When it comes to coal, perhaps the only thing more controversial than what to do about the heat-trapping carbon dioxide it generates is what to do about the social and environmental costs of getting it out of the ground. Nowhere is the debate over how far we are willing to go for inexpensive energy more contentious than in the coalfields of the Appalachian Mountains, where technology and engineering have allowed the scale of surface coal mines to reach gigantic proportions.

The most controversial mines are known as mountaintop removal mines because coal companies literally remove the tops of mountains with dynamite and earth-moving machines, called draglines, in order to reach coal seams. The waste rock—the remains of the mountains—is piled into neighboring hollows in towering earthen dams called valley fills. The largest fills can approach 800 feet in height and swallow more than a mile of streambed. In southern West Virginia, where the practice is most widespread, some of these behemoth mines are several thousand acres and still growing.

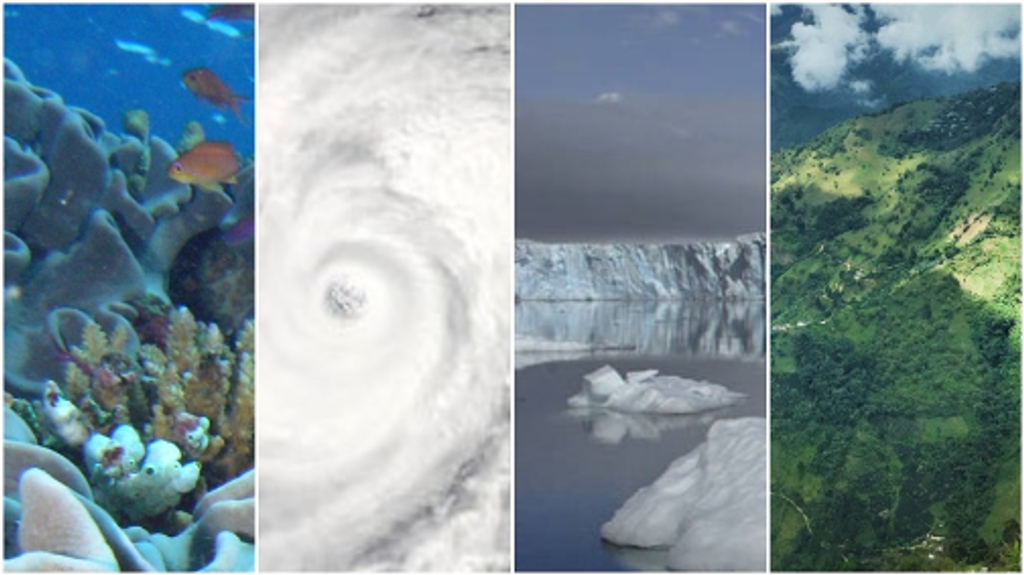

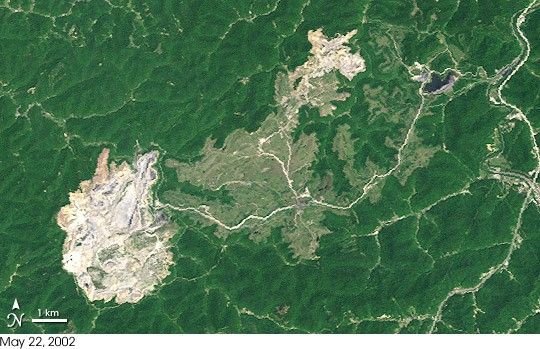

Before and After

Hobet-21 mountaintop mine in the Mud River watershed of West Virginia

June 6, 1987 – May 2, 2002

The scale of these mines is matched by the social and environmental problems they create. Downstream of mountaintop removal and valley fill sites, water quality and stream life are often degraded. Water, streambed sediments, and fish tissue often harbor concentrations of potentially toxic trace elements, including nickel, lead, cadmium, iron, and selenium, that exceed government standards. The diversity of fish and other aquatic life declines. Hundreds of thousands of acres of some of the world’s most biologically diverse forests outside of the tropics have been lost or degraded, and, to date, efforts to restore them have had limited success. Valley fills have worsened flash flooding during heavy rain events. Blasting has cracked house foundations. Floods from the collapse of valley fills and coal sludge impoundments, though rare, have devastated some watersheds and communities.

Since the late 1990s, environmental groups and coalfield residents have brought lawsuits against coal operators and regulatory agencies over these mines. Using streams as a landfill for mining waste is illegal under the Clean Water Act, they argue, and the flattened ridge lines and valley fills are a violation of the core requirement of the 1977 Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act: that mining companies restore the land to its original shape—the “approximate original contour”—as best they can. Variances could be granted if the coal operator offered specific plans for post-mining development that would benefit the community, such as schools, housing, or shopping centers, but in most cases, the development never materialized.

In West Virginia, the rise in lawsuits created a demand for a state-wide accounting of the impact of mountaintop removal mines, which the agencies responsible for regulating them—the federal Office of Surface Mining, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection—could not initially provide. They couldn’t say conclusively say how many mountaintop removal mines existed, how many streams had been buried by valley fills, how many “approximate original contour” variances had been granted, or whether the promised reclamation and development had actually occurred.

As part of a settlement of a 1998 lawsuit over a mountaintop removal mine near Blair, West Virginia, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency agreed to conduct an environmental impact study on the cumulative impact of mountaintop removal mining, which it published in 2005. In the roughly 12-million-acre region of eastern Kentucky, southern West Virginia, western Virginia, and eastern Tennessee where mountaintop removal mining takes place, nearly 7 percent of the land had been or would be disturbed by mountaintop removal mines between 1992-2012. More than 1,200 miles of streams had been degraded by mountaintop removal mining. At least 724 miles of streams were completely buried by valley fills between 1985 and 2001. Permits issued since then will affect thousands of additional acres and hundreds of miles of streams.

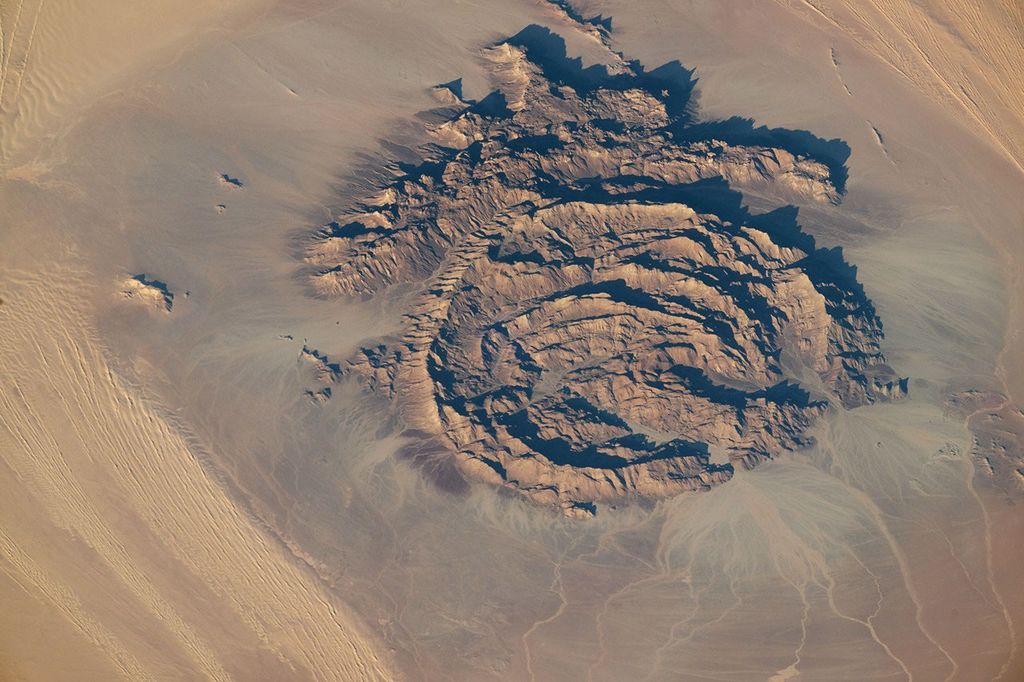

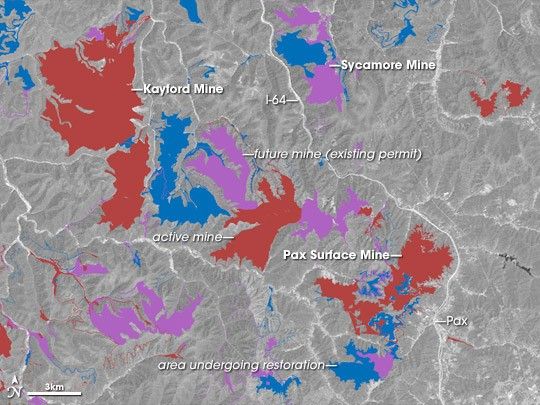

Mine permits in southwest West Virginia

May 22, 2002

Surface mining at these scales is more economical for coal companies, safer for miners, and, coal operators say, essential for mining the thin seams of lower-sulfur coal more valuable in today’s market. With dynamite and immense machines, surface mines can produce more than two to three times as much coal per miner as underground mines can.

Although employment in the coal industry has declined over the past half-century, mining remains the backbone of West Virginia’s economy. Coalfield residents argue bitterly over whether some people’s jobs are more important than other people’s homes or the preservation of the area’s natural heritage. This natural heritage is part of the area’s rural culture, and it draws millions of tourists each year.

As courts try to determine how existing environmental statutes apply to mountaintop removal operations, the regulatory framework is shifting. In 2004, the federal Office of Surface Mining announced plans to re-write the “buffer zone” rule that prohibits most mining activities within 100 feet of a stream to make it clear that valley fills in streams were permissible, but subject to regulation. In May 2007, 50 members of the U.S. House of Representatives responded to the proposal by co-sponsoring legislation that would prohibit disposing of mine waste in streams. Meanwhile, citizen lawsuits against coal operators and state and federal regulators continue to work their way through the courts.

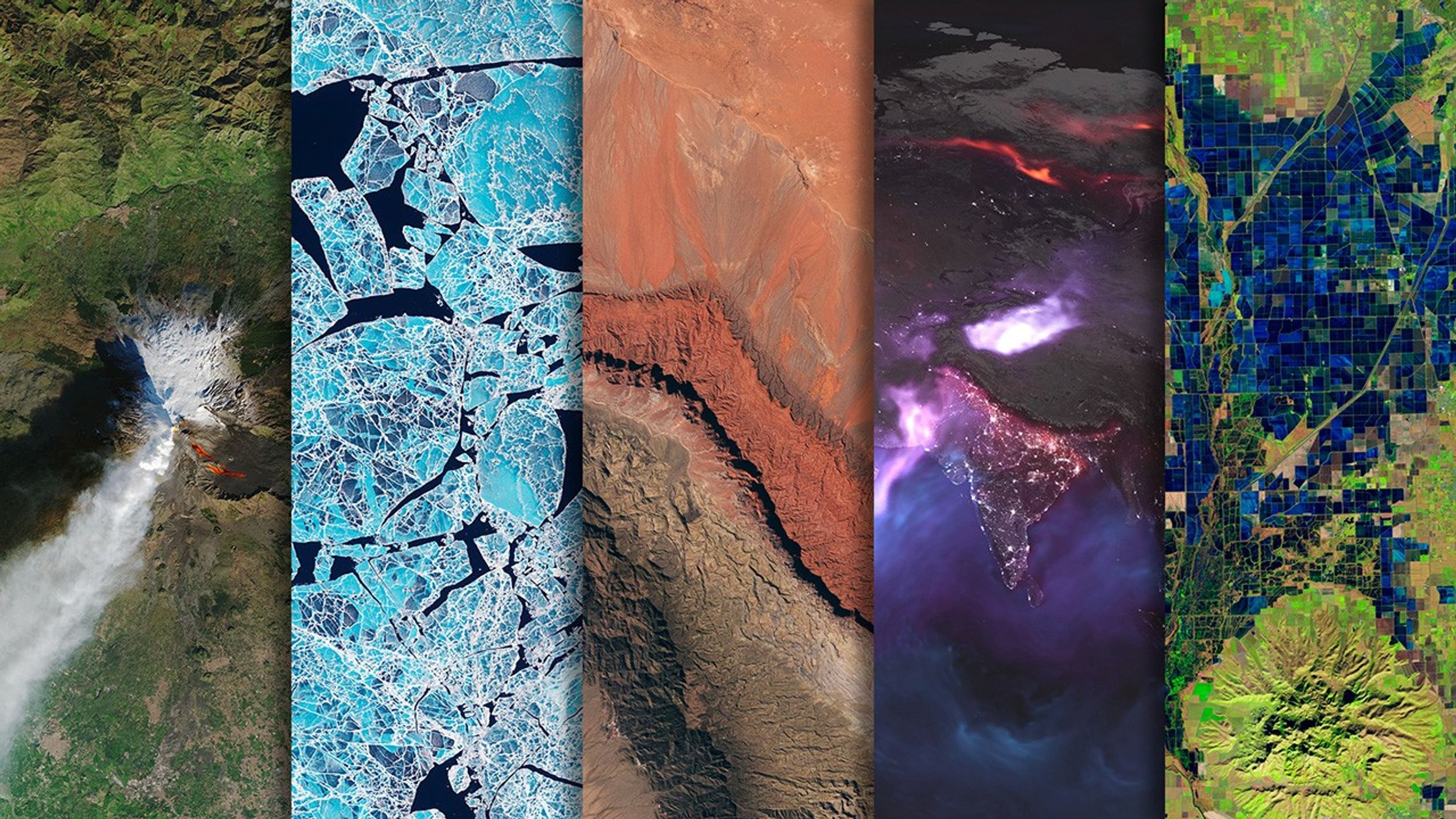

How these conflicting legislative and judicial issues will be resolved remains uncertain. In the meantime, remote-sensing data and images can be valuable tools for scientists, policymakers, and citizens who are interested in understanding and visualizing the widespread impact of this type of mining on the Appalachian landscape

References

- American Geophysical Institute (2003, October 20). Settlement reached on coal slurry spill. Geotimes.org. Accessed December 20, 2007.

- Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition. Massey Valley Fill Disaster, Lyburn, WV. Accessed December 20, 2007.

- GovTrack.us. (2007). H.R. 2169–110th Congress. Clean Water Protection Act. GovTrack.us Database of Federal legislation. Accessed Dec 16, 2007.

- Ryan, B. (2007, October 18). Judge grants injunction on mining permit. The State Journal. Accessed December 20, 2007.

- U.S. Department of the Interior Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement. (2004, January 7). Surface Coal Mining and Reclamation Operations; Excess Spoil; Stream Buffer Zones; Diversions; Proposed Rule Federal Register, 69(4).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2005). Mountaintop Mining/Valley Fills in Appalachia: Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement. Accessed December 20, 2007.

- Ward, K. (2007, August 22). OSM proposes exempting fills from buffer zone rule. Charleston Gazette-Mail. Accessed December 20, 2007.

- Ward, K. (1998, August 9). Flattened: Most mountaintop mines left as pasture land in state. Charleston Gazette-Mail. Accessed December 20, 2007.

- Ward, K. (1998, August 9). Number of mines in state is unknown. Charleston Gazette-Mail. Accessed December 20, 2007.

- Ward, K. (2007, July 22). 30 years later, mine law’s success debated. Charleston Gazette-Mail. Accessed December 20, 2007.

- West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection Division of Mining and Reclamation. Findings of the Flood Advisory Technical Task Force. Accessed December 20, 2007.

NASA Earth Observatory story by Rebecca Lindsey, design by Robert Simmon