Searching for planets beyond our solar system takes us out of this world – in fact, high above it.

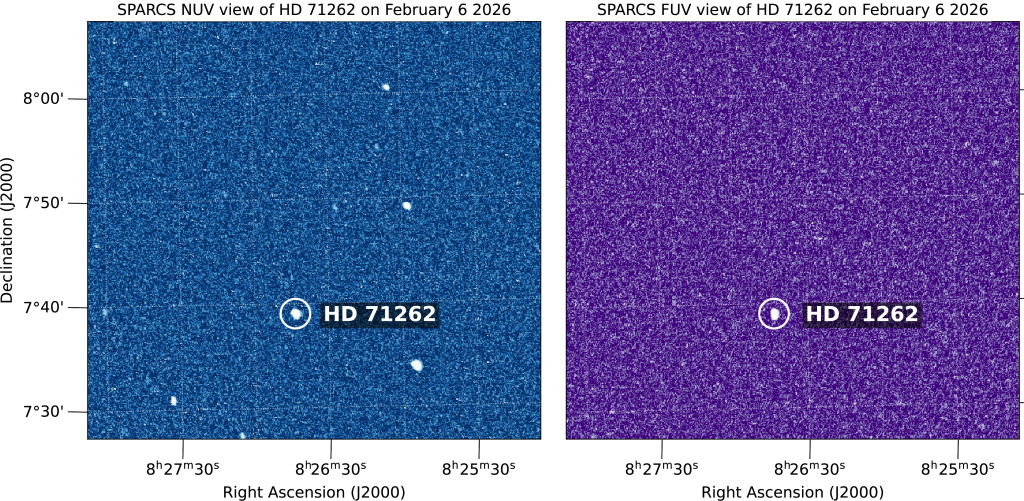

While the first exoplanets – planets around other stars – were discovered using ground-based telescopes, the view was blurry at best. Clouds, moisture, and jittering air molecules all got in the way, limiting what we could learn about these distant worlds.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

To capture finer details – detecting atmospheres on small, rocky planets like Earth, for instance, to seek potential signs of habitability – astronomers knew they needed what we might call “superhero” telescopes, capable of blasting off the surface into orbit.

“While ground-based telescopes showed us that it is indeed possible to discover new planets, it’s often space-based facilities that allow us to advance from initial detections to well-understood worlds,” said Jennifer Burt, an exoplanet scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

Over the past few decades, a team of now-legendary space telescopes answered the call: Hubble, Chandra, Spitzer, Kepler, TESS, and now, the Webb telescope.

Many of their “superpowers,” of course, go far beyond detecting exoplanets. The Hubble Space Telescope can look deep into the cosmic past, seeing light from the early universe and some of the most distant stars and galaxies ever observed. The Chandra X-ray Observatory, like Hubble one of NASA’s “Great Observatories,” examines the universe in X-rays. That has allowed it to peer into the tatters of exploded stars and the edges of our galaxy’s central, supermassive black hole.

Another Great Observatory, the now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope, viewed the cosmos in infrared light, observing structural details of disks around stars and the faint glow of distant galaxies.

All three of these telescopes also have made ground-breaking exoplanet observations.

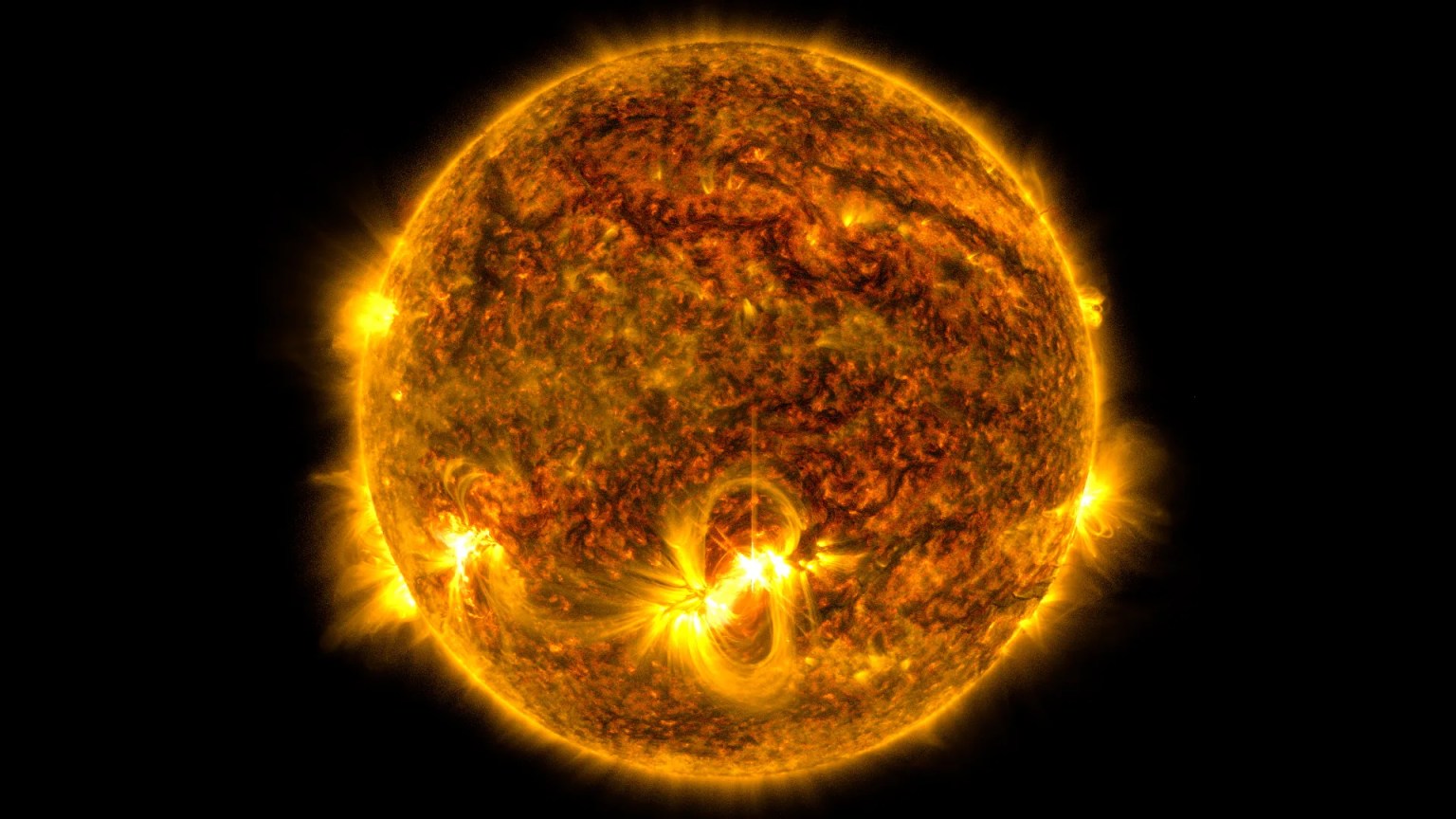

Meanwhile, Kepler, also retired, and TESS took on exoplanets as their main mission, both employing the transit method – searching for tiny dips in starlight as a planet crosses, or “transits,” the face of its star.

The result of all this teamwork: thousands of exoplanets confirmed in our galaxy, and the opening chapter in a new era of discovery – not only finding exoplanets, but understanding what they are like.

Hubble, Spitzer, and Chandra, for example, each helped open the door to analyzing exoplanet atmospheres.

One very strange world, the “hot Jupiter” HD 189733 b, has been observed by all three. Hubble found that the atmosphere of the planet is a deep blue. Spitzer estimated its temperature at 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit (935 degrees Celsius). Chandra, measuring the planet’s transit using X-rays from its star, showed that HD 189733 b’s atmosphere is distended by evaporation.

The James Webb Space Telescope delivered its first images in July 2022, and will also examine the planet, perhaps revealing further details about the composition of its atmosphere.

And Webb will open the door to atmospheric characterization even farther, probing the seven Earth-sized worlds orbiting a star called TRAPPIST-1 and seeking evidence of atmospheric gases.

If Webb succeeds, it will mark the first detection of an atmosphere around a rocky, Earth-sized planet.

Call it epic, or even heroic: The space telescope adventure continues.