4 min read

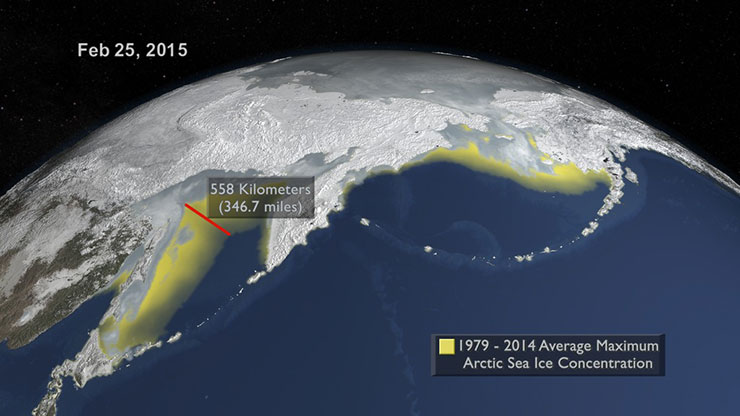

The sea ice cap of the Arctic appeared to reach its annual maximum winter extent on Feb. 25, according to data from the NASA-supported National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) at the University of Colorado, Boulder. At 5.61 million square miles (14.54 million square kilometers), this year’s maximum extent was the smallest on the satellite record and also one of the earliest.

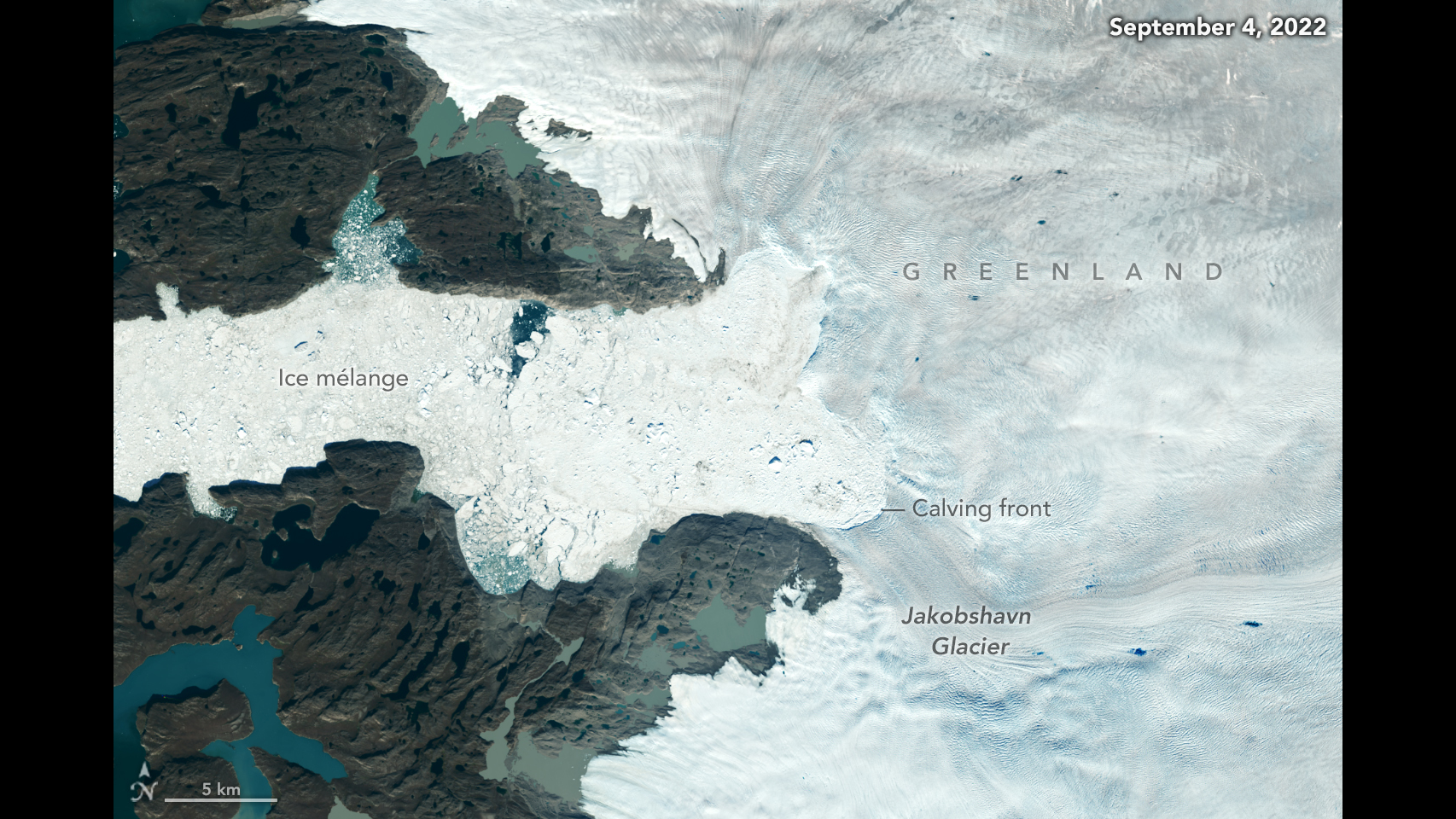

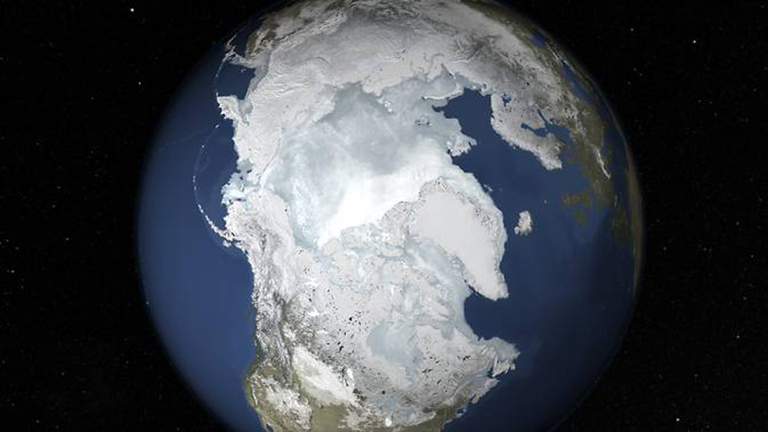

Arctic sea ice, frozen seawater floating on top of the Arctic Ocean and its neighboring seas, is in constant change: it grows in the fall and winter, reaching its annual maximum between late February and early April, and then it shrinks in the spring and summer until it hits its annual minimum extent in September. The past decades have seen a downward trend in Arctic sea ice extent during both the growing and melting season, though the decline is steeper in the latter.

This year’s maximum was reached 15 days earlier than the 1981 to 2010 average date of March 12, according to NSIDC. Only in 1996 did it occur earlier, on Feb. 24. However, the sun is just beginning to rise on the Arctic Ocean and a late spurt of ice growth is still possible, though unlikely.

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. Download this video in HD formats from NASA Goddard's Scientific Visualization Studio.

If the maximum were to remain at 5.61 million square miles, it would be about 50,000 square miles below the previous lowest peak wintertime extent, reached in 2011 at 5.66 million square miles — in percentages, that’s less than a 1 percent difference between the two record low maximums. In comparison, the swings between record lows for the Arctic summertime minimum extent have been much wider: the lowest minimum extent on record, in 2012, was 1.31 million square miles, about 300,000 square miles, or 18.6 percent smaller than the previous record low one, which happened in 2007 and clocked at 1.61 million square miles.

A record low sea ice maximum extent does not necessarily lead to a record low summertime minimum extent.

“The winter maximum gives you a head start, but the minimum is so much more dependent on what happens in the summer that it seems to wash out anything that happens in the winter,” said Walt Meier, a sea ice scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “If the summer is cool, the melt rate will slow down. And the opposite is true, too: even if you start from a fairly high point, warm summer conditions make ice melt fast. This was highlighted by 2012, when we had one of the later maximums on record and extent was near-normal early in the melt season, but still the 2012 minimum was by far the lowest minimum we’ve seen.”

The main player in the wintertime maximum extent is the seasonal ice at the edges of the ice pack. This type of ice is thin and at the mercy of which direction the wind blows: warm winds from the south compact the ice northward and also bring heat that makes the ice melt, while cold winds from the north allow more sea ice to form and spread the ice edge southward.

“Scientifically, the yearly maximum extent is not as interesting as the minimum. It is highly influenced by weather and we’re looking at the loss of thin, seasonal ice that is going to melt anyway in the summer and won’t become part of the permanent ice cover,” Meier said. “With the summertime minimum, when the extent decreases it’s because we’re losing the thick ice component, and that is a better indicator of warming temperatures.”