NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will conduct rapid surveys of wide swaths of the universe, unveiling new worlds and clues to mysteries like the nature of dark energy and dark matter. Since each Roman image will reveal such a large area, astronomers will have practically limitless opportunities to explore the cosmos. Working in tandem with observatories such as the James Webb Space Telescope will offer the most complete picture of the universe yet.

Roman’s surveys will offer a broad view of cosmic ecosystems and pinpoint rare objects. Webb can use its narrower view but more powerful vision to follow up on those uncommon objects for even more detailed observations, and Roman can view regions Webb has observed to offer context. Together, the two observatories will reveal extraordinary new information about our universe such as primordial galaxies, black holes, and planets beyond our solar system.

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Far and Wide

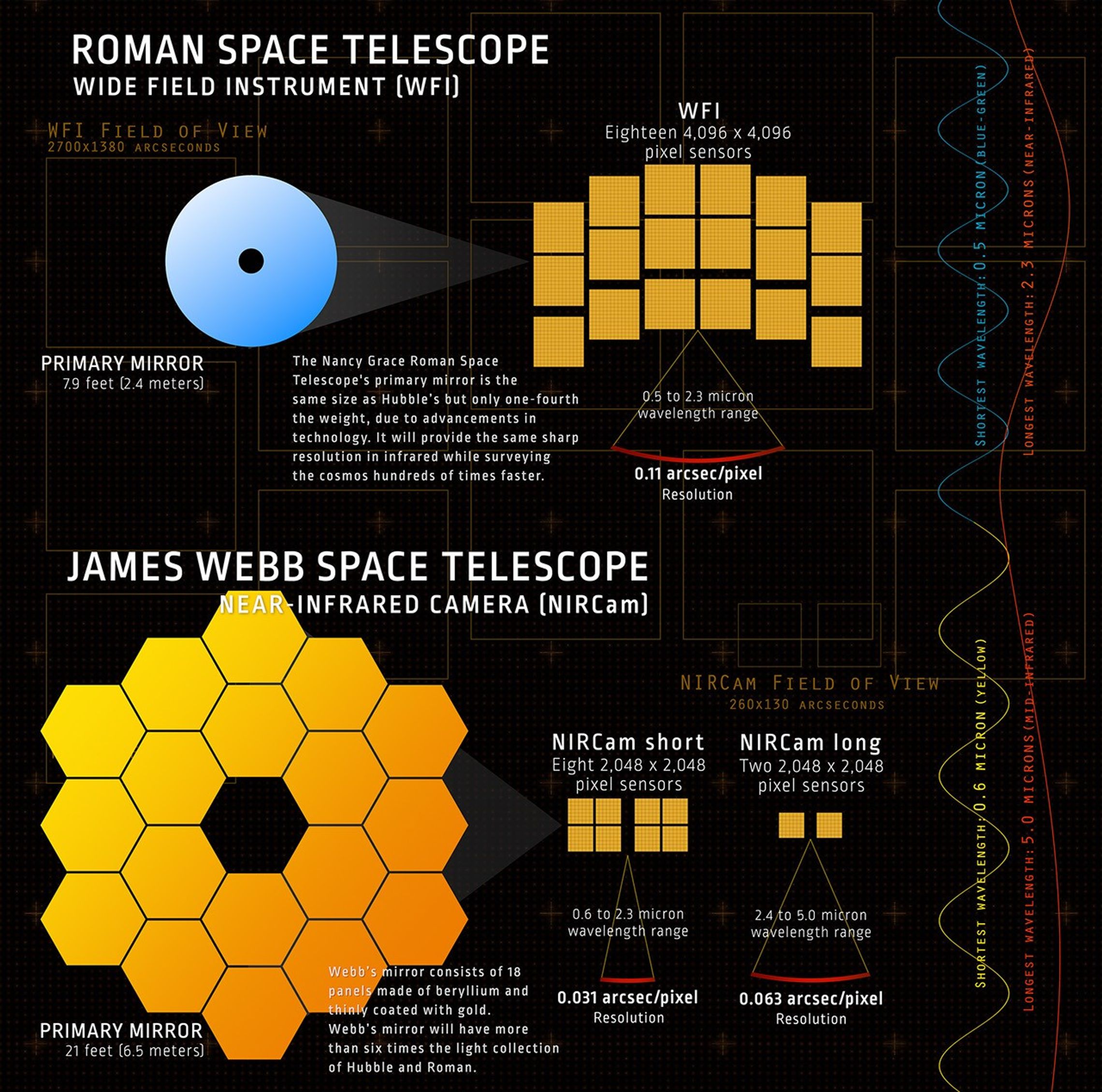

While Roman will capture images 50 times larger than Webb can, Webb sees farther back in time with higher resolution. That’s because Webb’s primary mirror is so large — 21 feet (6.5 meters) versus 7.9 feet (2.4 meters) for Roman’s. Webb sees more detail because its larger mirror will collect more light, just like a bigger bucket collects more water in a rain shower than a small one.

Roman owes its panoramic view to its 18 large detectors and its wide-field telescope design. This gives Roman an ability that’s rare among space telescopes — it can efficiently explore space even if astronomers don’t have a particular target in mind. Since it will see such a large area of the universe at any given time, Roman will discover uncommon events that space telescopes have historically only been able to observe after ground-based telescopes have identified them. The mission will spot phenomena such as colliding neutron stars that Webb will likely never detect on its own with its narrow view.

Both Roman and Webb will primarily study the universe in infrared light, allowing them to see warm objects, peer into dusty regions, and gaze across vast stretches of space. Pairing Webb’s powerful observations, which probe even farther into the infrared, with Roman’s big-picture view will reveal untold cosmic wonders. Their overlapping wavelength ranges will allow astronomers to compare their observations to learn much more than from either mission alone.

Cosmology

Together, Roman and Webb will unlock enormous stretches of the universe’s history. Astronomers will use observations of different cosmic eras to piece together how the universe transformed over billions of years to its present state.

Dark Energy

Scientists have discovered that the universe’s expansion is speeding up, but no one knows why. A mysterious pressure dubbed “dark energy” has been theorized as a possible explanation. Exploring the nature of dark energy is one of Roman’s primary goals, and Webb will offer clues, too.

Roman will combine the powers of imaging and spectroscopy to unveil more than a billion galaxies. Imaging will reveal the locations, shapes, sizes, and colors of objects like distant galaxies, and spectroscopy will measure the intensity of light from those objects at different wavelengths, allowing astronomers to determine how far away they are.

Doing both across the same enormous swath of the universe will yield enormous, deep 3D images that will help astronomers discern between the leading theories that attempt to explain why the expansion of the universe is accelerating. Webb has powerful spectrographs too, but its smaller view renders it impractical to survey enough sky to measure large-scale galaxy clustering, which carries the imprint of dark matter and dark energy.

Roman will also trace cosmic expansion using a special kind of exploding star called a type Ia supernova. These explosions, which happen roughly once every 500 years in the Milky Way, peak at a similar, known intrinsic brightness. That allows astronomers to determine how far away the supernovae are by simply measuring how bright they appear. Astronomers can study the light of these supernovae to find out how quickly they appear to be moving away from us.

By comparing how fast they’re receding at different distances, scientists will trace cosmic expansion across billions of years. This will help us understand whether and how dark energy has changed throughout the history of the universe, and could clear up mismatched measurements of the Hubble constant — the universe’s current expansion rate.

Roman’s gigantic view will cast such a wide net that astronomers will see thousands of type Ia supernovae. Webb can study these explosions more closely to help refine the way they’re used to determine cosmic distances.

Dark Matter

Roman and Webb will also add pieces to the dark matter puzzle—another key component of the universe that we don’t understand well. This invisible material is detectable only through its gravitational effects on normal matter. Scientists are trying to determine what exactly dark matter is made of so they can detect it directly, but our current understanding has so many gaps, it’s difficult to know just what we’re looking for.

In its very first science image, Webb found dark matter hidden among distorted galaxies. Anything with mass warps the fabric of space-time — the greater the mass, the stronger the warp. Light that passes nearby follows the curved path around the object. For things as large as galaxies and galaxy clusters, this effect—called gravitational lensing — can warp light so strongly that distant galaxies are smeared into arcs and streaks in images. Astronomers can determine how massive an intervening object is by seeing how much it distorts light from more distant sources.

Roman will be sensitive enough to use a more subtle version of the same effect (called weak lensing) to see how clumps of dark matter warp the appearance of distant galaxies. By observing lensing effects on this small scale over a gigantic area, Roman will map how dark matter is distributed and explore its structure. This will help astronomers fill in more of the gaps in our understanding of dark matter. Their findings could even lead to adjustments to our current cosmological model of the universe.

Early Universe

Webb is on the hunt for galaxies forming in the universe’s youth, just a few hundred million years after the big bang. When Roman joins the search it likely won’t see quite as far back as Webb, but its large field of view will reveal how young galaxies are distributed — presumably tracing the vast filaments of dark matter that scientists think are the seeds of galaxy formation — and will help astronomers understand whether galaxy formation is affected by the local environment.

Cosmic Dawn

Webb and Roman both aim to study the period when the first stars and galaxies appeared, known as the cosmic dawn. In this early stage, space looked very different than it does today. The universe was filled with an opaque hydrogen gas. Eventually the gas gravitated together to form stars and galaxies, though some still permeated the spaces in between and absorbed starlight.

Quasars — brilliant beacons of intense light powered by a supermassive black hole — are nestled in the cores of some of these galaxies. The black hole voraciously feeds on infalling matter and unleashes a torrent of radiation. Radiation from galaxies and quasars may have been key to ending the cosmic “dark ages” by clearing up the hydrogen fog to make the universe transparent.

Even if galaxies crowd the sky in the early universe, quasars that are bright enough for astronomers to see from Earth are few and far between. Roman’s enormous view should pinpoint enough quasars that Webb will be able to discover details about what infant galaxies are like as a group — not just as individuals. Finding a sufficient sample using Webb alone would be impractical.

The observations will offer clues about how galaxies formed from the primordial gas that once filled the universe, and how their central supermassive black holes influenced galaxy and star formation. Webb’s deeper imaging and spectroscopy will unveil the early universe in unprecedented detail, and Roman’s larger view will make it easier to see how the cosmos evolved over time.

Near and Far

Roman’s surveys of nearby galaxies will also offer clues about the early universe. Roman will reveal streams of stars, the remnants of dwarf galaxies or star clusters that larger galaxies absorbed, offering archeological clues about how the first galaxies formed. Roman’s and Webb’s tandem observations of both large nearby galaxies and their smaller companions will allow astronomers to compare how galaxies of very different sizes evolved.

Roman may even detect supernova explosions from the deaths of the first stars. Webb could take a closer look at all these objects to learn things like how different elements formed and became distributed in galaxies in the early universe. It will also help us learn more about the roles different types of objects played in ending the cosmic dark ages.

Star Formation

As Roman unveils the universe, its enormous view of space will also help astronomers quickly find fascinating, rare cosmic objects that could take decades to search for with Webb. Then Webb can zoom in for a detailed look no other existing observatory could provide. The two telescopes will team up to use each of their strengths to study topics like star formation.

Stars are fiery nuclear furnaces that make life possible on Earth and potentially elsewhere in the universe. Many undergo dynamic processes that are difficult to study from afar. Webb’s near- to mid-infrared spectroscopy offers invaluable new insight into stellar activities.

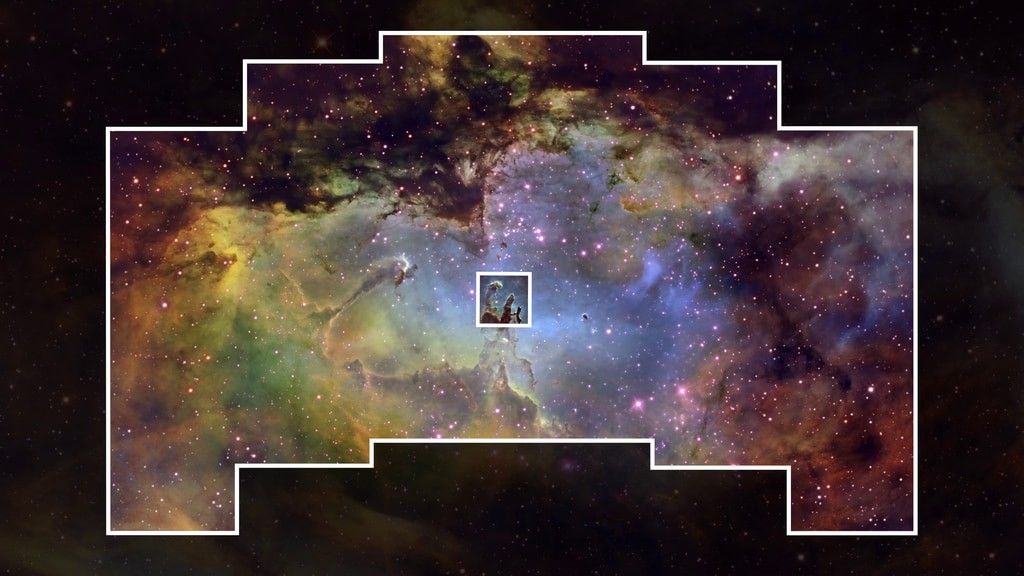

But its narrow view makes it tough to spot particularly interesting regions within star-forming clouds and clusters of stars. Roman’s larger space panoramas will provide a roadmap, highlighting the best places for Webb to look. Together, the two telescopes could study areas such as the Taurus Molecular Cloud, which is home to myriad stars in different stages of formation. They could even study star-forming clouds and young star clusters in some of our neighboring galaxies, like the Andromeda galaxy. Webb’s images offer fine detail, and Roman’s big view will provide ample targets Webb may follow up on for further study.

Exoplanets

Astronomers have discovered more than 6,000 worlds outside our solar system, known as exoplanets. But most of them are wild and exotic compared to what astronomers expected to find — planets like those in our solar system. Roman and Webb will team up to help us understand more about these strange worlds and also discover troves of planets with more familiar characteristics.

Pictures of Planets

Both missions will come equipped with coronagraphs — instruments that block starlight to reveal fainter orbiting planets. Webb is using its coronagraph to directly image exoplanet in infrared light and spot hot, young planets near bright stars. Panoramas of stellar nurseries produced by Roman could provide Webb with plentiful targets to zoom in on by identifying young stars that may still be encircled by planet-forming disks.

Roman’s Coronagraph Instrument technology demonstration will also directly image planets, but in visible light, allowing astronomers to see older, colder worlds. The mission aims to photograph planets and dusty disks that are up to a thousand times fainter relative to their host stars than other observatories can image.

This will pave the way for future telescopes to use similar tech to observe and characterize rocky planets in their star’s habitable zone — the range of orbital distances where liquid water could exist on a planet’s surface. In the meantime, Webb will teach us how planets are born, while Roman will see more mature worlds similar to some of the planets in our outer solar system.

Finding New Worlds

Roman will also find more than a thousand exoplanets via microlensing. A microlensing event occurs when two unrelated stars nearly align in the sky from our vantage point. The nearer star — and any orbiting planets—can focus or “lens” light from the background star, temporarily brightening the distant star. While most currently known planets orbit close to their host stars, microlensing is best suited to finding worlds farther out, including some in their star’s habitable zone.

Since Roman’s microlensing survey will monitor the amount of starlight we receive from hundreds of millions of stars, it could also discover as many as 100,000 more planets thanks to the transit method. This technique also involves measuring starlight, but looks for periodic dimming that happens when a planet crosses in front of its host star and blocks some of its light.

Analyzing Atmospheres

Webb observes transiting planets to study their atmospheres. By decoding the starlight that filters through planetary atmospheres, Webb offers information about the planets’ clouds, weather, atmospheric gases, and rotation. The mission is even searching for atmospheres around potentially habitable worlds.

Together, Roman and Webb will divulge new data about exoplanets with a wide range of sizes, ages, orbital distances, and environments. Adding to what we’ve learned from other telescopes, their findings will offer the best information to date about how planetary systems form and evolve.

Roman and Webb are both powerful tools to study the infrared universe, and they’ll work even better together. Roman will cast a wide net and see an enormous number of objects, and Webb will see fewer things in greater detail. An exciting new era of cosmic discovery awaits!

Video 2: Surveying the Universe

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Video 3: Exoplanets

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Video 4: Teamwork

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center