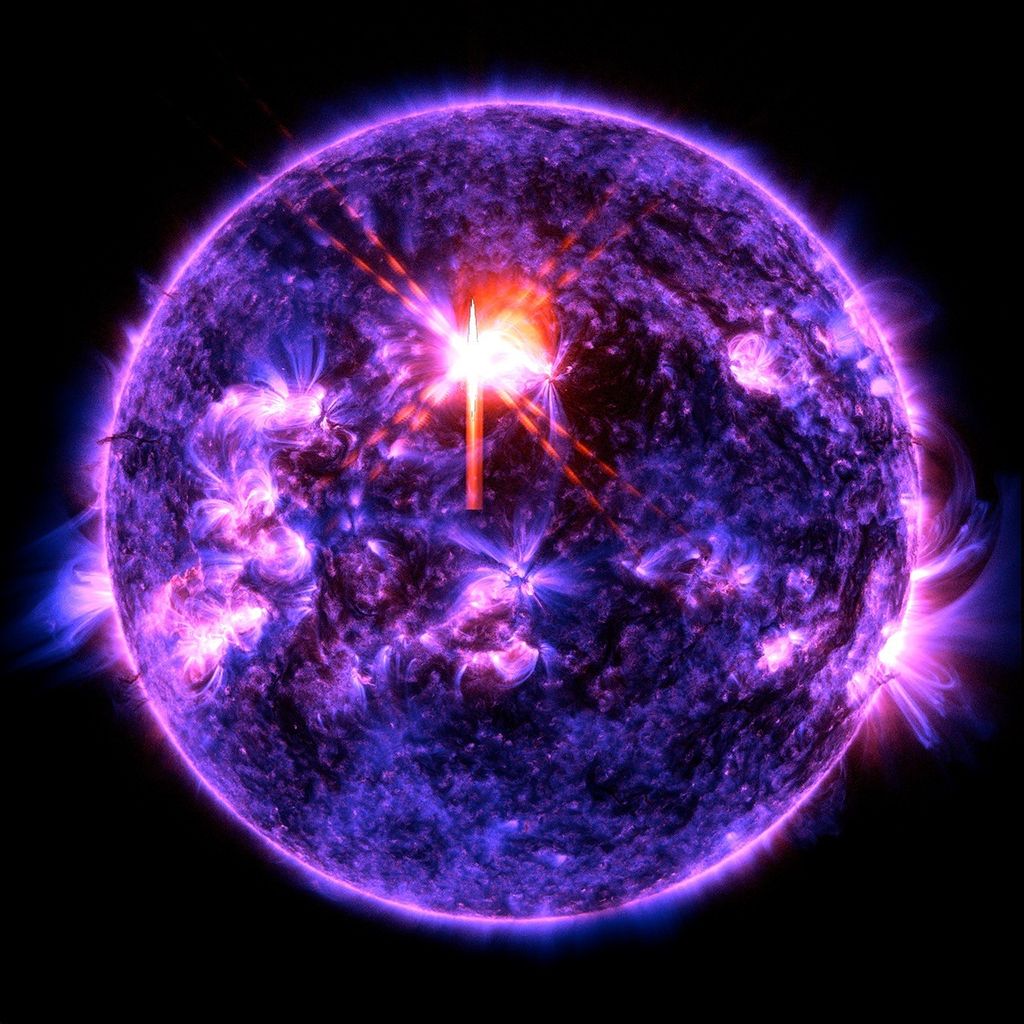

Driven by a need for fresh produce and drinking water, the United Statesnow utilizes as much as 90 percent of the water that flows into theColorado River. As a result, very little of the Colorado River nowreaches the Colorado River Delta. Many environmentalists and scientistsalike fear the natural ecosystem in the delta may be beyond repair.Yet, no one really knows what the ecosystem in the delta was like beforeits initial decline in the early 20th century. In order to unravel thedelta's past, one group of researchers at the University of Arizona hasbeen using images much like the one above to locate and study old clamshells in the delta. By examining these shells, the researchers believethey can determine how abundant marine life was around the ColoradoRiver Delta when the waters of the Colorado River flowed freely.

The above image of the lower eastern section of the Colorado River Deltawas taken on September 8, 2000, by the Advanced Spaceborne ThermalEmission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) flying aboard NASA's Terraspacecraft. The Colorado River comes to an end just north and east ofthis image in Baja, California. The far northwestern shore of the Gulfof California can be seen in blue on the right hand side of the image.The gray expanse bordering the gulf are mud flats formed by sedimentsdeposited over hundreds of years by the Colorado River. The large whitepatches to the left of the mud flats are highly reflective salt pans.Piles of dead shells accumulate along the southeastern portion of themud flats. They make up ivory-colored beaches and mostly lie along theborder between the gulf and the mud flats.

Karl Flessa, a paleontologist at the University of Arizona, explainsthat the appearance of these clamshell "islands" themselves is due tothe damming and draining of the Colorado River. Most of the sedimentsthat the Colorado River picks up as it moves through the AmericanSouthwest are now captured behind the Hoover Dam or the Glen Canyon Damwell before they reach the river delta. Without a steady supply ofsediments, the mud flats have been slowly eaten away by the waters ofthe Gulf of California. Each day as the tide moves back and forthacross the flats, the waters remove small sediments and expose oldclamshells.

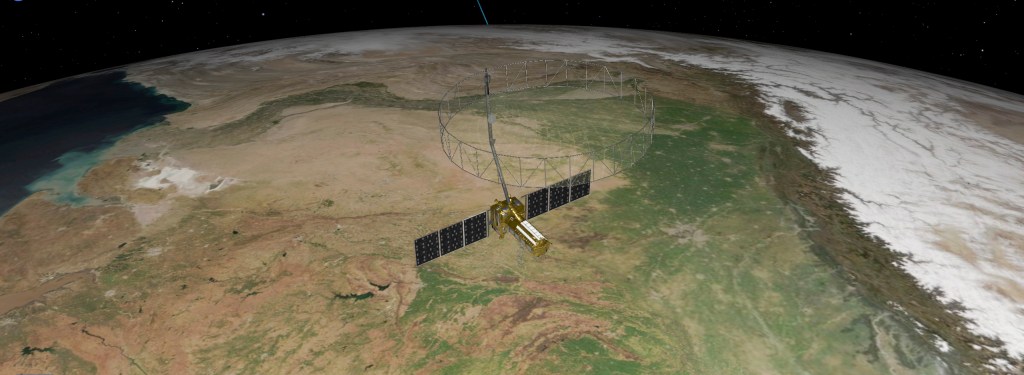

Flessa and his group are studying the clamshell "islands" to learn moreabout what the environment was like when the river flowed into the gulf.They employ Landsat 7 images much like the image shown above to locateold clam beds and find their way around the mudflats. Once there, Flessaexplains he and his team scoop up large samples of shells and take themto a lab. By then isolating certain radioisotopes found in the shells,the scientists can determine how abundant clam shells were in the pastand compare them to present day populations.

What the scientists have uncovered so far is that over the past centurythe number of living clams in the delta has decreased by 95 percent.Flessa explains that the reduction of clams is due to the increasedsalinity and lower nutrients in the delta region. Most of the clamsthat lived in the delta thrived in a salt water/fresh water mix. Whenthe river stopped flowing into the gulf, the waters became briny and theclams died. Since the clams were near the bottom of the food chain,it's likely that a large portion of the larger animals in the regionvanished as well.

For more information about the Colorado River Delta, see the image from March 26, 2001

References & Resources

Image courtesy NASA/GSFC/MITI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team