Nissan’s first fully self-driving car will be based on technology that NASA developed for planetary exploration.

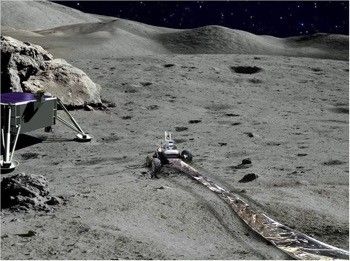

NASA’s Ames Research Center is in the second year of a five-year partnership with Nissan to develop an autonomous electric car, targeted for release in 2020. That collaboration includes adapting software from Ames’ K-10 and K-REX robotic rovers, which were designed to test concepts for future missions such as laying elements for a giant radio telescope on the moon’s far side.

Terry Fong, director of the Intelligent Robotics Group at Ames, leads the NASA team in the self-driving car project. His counterpart is Maarten Sierhuis, director of the Nissan Research Center, Silicon Valley, which is about an eight-minute drive (manual or autonomous) from Ames.

Before coming to Nissan in 2013, Sierhuis spent 12 years as a NASA engineer, working in the same Intelligent Systems Division at Ames as Fong. “Anybody who works at NASA for a long time, you get kind of indoctrinated to believe that there is no problem difficult enough that you cannot solve it,” Sierhuis said.

They have their work cut out for them in perfecting a self-driving car suited to real-world challenges.

Caution: student self-driver

“Frankly, it's pretty easy to address the 80 or 90 percent of things that you see on the road all the time,” Fong said. “What's really hard is addressing the anomalies, things that only pop up once in a while.”

Fong’s daughter came of driving age around the same time the NASA-Nissan collaboration began. His experience in teaching her to drive illustrates one of the chief difficulties in teaching a car to drive itself.

“A tree had fallen halfway across the road, blocking our side of the road,” Fong said. “My daughter said, ‘what do I do?’ And I said, ‘well, let's pull over, look around carefully, and if it's clear, then it's okay for you to drive on the wrong side of the road for a little bit to get around this.’ How do you develop enough intelligence in a self-driving car for the car to make that decision, to recognize that it's okay to break the rules of the road for a short period of time? I frankly have no idea.”

Aside from equipping the car to deal with unusual events, Fong said the toughest part of the task is enabling it to understand and communicate clearly with human drivers, who sometimes forgo turn signals or drive erratically. “When we are still in this world of some cars that are manually driven and some that are autonomous, we are going to have to figure out how we signal between the two,” he said, “until we flip all the way over where everything is autonomous and then we don't have to worry about that anymore.”

“I have a group of anthropologists here that are studying how people behave in traffic,” Sierhuis said. “We use social science to help us understand what people do in the activities of driving, bicycling, being a pedestrian. You need to understand this in order to build a car that can live and behave as a social team member in a society where people move around.”

Faster, smarter, closer

Autonomous cars could free people to spend their commuting time in activities more productive or enjoyable than stewing in traffic jams (see sidebar). Evidence is emerging that robots can drive more safely than people as well. And the environment, too, has a rooting interest in self-driving cars.

It’s easy to see that automated cars can be programmed to drive energy-efficiently, free of jackrabbit starts and seatbelt-straining stops. Less obvious is that a system of self-driving cars could increase the capacity of existing highways, reducing the need to build more.

“Right now, when you are driving on a high-speed freeway, you have to maintain a two-to-four-second gap between the cars, because that's what we humans recognize as being kind of safe in terms of reaction time,” Fong said. “But there's no physical reason why the cars couldn't be closer and all come to a stop safely, especially if they do it in a coordinated fashion. Then you could double or triple the number of cars on the road at any given time. And if they are all working really well, you can also do that at a higher speed.”

“Anybody who works at NASA for a long time, you get kind of indoctrinated to believe that there is no problem difficult enough that you cannot solve it." - Maarten Sierhuis, director of the Nissan Research Center, Silicon Valley

Combining intelligent cars with intelligent traffic-management systems can boost efficiency even further. Sierhuis described using his native Netherlands as a test bed.

“In the region of North Holland, which includes Amsterdam and other big cities, every single traffic light, every bridge is connected,” he said. “The traffic management system knows what's going on. It has all the traffic flow data.

“We have demonstrated that our autonomous vehicle software can communicate bidirectionally with the traffic lights. It can predict whether a traffic light will be green as much as two miles before the car gets to that light. And the vehicle can ask the traffic light for increased green time so it won’t have to stop. If it can't get that green time, it might reroute itself. It's all about making this an efficient system.”

Bumper to bumper spacesuits

“NASA has long had a very safety-oriented culture,” Fong said. “We develop complex systems that we know are operating in difficult environments, so we try to manage the risk and safety associated with operating them. In working with car companies, we've been trying to apply the same kind of approaches.”

Sierhuis agrees, saying that the attitude he brings to his work at Nissan has been transplanted from his work at NASA. “We were developing an intelligent agent for spacesuits,” Sierhuis said, recounting his days as a NASA engineer. He recalls an astronaut telling him, “Maarten, just remember, my spacesuit is my work environment, my home and my life support system. Don’t screw it up. If you screw it up, I’m dead.”

“So I’m thinking, OK, this car is a robot,” Sierhuis said. “It's a freaking heavy robot and it drives 65, 70 miles per hour on the highway and a person is inside of it. And then I think, it's my home, my work environment, my life support. So this is really like the astronaut talking about his spacesuit. We'd better not screw it up.”