Featured Tips

-

01

What’s Up: Skywatching Tips from NASA

The What's Up monthly skywatching guide is NASA's longest running web video series. Watch the video and read the article.

The Milky Way over the mountains near Ephraim, Utah.NASA/Bill Dunford

The Milky Way over the mountains near Ephraim, Utah.NASA/Bill Dunford -

02

Meteor Showers

Several meteors per hour can usually be seen on any clear night. When there are lots more meteors, you’re watching a meteor shower.

The Perseids meteor shower peaks in mid-August. It is one of the most popular meteor showers of the year.NASA/Preston Dyches

The Perseids meteor shower peaks in mid-August. It is one of the most popular meteor showers of the year.NASA/Preston Dyches -

03

What is a Planet Parade?

On most nights, weather permitting, you can spot at least one bright planet in the night sky. While two or three planets are commonly visible in the hours around sunset, occasionally four or five bright planets can be seen simultaneously with the naked eye. These events, often called "planet parades." Though not exceedingly rare, they're worth observing since they don't happen every year.

A sky chart showing Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and Venus in a "planet parade."NASA/JPL-Caltech

A sky chart showing Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and Venus in a "planet parade."NASA/JPL-Caltech -

04

NASA's Night Sky Network

Astronomy clubs bringing the wonders of the universe to the public.

-

05

Hubble's Night Sky Challenge

Help celebrate Hubble’s 35th anniversary by joining our year-long stargazing challenge.

A tripod stabilizes a DLSR camera while it images the night sky.Neil Zeller

A tripod stabilizes a DLSR camera while it images the night sky.Neil Zeller -

06

NASA/Scientific Visualization Studio

NASA/Scientific Visualization Studio -

07

Photo by Gunjan Sinha, acquired on May 11, 2024, from near Saskatoon in Saskatchewan, Canada.Gunjan Sinha

Photo by Gunjan Sinha, acquired on May 11, 2024, from near Saskatoon in Saskatchewan, Canada.Gunjan Sinha

How To...

Explore NASA's tips and guides for observing and photographing the sky.

Photograph the Moon

Capturing the Moon with a camera is one of the most satisfying – and challenging – projects available to an outdoor photographer.

Use Binoculars for Skywatching

Binoculars are an excellent first instrument for skywatching because they are generally easy to use and more versatile than most telescopes.

Photograph a Meteor Shower

Taking photographs of meteors streaking across the sky can be challenging, but with these tips - you might be rewarded with a great photo.

Find Good Places to Stargaze

If you're hoping to do some skywatching, but you're not quite sure how to find a great spot, we have you covered.

What to Look for in the Sky

-

01

Planets

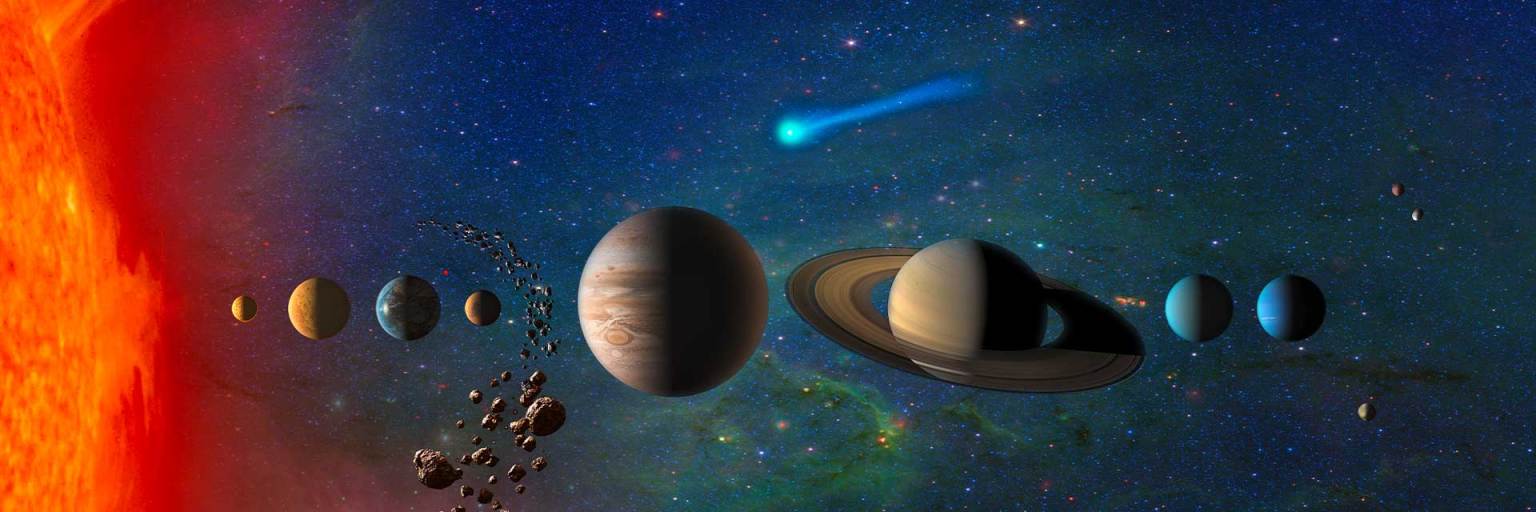

Five planets in our solar system are easily observed without a telescope: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Uranus is just barely visible for those with excellent eyesight under dark-sky conditions, provided you know where to look. The planets appear to move across the sky, against the background of the much more distant stars. Planets appear as bright or brighter than most stars, and unlike stars, they tend to glow with a steady light, where stars often flicker.

-

02

Stars

Most of the brightest stars are relatively nearby in space – that is, within a few hundred light years of the solar system. While there are a couple hundred billion stars in our galaxy, the Milky Way, we only see a few thousand of the nearer ones when we look into the night sky with our eyes. Stars are spread all across the canvas of the sky, but they appear denser in places. For example, there are clusters of stars, like the Pleiades, and the region of the sky where the band of the Milky Way appears is much more densely packed. And because our brains are especially good at finding patterns, we also observe groupings of stars that form constellations and asterisms.

-

03

Earth's Moon

Earth's Moon is a constantly changing celestial sight, from night to night. It goes through phases each month, waxing as it becomes full, and waning as the full moon shrinks back to a crescent. The Moon's changing illumination causes different features on its surface, like craters and mountain ranges, to appear more prominently as they become highlighted along the day-night dividing line, called the terminator.

-

04

Meteor Showers

Meteors are tiny bits of rock and dust shed by comets and asteroids in debris trails as they orbit our Sun. Every year, at about the same time, our planet passes through the same debris trails, causing the annual named meteor showers. Some of the best known showers, like the Perseids and Geminids, and can wow spectators with dozens of meteors per hour at their peak.

-

05

Comets

Dusty, icy comets hail from the cold depths of the outer solar system, far from the warmth of our Sun. Some, like Comet Halley, are on relatively short orbits of decades to a couple hundred years. Others have orbits that take many thousands of years to circle the Sun. Comets are special, occasional visitors, that don't stick around. They start out faint and distant, requiring a telescope to be seen. But as they come closer to the Sun, they can brighten and form a fuzzy head, called a coma. The most spectacular comets also form long, streamer-like tails.

-

06

Eclipses

There are two main types of eclipses: solar and lunar. Solar eclipses are observed in the daytime when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, and covers the Sun from our point of view, either partially or totally. Lunar eclipses are observable when the Moon is above the horizon and Earth passes between the Moon and the Sun, causing our planet's shadow to fall across the Moon's surface. Lunar eclipses can also be partial, where only part of the Moon falls into shadow, or total. Importantly, solar eclipses should never be viewed with unprotected eyes, while lunar eclipses are safe to view with the naked eye.

-

07

Spot the Space Station

Watch the International Space Station pass overhead! NASA’s Spot the Station mobile app and website make it easy to find.

-

08

Satellites

Satellites are easiest to spot around dawn and dusk. Since they orbit high above Earth, they are often bathed in sunlight, while you are sitting in twilight below. Satellites tend to be fainter than passing airplanes, and unlike aircraft, they don't have beacon lights that blink regularly (though some can brighten suddenly in what's called a flare). Satellites often can be seen to fade in brightness as their orbits carry them into darkness above the planet's night side. Alternately, they can appear from nothing, brightening as they head into day, experiencing an orbital sunrise.

-

09

Galaxies

Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, appears as a band of faint light across the night sky in dark locations away from bright city lights. Our solar system lies within the disk of the Milky Way, so we are looking at it edge on. Observers in the Southern Hemisphere are able to observe the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds – two dwarf galaxies that orbit the Milky Way. Observers sometimes describe their appearance as being like faint clouds in the night sky. Our nearest large neighbor, the Andromeda galaxy, appears as a faint, fuzzy patch of light in Northern Hemisphere skies.

-

10

Auroras

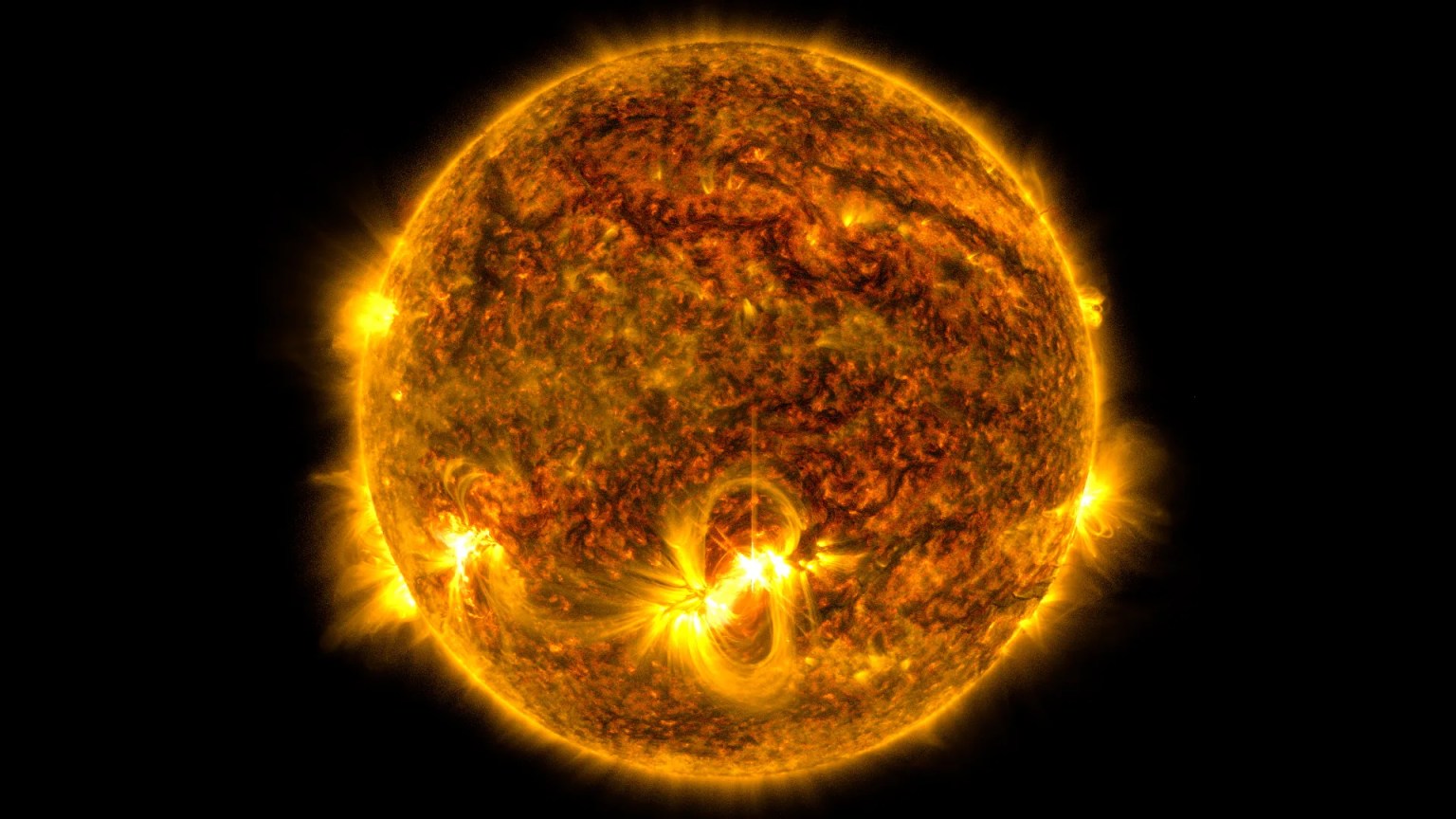

Usually a treat enjoyed by those who live at higher latitudes toward the north or south, auroras are dancing curtains of light and color in the sky. They are the result of our planet's magnetic field and atmosphere interacting with those of the Sun. A wind of particles from our local star washes continuously over our planet, and sometimes becomes more intense. Some of those electrically charged particles become trapped in Earth's magnetic force field and get funneled into our upper atmosphere, where they produce glowing light displays as they crash into molecules of gases like oxygen and nitrogen.

NASA's Eyes: Telescope Mode

Check out the NASA's Eyes on the Solar System Telescope mode! Click anywhere on Earth and then click "GO" in order to land at that location. Click the Big Dipper icon at bottom to turn the constellations on and off, and see what's in the sky right now above that location.

Skywatching Tools

- Your Own Eyes You don't have to have any special gear to do skywatching. For most people, our own eyes are often the best way to enjoy observing. Your eyes can take in panoramic views of the sky spanning 180 degrees, whereas a telescope shows only a tiny patch of the sky. Some sights are only visible when seen with the naked eye – star patterns like the constellations, lineups of the planets, and the arc of the Milky Way to name a few examples. And meteor showers are best experienced by simply lying down and looking up!

- Binoculars & Spotting Scopes Often the answer to the question, "What is the best telescope for a beginning observer?" is "A pair of binoculars." Perhaps their greatest advantage is their portability and ease of use, in addition to their generally lower pricetag, compared to telescopes. They come in a similar spectrum of sizes and cost. Binoculars will show you a wider area of sky than a telescope, which can be an advantage when observing objects like comets and close pairings of the planets with the Moon. They easily reveal sights like star clusters, double stars, and the four largest moons of Jupiter, along with stars too faint to see with your eyes alone. Binoculars can be handheld, but they are a much more useful tool when stably mounted on a tripod. (They tend to be more enjoyable to use when mounted, as well!) As the main control mechanism is simply to focus them, binoculars tend to be easier to use than all but the simplest telescopes. An even easier option is a spotting scope, or monocular. Often used for birding and hunting, spotting scopes are as portable as binoculars, but they remove the need to adjust the two eyepieces to get a clear view.

- Telescopes Telescopes let you see objects your eyes can't detect. Telescopes also are great for observing the planets, comets, the Moon, and brighter nebulas and galaxies. Telescopes come in lots of sizes and configurations – from fully automated, desktop-sized, point and click models you control with an app, to large, open-frame scopes you can build yourself. They can be fully manual in operation – where you point them where you like using your hands – or driven by motorized mounts with computerized tracking systems. Here are some tips on how to pick a telescope.

- Cameras Digital cameras are capable of capturing incredible views of the night sky, as they can take long exposures that capture light from faint sources, including dim stars and the Milky Way itself. Night sky photography can be an expensive hobby, but it doesn't have to be. The essentials are just a digital camera, a lens that can open up to a wide aperture to collect more light, and a tripod for stability. (With lenses, look for ones with an aperture or "f number" of at least f/3.5. Numbers even lower, like f/1.8, are best, because they mean more light collecting ability!) Even the cameras in some smartphones are able to take decent night sky photos when placed on a stable surface or tripod. The main point to remember is that you can start skywatching, tonight, with your eyes alone, and still observe some really interesting sights. The various tools available are just that – options to add to the experience. If you decide you're ready to try scopes or cameras, remember you can start small and simple, and work your way to greater complexity as your interest deepens. And of course, if you're more into armchair observing, NASA has tons of dazzling images from space telescopes and solar system exploration missions to marvel at.

NASA's Role in Skywatching

An important part of NASA's mission is to explore – to go, to discover, and to learn – for the good of all. The agency's science missions extend our human senses deep into space, from Earth's Moon to planet Mars, from our star to distant stars and galaxies, from our own planet to exoplanets orbiting other suns. NASA's fleet of scientific exploration missions bring the cosmos closer by collecting images and other data to show us distant wonders in the sky like we could never see from Earth's surface. And with missions that explore the Sun and its family of planets and other small worlds, we actually take you there.

While stargazing and marveling at the beauty of the night sky is an ancient activity, it's only in the past few centuries that humans have had an opportunity to understand what they are looking at in the heavens above. And since its founding in 1958, NASA has endeavored to contribute to that shared understanding of our planet's place in the universe, through our scientific exploration.

For example, today we know Mars is not just a wandering, reddish point of light, but a complex world, thanks in part to the many spacecraft NASA has sent to explore the Red Planet. We know that most stars in the sky have systems of planets, with thousands of these exoplanets being added to the known worlds, in part thanks to NASA's exoplanet research. And with NASA's space telescopes, scientists have peered into the hearts of distant nebulas to reveal the stellar nurseries where baby stars are born.

NASA's skywatching resources are shared in that same spirit of exploration. We recognize that there's an explorer in each of us, and we want you to remember that the wonders of space are not something separate from our everyday lives – the universe is right above our heads, and beneath our feet. Through our skywatching resources, we hope to help you feel more connected to the astounding wonders that we're exploring in the larger world beyond Earth. And we hope that gazing at the stars above leads you to a more personal connection with our scientific quest to understand our place in the cosmos.