Lightning is as beautiful as it is powerful – a violent, hotter than the surface of the Sun electrical marvel. But might lightning on other planets be even more astonishing?

Consider this. When Voyager 1 flew by Jupiter in 1979, its imager captured areas nearly as big as the U.S. lit up by lightning in Jupiter’s clouds.

Voyager also captured other, less ‘flashy’ signs of lightning. University of Iowa physicist Don Gurnett is one of the scientists whose Voyager instrument detected radio waves called whistlers -- signs of lightning.

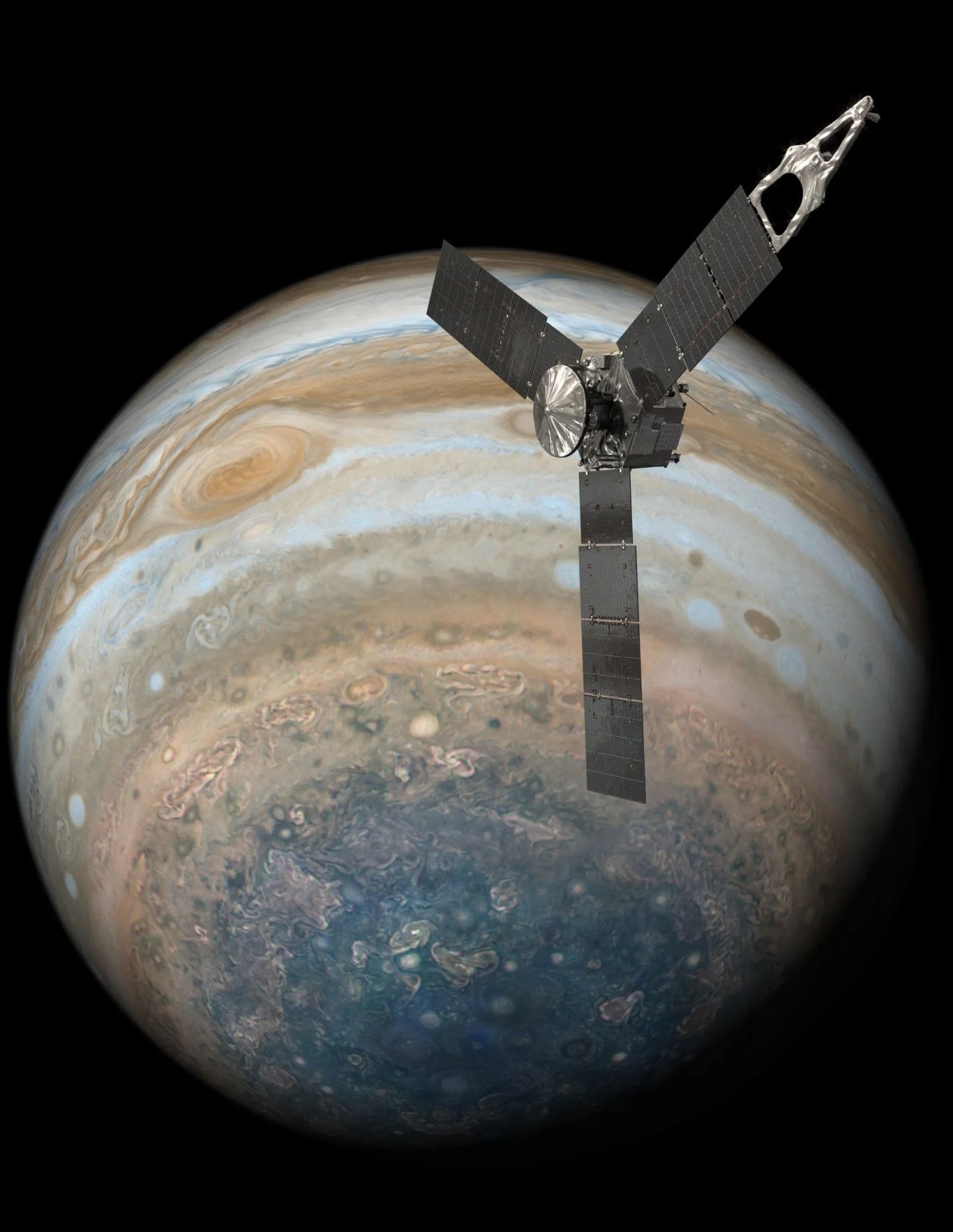

New Horizons cameras captured lightning flashes on Jupiter ten times as powerful as anything ever recorded on Earth. And recently Juno, flying closer to Jupiter than any previous mission, found that most of Jupiter’s lightning is around the planet’s higher latitudes, unlike Earth, where lightning strikes primarily over land and most intensely at the equator. Juno detected peak rates of four strikes per second -- similar to rates on Earth.

On Earth, lightning forms because colliding ice crystals and water drops inside clouds create positive and negative electric charges which become separated by convective forces. When the charges become separated enough, a lightning bolt discharges. Something similar happens on Jupiter. Gases, including water vapor, rise from deep within the planet. As they freeze, ice particles become separated from the water drops by convection, building a charge, which is discharged as lightning.

Lightning has also been observed on gas giant Saturn. In 1980-81, Voyager detected radio signals called sferics, which like whistlers are signs of lightning.

Gurnett says, “On Earth, you can hear these high-frequency radio emissions on your car’s AM radio as ‘radio static’ during a nearby lightning storm.”

Cassini recorded similar emissions at Saturn, revealing that, for strong storms, lightning occurred as many as ten times per second!

Gurnett has been involved in the search for lightning on other planets across the solar system as well.

Venus, for example, has a hot, dry atmosphere made up mostly of carbon dioxide suffused with sulfuric acid. Could this brew become electrically charged and generate lightning? When Cassini flew by Venus twice in 1998 and 1999 Gurnett did a search for lightning with a radio instrument perfect for detecting signs of lightning sferics. However the instrument picked up no signs at all. That same instrument easily detected sferics during a similar flyby of Earth two months later, leading him to believe that there is no Earth-like lightning present on Venus.

The European Space Agency’s Venus Express orbiter has picked up bursts of electromagnetic waves some scientists attribute to whistlers, but others argue that the instrument’s frequency range was too low to detect the usual forms of whistlers.

Gurnett has used Mars Express’s radar system receiver to conduct a five year search for lightning associated with dust storms on Mars. That search didn’t find lightning, however, images from the Mars Global Surveyor show bright flashes in dust storms, as well as craters on Mars that some scientists believe to be evidence of lightning strikes on the planet’s surface.

Stay tuned as this electric story unfolds on science.nasa.gov.