In the vast expanse of our solar system, there is one place that, in some ways, we know even better than parts of Earth. It’s a spinning rock that’s a constant throughout our lives: our natural satellite, the Moon.

Around the world, people have found ways to make the Moon their own. The Chinese tell the tale of Chang’e, a Moon goddess. The Ancient Egyptians had the Moon god Khonsu, protector of night-time travelers. The Ancient Greeks had the Moon goddess Selene, who was said to drive a Moon chariot across the dark sky.

Not only have our stories helped us make sense of the Moon, but the Moon has informed our understanding of Earth. So here are 10 things we’ve learned about Earth by studying our closest neighbor.

1. The Makeup of a Newborn Earth

The Moon is not made of cheese; it’s made of remnants of a baby Earth!

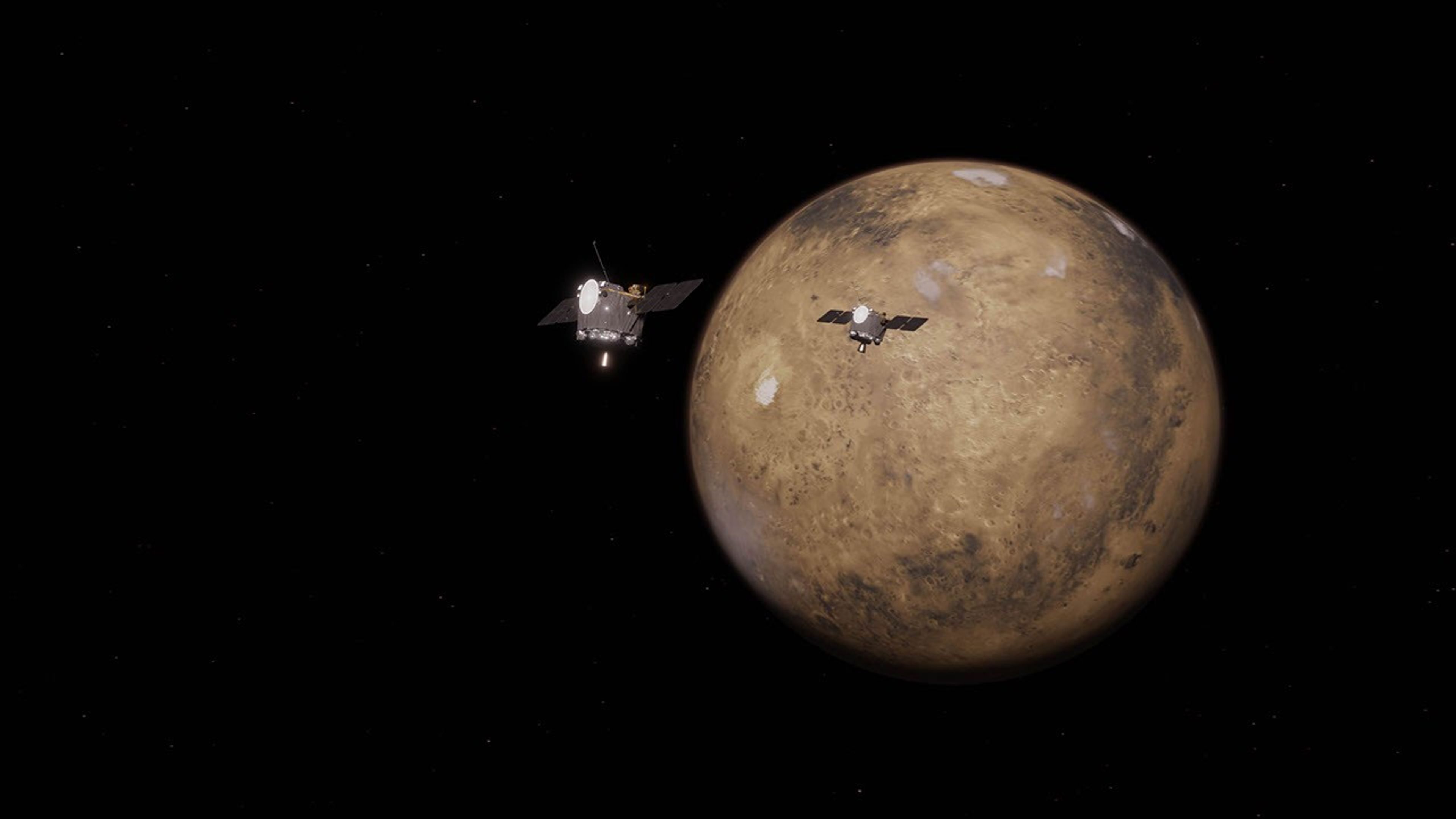

Scientists believe that a Mars-sized object crashed into Earth 4.5 billion years ago. The force of this crash was so great it sent materials from Earth, and from the object that struck it, flying into space. Some of this debris stuck together to make the Moon.

Not only was the Moon constructed largely of Earth, but a lot of debris from Earth probably landed on the Moon in the period after it was formed. More clues about the composition of an early Earth could very well be hidden between layers of Moon dust.

2. Earth's “Time Capsule” on the Moon

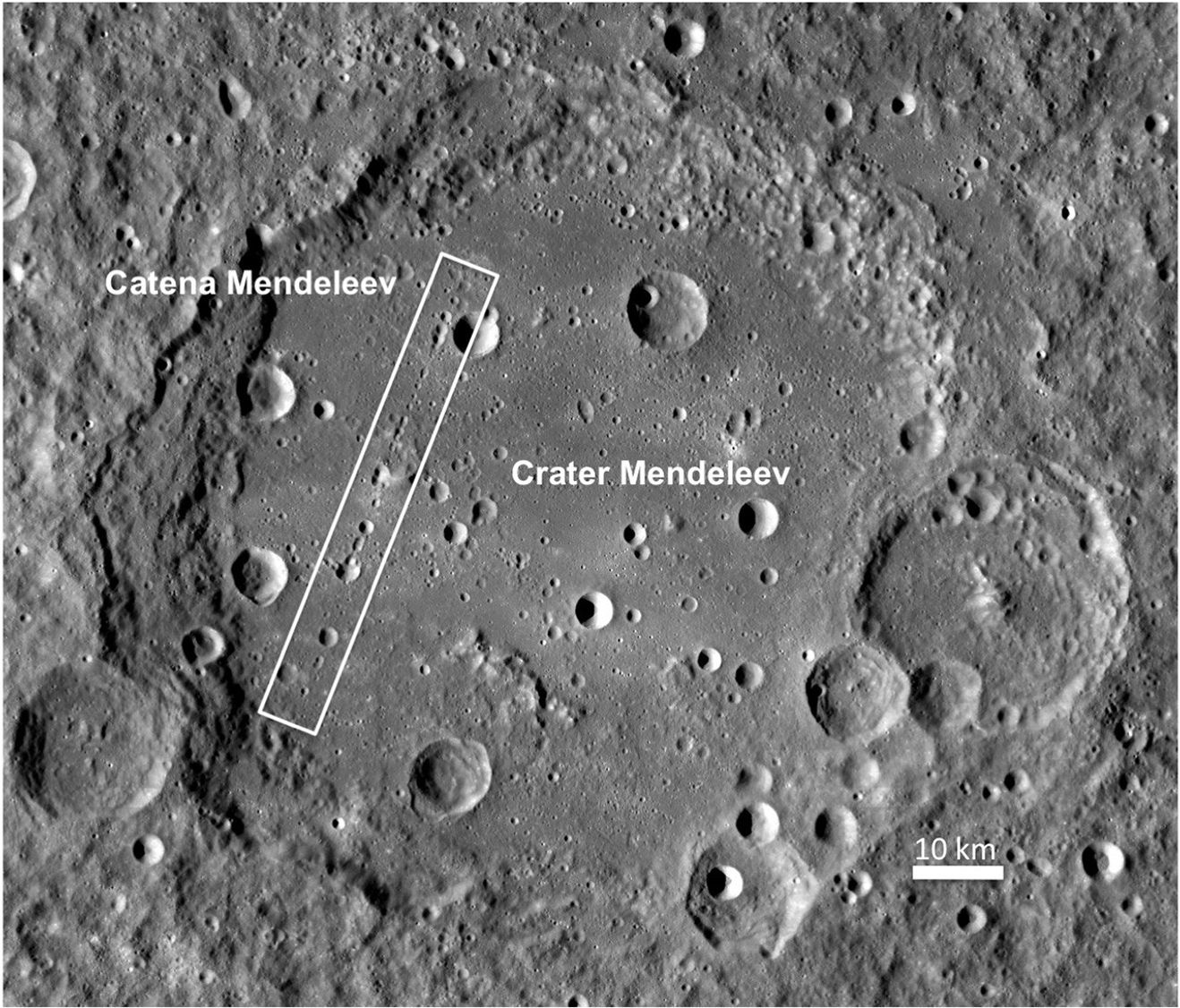

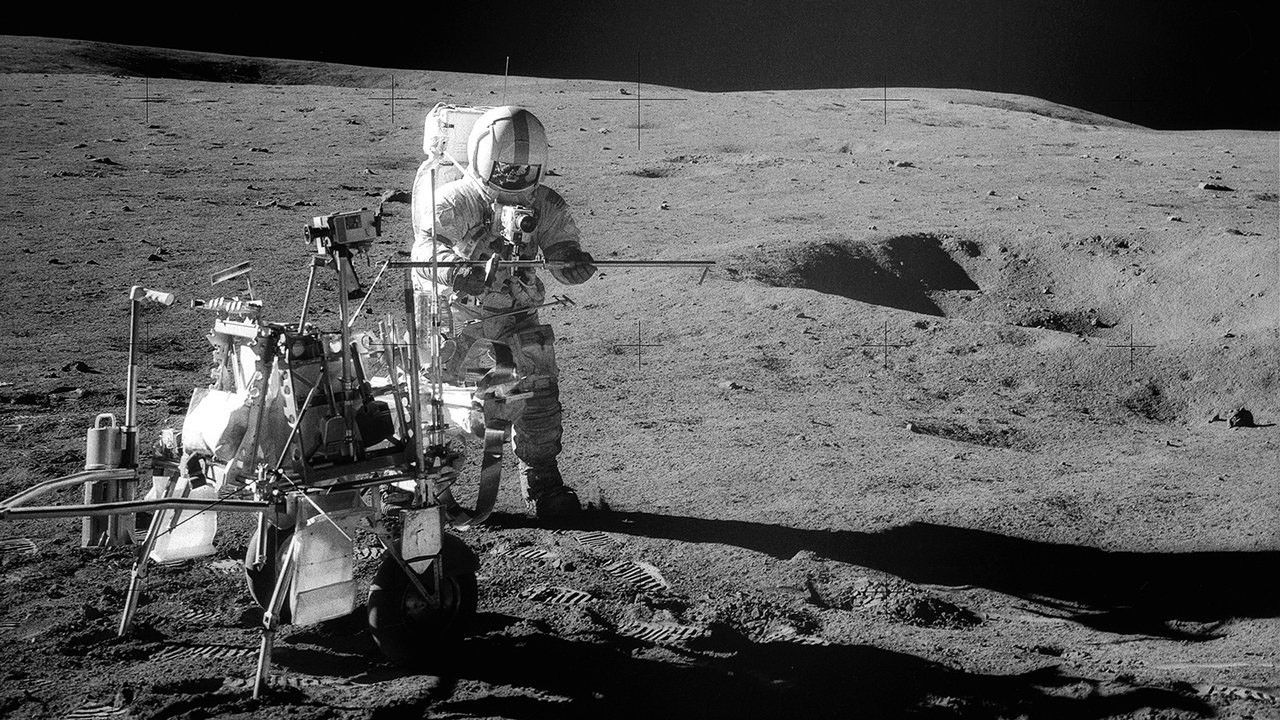

The face of the Moon preserves nearly every crater in its history. Earth, with its surface constantly churned and reshaped by plate tectonics, erosion and other elements, can hardly say the same. But because of how close the Moon is to Earth, we can look to the unchanging lunar surface to uncover Earth’s past. Most Moon craters are thought to have formed about four billion years ago, during a period called the Late Heavy Bombardment. During this time, we believe a huge number of asteroids and other objects pummeled the Moon, our planet and other planets. By studying lunar craters, along with rocks Apollo astronauts brought back decades ago, we have a better picture of what happened to Earth during that turbulent period of time and beyond.

3. Earth Trades “Collectible” Meteorites with the Moon

Rather than playing cards, we think Earth and the Moon trade meteorites. Our studies of the Moon have taught us how meteorites ejected from its surface during asteroid impacts could have fallen to Earth, where they’ve been found by scientists.

These Moon samples come from all areas of the lunar surface, even the far side of the Moon, which we can’t see from Earth. While there is less evidence of stuff from Earth migrating to the Moon, scientists think it’s possible. One study even suggests, based on computer modeling, that there could be approximately 40,000 pounds (20,000 kilograms) of Earth rocks for every 100 square kilometers of the Moon.

4. Potential Clues to How Life Began on Earth

If Earth is, indeed, swapping meteorites with its satellite, these unique relics could tell us more about Earth’s conditions leading up to life.

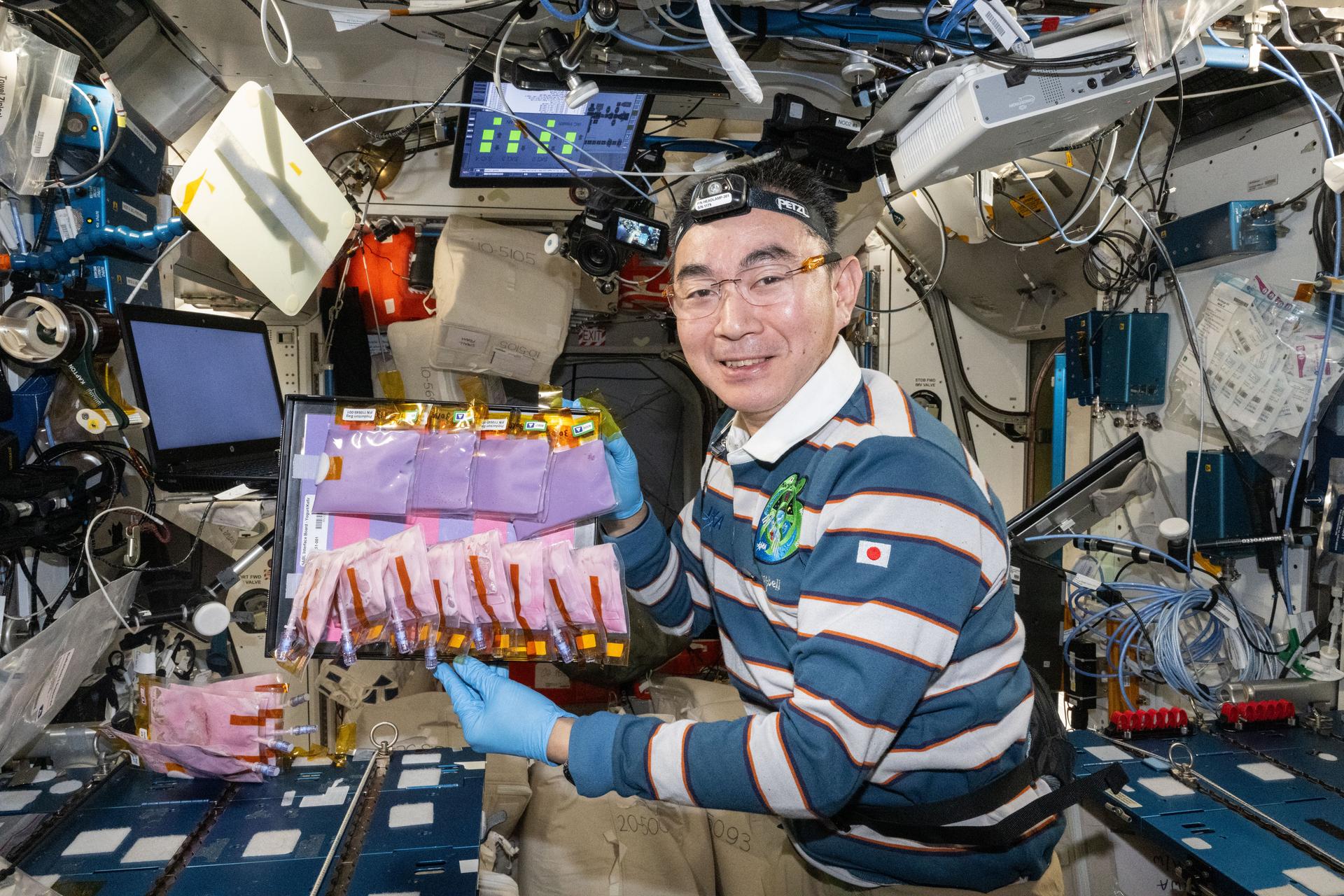

Some scientists have suggested that microorganisms could have existed on the Moon, possibly carried there by meteorites from Earth. Others have also proposed combing through lunar soil for elements, including ancient nitrogen or oxygen, from Earth, which could fill in gaps in knowledge about things like the development of Earth’s atmosphere.

It’s even been suggested that the same materials that brought life to Earth could be preserved in lunar lava.

5. Earth’s Volcanoes are a “Fountain of Youth”

Despite Earth and the Moon having formed around the same time, Earth’s surface looks younger. Our planet’s skin-deep secret? Volcanoes.

Plate tectonics and hot spots continuously help Earth spout rock, ash and gases from its interior. Some of this material settles, thereby renewing Earth’s surface and maintaining its youthful glow.

The Moon has maria, or plains of volcanic rock, that suggest past active volcanoes. Discoveries by NASA’s Lunar Renaissance Orbiter indicate that the Moon could have had volcanic flows up to just tens of millions of years ago, during Earth’s dinosaur age.

Because evidence of lunar volcanic activity has been so well preserved, we can study how it changed through time and under different conditions to better understand volcanic processes on Earth.

6. The Moon May Help Enforce Earth’s Shield

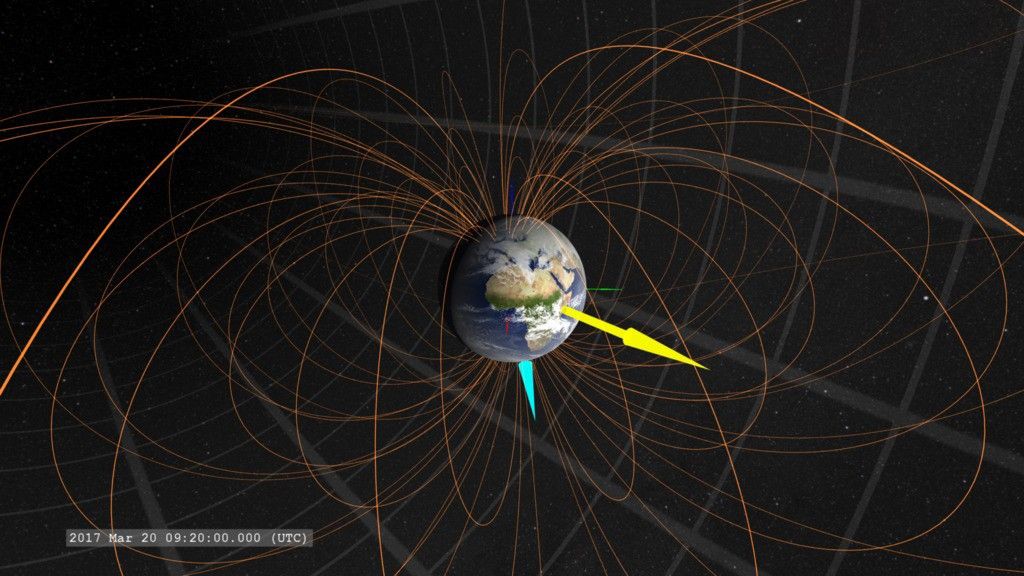

Earth’s magnetic field is our shield, constantly protecting us from harmful solar wind or cosmic ray particles. This important buffer is generated by the fast-flowing movement of liquid iron and nickel in Earth’s outer core

One thing that makes this molten ocean of metal move is the Moon’s gravity. Recent research suggests that the Moon’s gravity tugs on Earth’s mantle layer (which sits on top of the outer core). This causes the liquid, outer core to slosh around, helping to generate the energy needed to maintain our magnetic field.

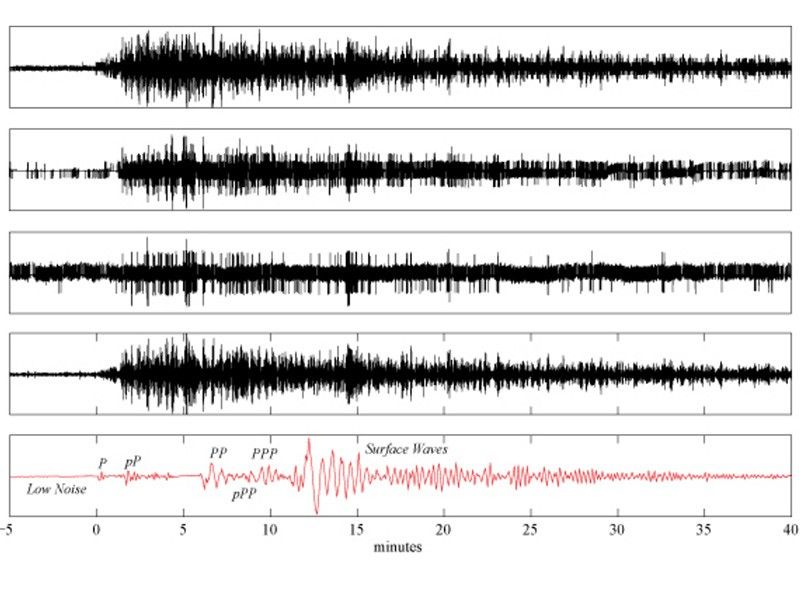

7. Earthquakes are Nothing Like Moonquakes

Earthquakes generally last only half a minute. In contrast, shallow moonquakes, a type of Moon vibration that originates about 12 to 19 miles (20 to 30 kilometers) below the surface, can last at least 10 minutes. The cause of these rare quakes isn’t clear, but they do highlight one reason liquid water is critical on Earth: it helps spread energy out, muffling earthquake vibrations. Studying Moonquakes can help us understand what seismic activity on Earth could have been like during times with less liquid water on the surface, such as during major ice ages or during the Earth's early history, when the surface was much too hot to preserve liquid oceans.

8. Mirror, Mirror on the Moon

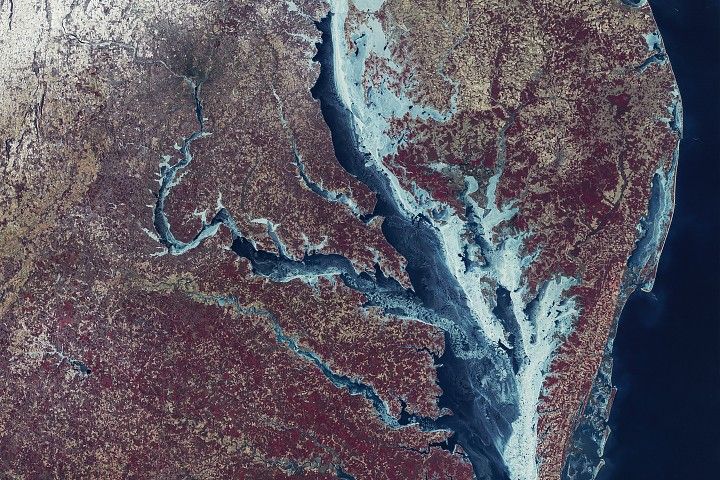

Every planet or moon in our solar system can be measured by its albedo, or how much light it reflects. Think of it as a level of brightness: a brighter body will have higher albedo, while a dimmer body’s albedo will be lower.

On Earth, measuring albedo is especially important because it can help track changes in our climate based on the amount of sunlight Earth absorbs.

The Moon can actually help us measure this key property. Have you ever noticed that during a crescent Moon, you can sometimes faintly see the rest of the Moon's face? This fainter portion of the face is actually lit by sunlight bouncing off of Earth — something called earthshine.

By measuring this glow from the Moon, scientists can accurately estimate how much Earth itself shines, and even the composition of Earth’s atmosphere.

9. The Moon Makes Our Existence Possible…

We have the Moon to thank for our way of life!

Earth’s signature 23.5-degree tilt on its axis is due to the Moon keeping it in check. The 23.5-degree angle ensures our planet is safe to live on, as a more exaggerated tilt would cause more extreme seasons.

Without the Moon’s gravity, Earth would wobble more violently on its axis, drastically altering the climate. Besides maintaining climate stability, the Moon also sets the rhythm of Earth — the highs and lows of our tides — which affects the variety of ways we use the ocean for food, travel and recreation. Precisely measuring the mass, size and orbital properties of the Moon is essential for predicting these rhythms of tides and seasons.

10. ...Yet We’re Pushing It Away

Because Earth and the Moon interact through tides, our planet is actually pushing away its satellite about 1.5 inches (3.78 centimeters) each year — about the same rate fingernails grow. Here’s how: The side of Earth that faces the Moon gets pulled by the Moon’s gravity, creating what scientists call a “tidal bulge,” or a bulge of raised ocean water that’s drawn toward the Moon. Because Earth rotates on its axis faster than the Moon orbits it, the higher gravity from Earth’s bulge tries to speed up the Moon’s rotation. Meanwhile, the Moon is pulling on Earth and slowing the planet’s rotation. The friction that ensues from this tug-of-war forces the Moon into a wider orbit. Studying these tidal and orbital interactions is extremely important for understanding possible effects on Earth's climate.

By Isabelle Yan

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center