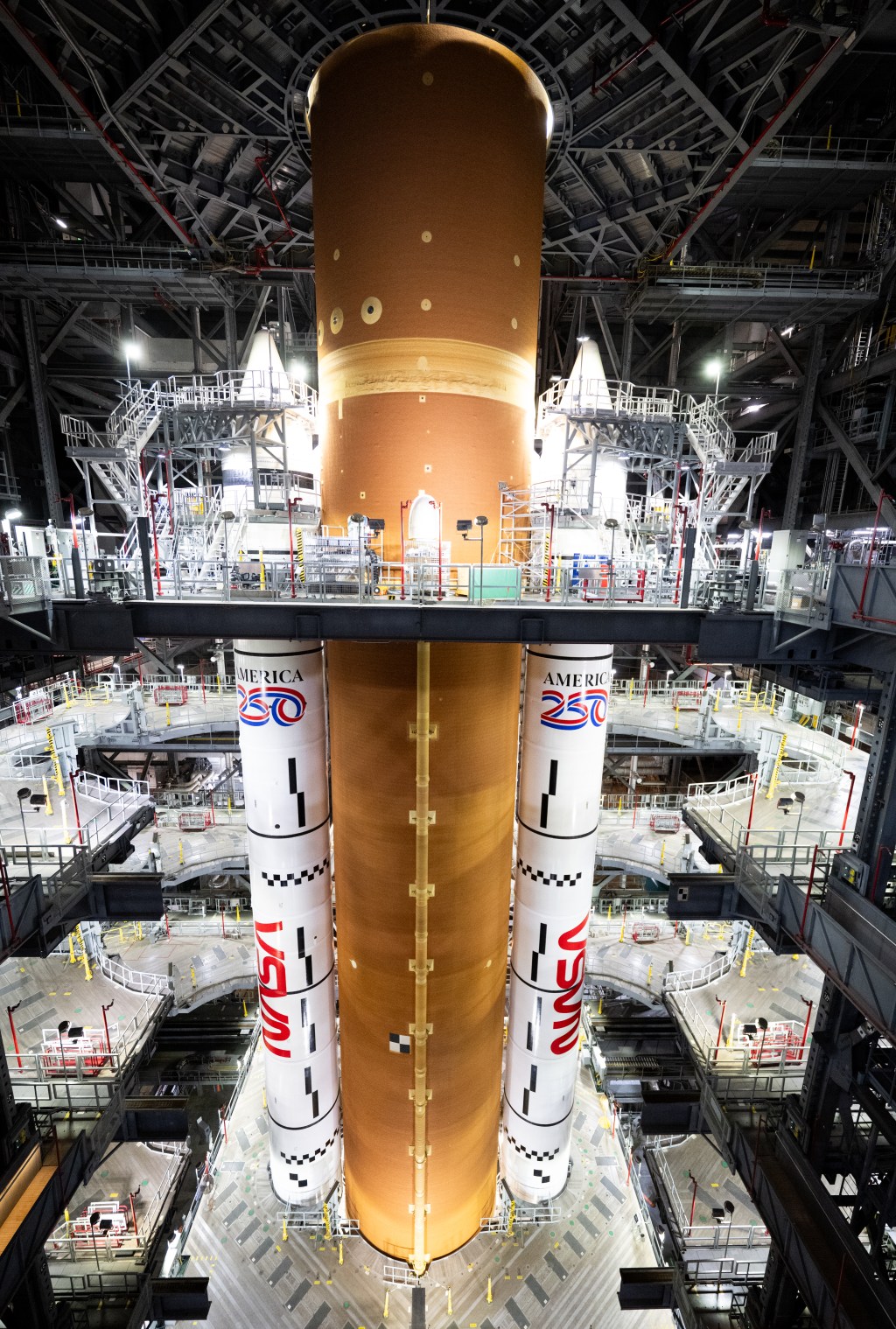

"The Martian" film highlights the radiation dangers that could occur on a round trip to Mars. While the mission in the film is fictional, NASA has already started working on the technology to enable an actual trip to Mars in the 2030s. In the film, the astronauts’ habitat on Mars shields them from radiation, and indeed, radiation shielding will be a crucial technology for the voyage. From better shielding to advanced biomedical countermeasures, NASA currently studies how to protect astronauts and electronics from radiation – efforts that will have to be incorporated into every aspect of Mars mission planning, from spacecraft and habitat design to spacewalk protocols.

“The space radiation environment will be a critical consideration for everything in the astronauts’ daily lives, both on the journeys between Earth and Mars and on the surface,” said Ruthan Lewis, an architect and engineer with the human spaceflight program at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “You’re constantly being bombarded by some amount of radiation.”

Radiation, at its most basic, is simply waves or sub-atomic particles that transports energy to another entity – whether it is an astronaut or spacecraft component. The main concern in space is particle radiation. Energetic particles can be dangerous to humans because they pass right through the skin, depositing energy and damaging cells or DNA along the way. This damage can mean an increased risk for cancer later in life or, at its worst, acute radiation sickness during the mission if the dose of energetic particles is large enough.

Fortunately for us, Earth’s natural protections block all but the most energetic of these particles from reaching the surface. A huge magnetic bubble, called the magnetosphere, which deflects the vast majority of these particles, protects our planet. And our atmosphere subsequently absorbs the majority of particles that do make it through this bubble. Importantly, since the International Space Station (ISS) is in low-Earth orbit within the magnetosphere, it also provides a large measure of protection for our astronauts.

“We have instruments that measure the radiation environment inside the ISS, where the crew are, and even outside the station,” said Kerry Lee, a scientist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

This ISS crew monitoring also includes tracking of the short-term and lifetime radiation doses for each astronaut to assess the risk for radiation-related diseases. Although NASA has conservative radiation limits greater than allowed radiation workers on Earth, the astronauts are able to stay well under NASA’s limit while living and working on the ISS, within Earth’s magnetosphere.

But a journey to Mars requires astronauts to move out much further, beyond the protection of Earth's magnetic bubble.

“There’s a lot of good science to be done on Mars, but a trip to interplanetary space carries more radiation risk than working in low-Earth orbit,” said Jonathan Pellish, a space radiation engineer at Goddard.

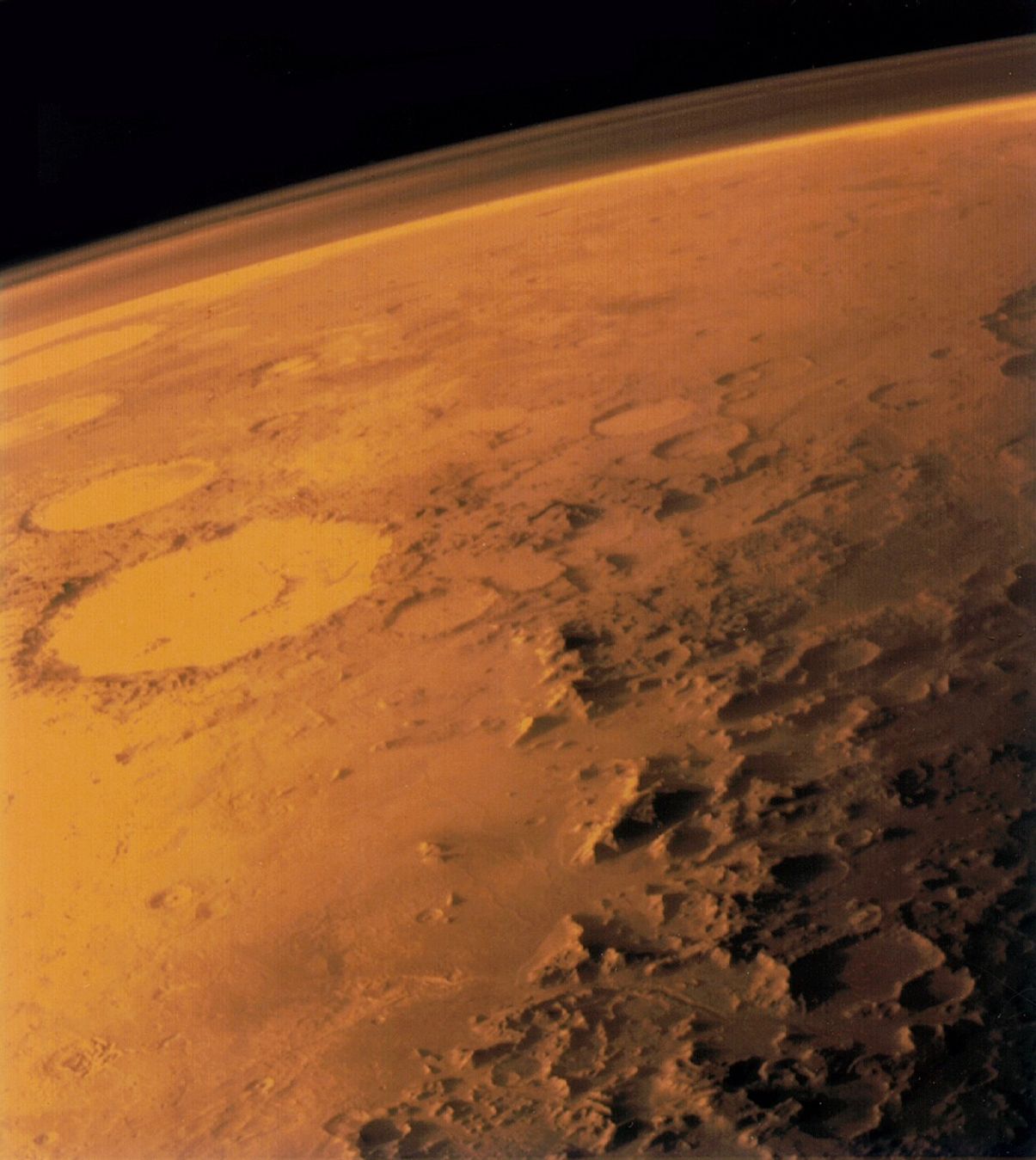

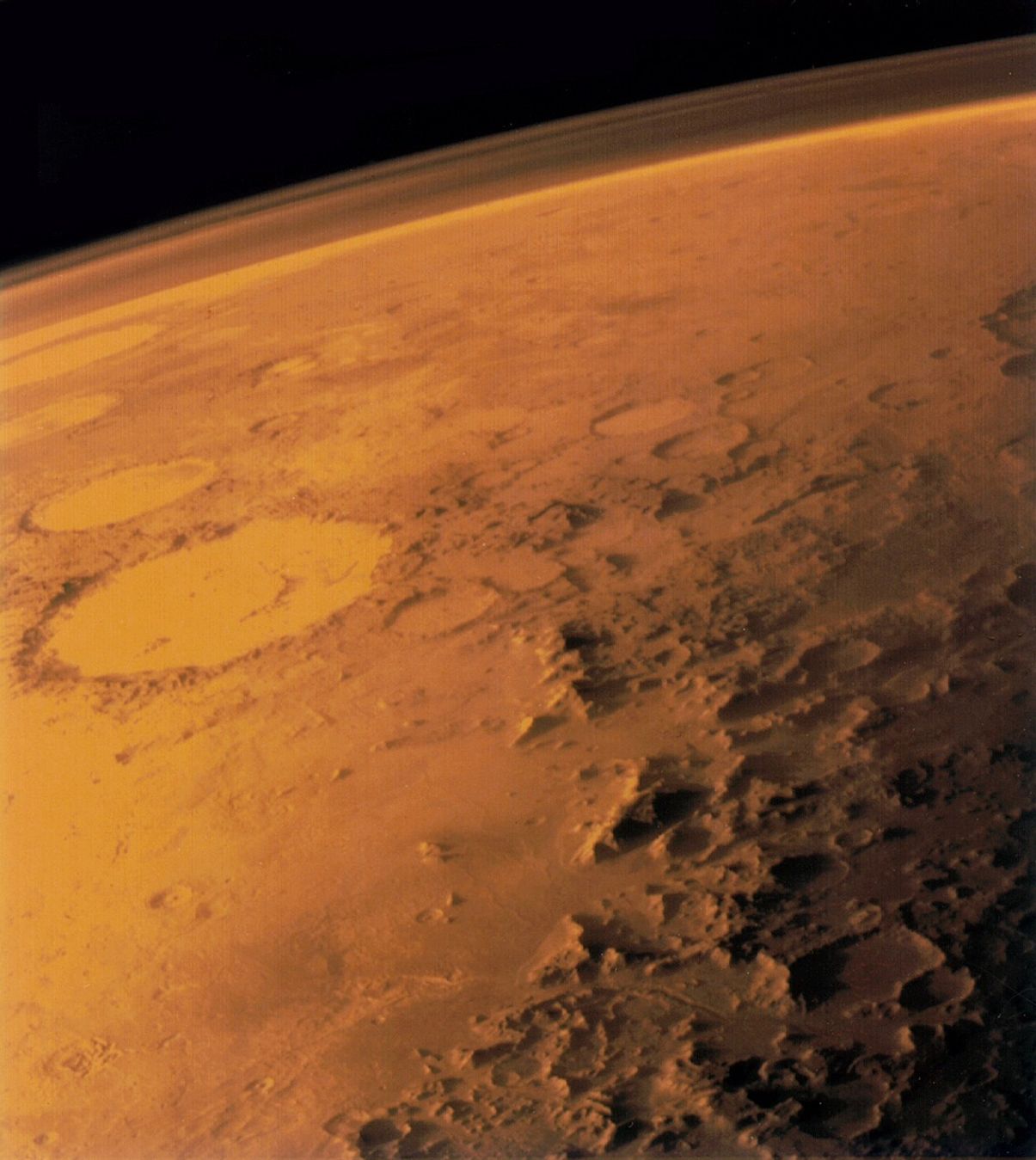

A human mission to Mars means sending astronauts into interplanetary space for a minimum of a year, even with a very short stay on the Red Planet. Nearly all of that time, they will be outside the magnetosphere, exposed to the harsh radiation environment of space. Mars has no global magnetic field to deflect energetic particles, and its atmosphere is much thinner than Earth’s, so they'll get only minimal protection even on the surface of Mars.

Throughout the entire trip, astronauts must be protected from two sources of radiation. The first comes from the sun, which regularly releases a steady stream of solar particles, as well as occasional larger bursts in the wake of giant explosions, such as solar flares and coronal mass ejections, on the sun. These energetic particles are almost all protons, and, though the sun releases an unfathomably large number of them, the proton energy is low enough that they can almost all be physically shielded by the structure of the spacecraft.

Since solar activity strongly contributes to the deep-space radiation environment, a better understanding of the sun’s modulation of this radiation environment will allow mission planners to make better decisions for a future Mars mission. NASA currently operates a fleet of spacecraft studying the sun and the space environment throughout the solar system. Observations from this area of research, known as heliophysics, help us better understand the origin of solar eruptions and what effects these events have on the overall space radiation environment.

“If we know precisely what’s going on, we don’t have to be as conservative with our estimates, which gives us more flexibility when planning the mission,” said Pellish.

The second source of energetic particles is harder to shield. These particles come from galactic cosmic rays, often known as GCRs. They’re particles accelerated to near the speed of light that shoot into our solar system from other stars in the Milky Way or even other galaxies. Like solar particles, galactic cosmic rays are mostly protons. However, some of them are heavier elements, ranging from helium up to the heaviest elements. These more energetic particles can knock apart atoms in the material they strike, such as in the astronaut, the metal walls of a spacecraft, habitat, or vehicle, causing sub-atomic particles to shower into the structure. This secondary radiation, as it is known, can reach a dangerous level.

There are two ways to shield from these higher-energy particles and their secondary radiation: use a lot more mass of traditional spacecraft materials, or use more efficient shielding materials.

The sheer volume of material surrounding a structure would absorb the energetic particles and their associated secondary particle radiation before they could reach the astronauts. However, using sheer bulk to protect astronauts would be prohibitively expensive, since more mass means more fuel required to launch.

Using materials that shield more efficiently would cut down on weight and cost, but finding the right material takes research and ingenuity. NASA is currently investigating a handful of possibilities that could be used in anything from the spacecraft to the Martian habitat to space suits.

“The best way to stop particle radiation is by running that energetic particle into something that’s a similar size,” said Pellish. “Otherwise, it can be like you’re bouncing a tricycle off a tractor-trailer.”

Because protons and neutrons are similar in size, one element blocks both extremely well—hydrogen, which most commonly exists as just a single proton and an electron. Conveniently, hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, and makes up substantial parts of some common compounds, such as water and plastics like polyethylene. Engineers could take advantage of already-required mass by processing the astronauts’ trash into plastic-filled tiles used to bolster radiation protection. Water, already required for the crew, could be stored strategically to create a kind of radiation storm shelter in the spacecraft or habitat. However, this strategy comes with some challenges—the crew would need to use the water and then replace it with recycled water from the advanced life support systems.

Polyethylene, the same plastic commonly found in water bottles and grocery bags, also has potential as a candidate for radiation shielding. It is very high in hydrogen and fairly cheap to produce—however, it’s not strong enough to build a large structure, especially a spacecraft, which goes through high heat and strong forces during launch. And adding polyethylene to a metal structure would add quite a bit of mass, meaning that more fuel would be required for launch.

“We’ve made progress on reducing and shielding against these energetic particles, but we’re still working on finding a material that is a good shield and can act as the primary structure of the spacecraft,” said Sheila Thibeault, a materials researcher at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia.

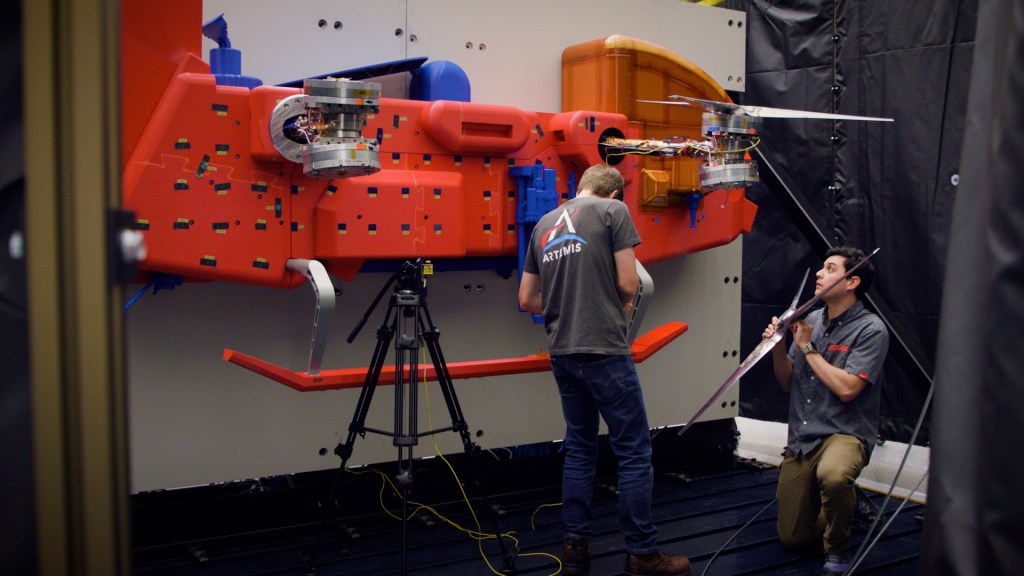

One material in development at NASA has the potential to do both jobs: Hydrogenated boron nitride nanotubes—known as hydrogenated BNNTs—are tiny, nanotubes made of carbon, boron, and nitrogen, with hydrogen interspersed throughout the empty spaces left in between the tubes. Boron is also an excellent absorber secondary neutrons, making hydrogenated BNNTs an ideal shielding material.

“This material is really strong—even at high heat—meaning that it’s great for structure,” said Thibeault.

Remarkably, researchers have successfully made yarn out of BNNTs, so it’s flexible enough to be woven into the fabric of space suits, providing astronauts with significant radiation protection even while they’re performing spacewalks in transit or out on the harsh Martian surface. Though hydrogenated BNNTs are still in development and testing, they have the potential to be one of our key structural and shielding materials in spacecraft, habitats, vehicles, and space suits that will be used on Mars.

Physical shields aren’t the only option for stopping particle radiation from reaching astronauts: Scientists are also exploring the possibility of building force fields. Force fields aren't just the realm of science fiction: Just like Earth’s magnetic field protects us from energetic particles, a relatively small, localized electric or magnetic field would—if strong enough and in the right configuration—create a protective bubble around a spacecraft or habitat. Currently, these fields would take a prohibitive amount of power and structural material to create on a large scale, so more work is needed for them to be feasible.

The risk of health effects can also be reduced in operational ways, such as having a special area of the spacecraft or Mars habitat that could be a radiation storm shelter; preparing spacewalk and research protocols to minimize time outside the more heavily-shielded spacecraft or habitat; and ensuring that astronauts can quickly return indoors in the event of a radiation storm.

Radiation risk mitigation can also be approached from the human body level. Though far off, a medication that would counteract some or all of the health effects of radiation exposure would make it much easier to plan for a safe journey to Mars and back.

“Ultimately, the solution to radiation will have to be a combination of things,” said Pellish. “Some of the solutions are technology we have already, like hydrogen-rich materials, but some of it will necessarily be cutting edge concepts that we haven’t even thought of yet.”

Sarah Frazier

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Editor: Rob Garner