Warm and Dry on Iapetus

| PIA Number | PIA10012 |

|---|---|

| Language |

|

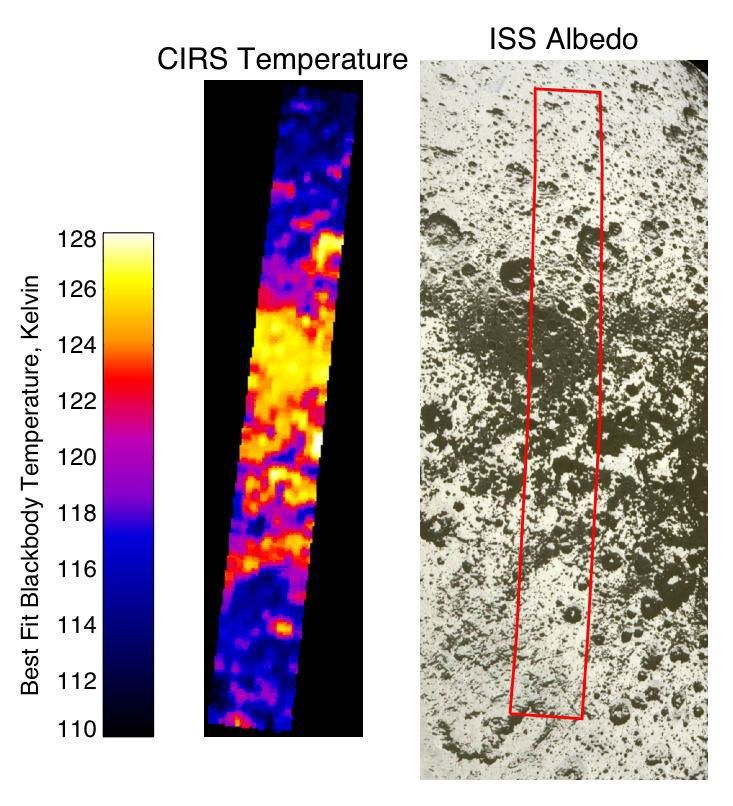

This image compares midday temperatures on Saturn's moon Iapetus, recorded by the composite infrared spectrometer instrument during Cassini's close Sept. 10, 2007 flyby, with images of the same region recorded during the same flyby by the Cassini imaging science subsystem, shown on the right. See The Other Side of Iapetus for full imaging mosaic.

Smallest features visible in the composite infrared spectrometer image (on the left) are about 8 kilometers (5 miles) across. The red rectangle on the visible light (right) image shows the region covered by infrared spectrometer, which extends a distance of 385 kilometers (240 miles) from 36 north, 212 west to 22 south, 220 west. The composite infrared spectrometer determined surface temperatures by measuring the spectrum of infrared radiation emitted by Iapetus in the 9 to 16 micron wavelength range. The dark regions are warmer because they absorb more of the sunlight shining on Iapetus, so dark spots in the visible (right) image show up as warm spots in the infrared image on the left. Temperatures near the equator vary between about 128 Kelvin (minus 229 degrees Fahrenheit) in the darkest regions and about 113 Kelvin (minus 256 degrees Fahrenheit) in the brightest regions.

This relatively small temperature difference has a large effect on Iapetus, because at the temperature of the dark regions, a large amount of water ice, which is abundant on most moon surfaces in the Saturn system, can be lost by evaporation over the several-billion year age of Iapetus' surface. Composite infrared spectrometer scientists calculate that when daytime temperatures reach 128 Kelvin (minus 229 degrees Fahrenheit), about 20 meters (65 feet) of ice can be lost per billion years. In the bright regions, with peak temperatures of 113 Kelvin (minus 256 degrees Fahrenheit), only about 10 centimeters, or 2.5 inches, of ice is lost in the same period. It is thus likely that the ice has evaporated completely from the surface of the dark regions of Iapetus, darkening them further, and has collected in the neighboring bright regions, making them brighter, thereby exaggerating initially modest brightness variations. This process is known as thermal segregation.

Models by the composite infrared spectrometer team also show that ice evaporated from the warm dark terrain at low latitudes can collect at higher latitudes, and can thus explain the bright polar caps on the dark leading side of Iapetus as well as the relatively dark equatorial regions on the bright trailing side.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C. The Cassini orbiter was designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The composite infrared spectrometer team is based at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md. The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov . The composite infrared spectrometer team homepage is http://cirs.gsfc.nasa.gov/. The Cassini imaging team homepage is at http://ciclops.org .

Credit: NASA/JPL/GSFC/SwRI/SSI