5 min read

By Elizabeth Goldbaum,

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

This article is part of a series that explores NASA research into Earth's fresh water and surveys how those advances help people solve real world problems. Learn more.

Snowflakes that cover mountains or linger under tree canopies are a vital freshwater resource for over a billion people around the world. To help determine how much fresh water is stored in snow, a team of NASA-funded researchers is creating a computer-based tool that simulates the best way to detect snow and measure its water content from space.

Snow’s water content, or snow water equivalent (SWE) is a “holy grail for many hydrologists,” said Bart Forman, the project’s principal investigator and a professor with the University of Maryland, College Park. When snow melts, the ensuing puddle of water is its SWE.

In western U.S. states, snow is the main source of drinking water and water from snow is a major contributor to hydroelectric power generation and agriculture.

Some changes in snowfall patterns are indicators of climate change. For instance, warmer temperatures cause water to fall as rain instead of snow. As a result, some mountains are not able to hold water in the form of snowpack like they used to, which means rain inundates rivers and floods are more intense. When flood season is over, droughts can be more severe.

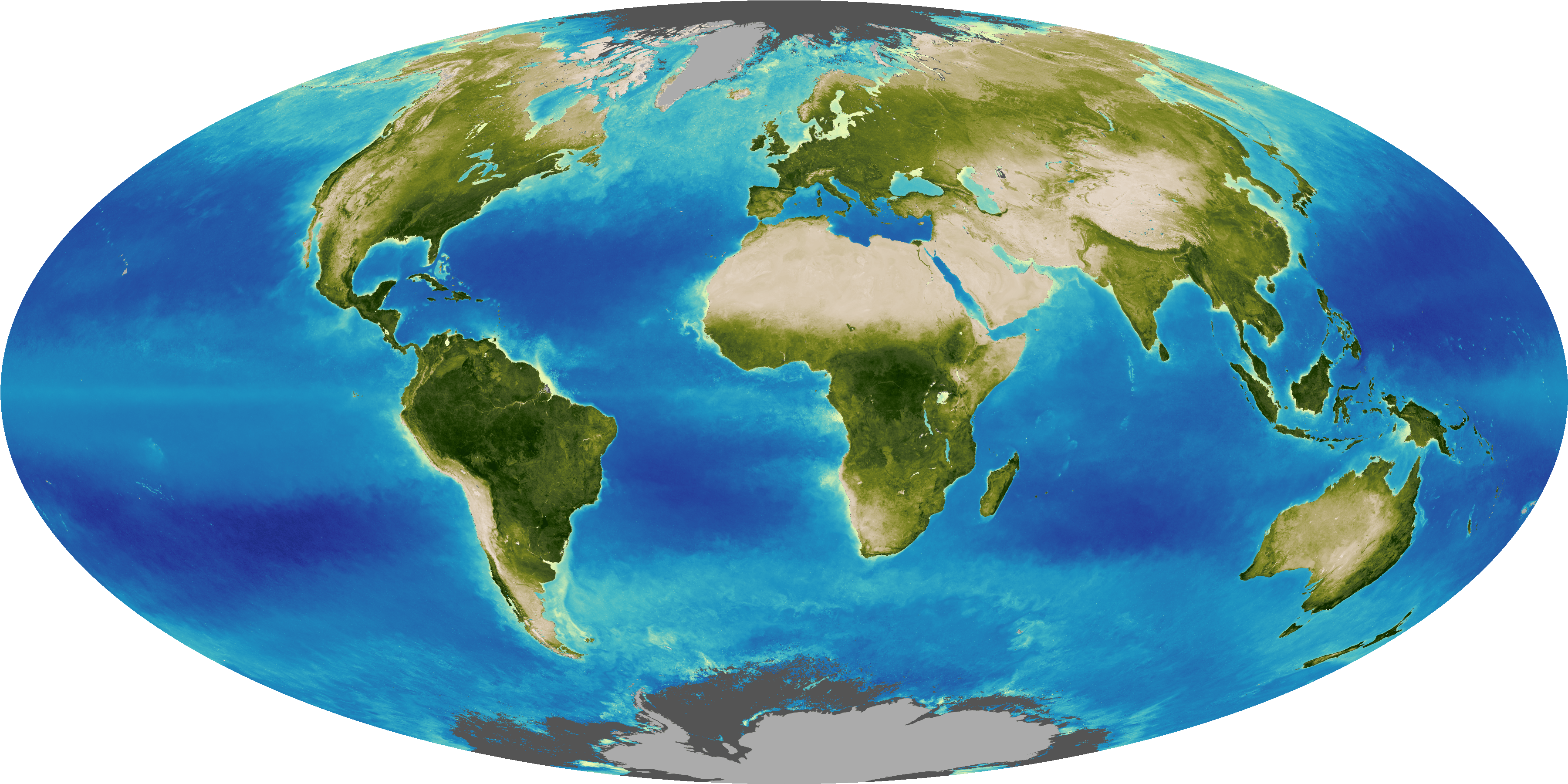

Forman’s new approach follows efforts by NASA to study SWE from satellites, airplanes and the field. The Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) is an instrument aboard two satellites that captures daily images of Earth. MODIS can identify snow-covered land and ice on lakes and large rivers. The Global Precipitation Measurement mission (GPM), an international constellation of satellites, can observe rain and falling snow over the entire globe every two to three hours.

In addition to space-based observations, NASA runs a campaign closer to home called SnowEX. The campaign is a five-year program that includes airborne observations and then field work to reveal what satellite efforts do not. SnowEX allows researchers to examine complex terrains that can be difficult to characterize from space. Next winter’s campaign will collaborate with the Airborne Snow Observatory, which measures snow depth and snow characteristics.

“We would love to have a global map of SWE,” said Edward Kim, a research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. However, there is no single technique that can measure SWE globally because snow properties vary depending on where it lands, Kim said. It often forms a deeper layer in forests, where it is sheltered from the Sun, but keeps a shallower profile in the tundra and prairie, where it is exposed to wind and higher temperatures.

Snow changes its shape as it falls to the surface and then continues to change in its resting place. Its shape can determine which sensor is able to observe it, Kim said, adding another complexity to estimated SWE.

Forman and his team’s new tool will determine the most effective combination of satellite-based sensors to produce the most data. “The tool will show us how to make intelligent choices about how to combine sensors,” Kim said.

The tool evaluates three different types of Earth-orbiting sensors: radar, radiometer and lidar.

The team looked at radar and radiometer information from existing sensors, such as the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer 2 (AMSR2) radiometer. The sensor launched as a partnership led by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to capture microwave emissions from Earth’s surface and atmosphere. It aims to identify snow cover, sea surface temperatures, soil moisture and other factors critical to understanding Earth’s climate.

For radar observations, the team included data from the European Space Agency (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel 1A and 1B satellites, which monitor land and ocean surfaces.

In addition to including radar and radiometer sensors, which are currently monitoring snow from space, the new tool’s simulation includes lidar; lidar has flown aboard airplanes to measure snow over specified areas. For instance, the SnowEx campaign and NASA’s Airborne Snow Observatory use lidar to determine snow depth and SWE. “We can help explore the question, what if we had a snow-centric observing satellite mission in space?” Forman said.

“In order to do all this, you have to use supercomputers,” Forman said. Specifically, the Discover Supercomputer at Goddard and Deepthought2 High-Performance Computing cluster at the University of Maryland.

Once the data from the different sensors are in the simulation tool, the team is able to run experiments that include different scenarios, such as putting a satellite into one orbit versus another, or having a satellite look at a wide swath versus narrow swath of Earth. With this suite of experiments, they can compare how well a certain combination performs compared to a benchmark scenario, Forman said.

As a general rule, with more satellites in orbit, scientists would have higher quality data, Forman said. However, “We can ask, what is the marginal gain if we had one more radiometer?” Forman said.

The new snow-sensing simulation tool will help create a space-based snow observation strategy to better understand this vital freshwater resource. The simulator will be used to “continue to ask questions of what should be next and how we should be planning in 20 years or more,” Forman said.

This new snow simulation tool is funded by NASA’s Earth Science Technology Office.