Mariner 9

Type

Launch

Target

entered mars orbit

What was Mariner 9?

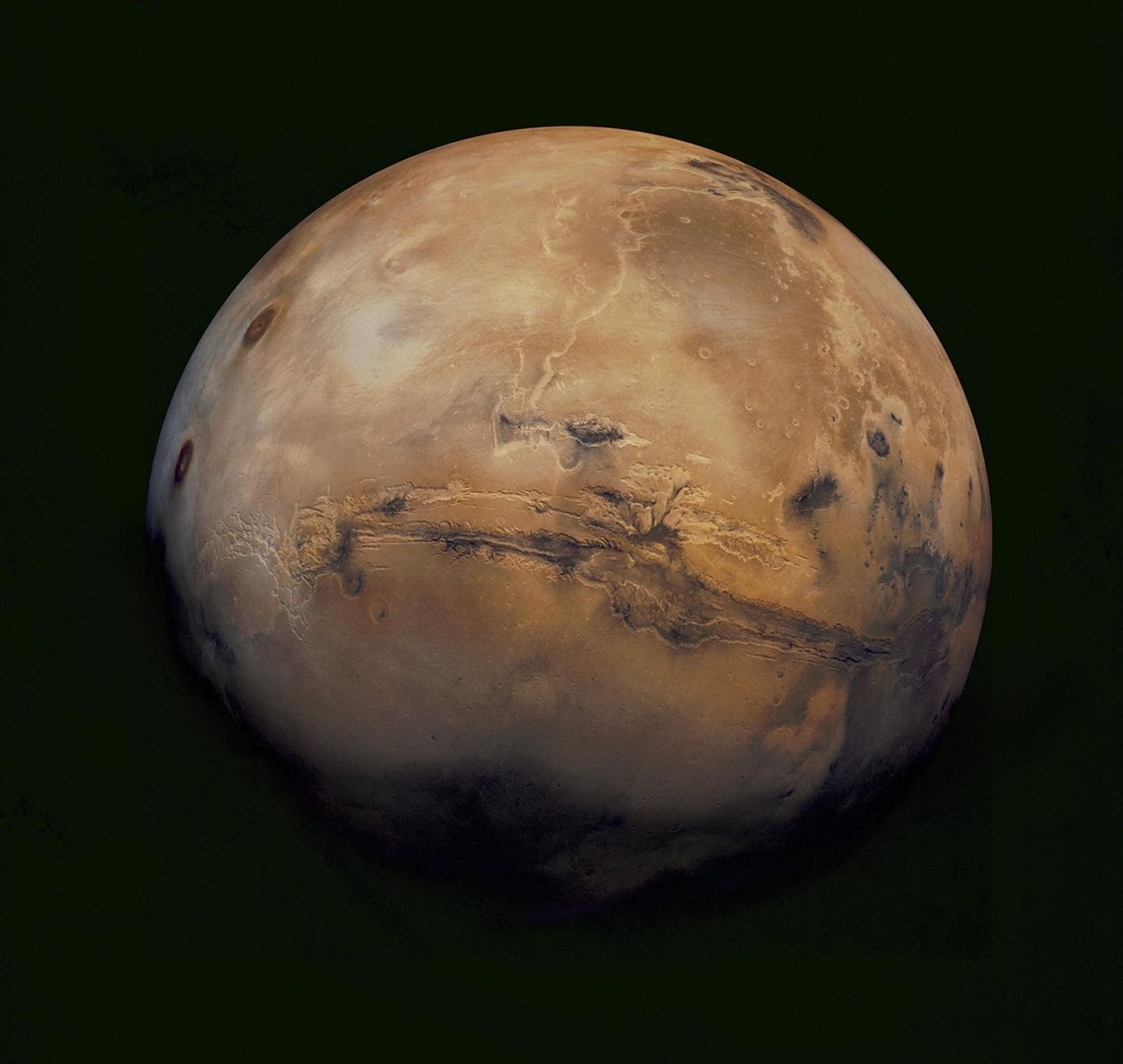

NASA's Mariner 9 was the first spacecraft to orbit another planet, when it beat the Soviet Mars 2—which had an 11-day head start—to the Red Planet. Mariner 9 mapped 85% of the Martian surface and sent back more than 7,000 pictures, including images of Olympus Mons, Valles Marineris, and the moons Phobos and Deimos.

| Nation | United States of America (USA) |

| Objective(s) | Mars Orbit |

| Spacecraft | Mariner-71I / Mariner-I |

| Spacecraft Mass | 2,200 pounds (997.9 kilograms) |

| Spacecraft Power | Solar |

| Mission Design and Management | NASA / JPL |

| Launch Vehicle | Atlas Centaur (AC-23 / Atlas 3C no. 5404C / Centaur D-1A) |

| Launch Date and Time | May 30, 1971 / 22:23:04 UT |

| Launch Site | Cape Canaveral, Fla. / Launch Complex 36B |

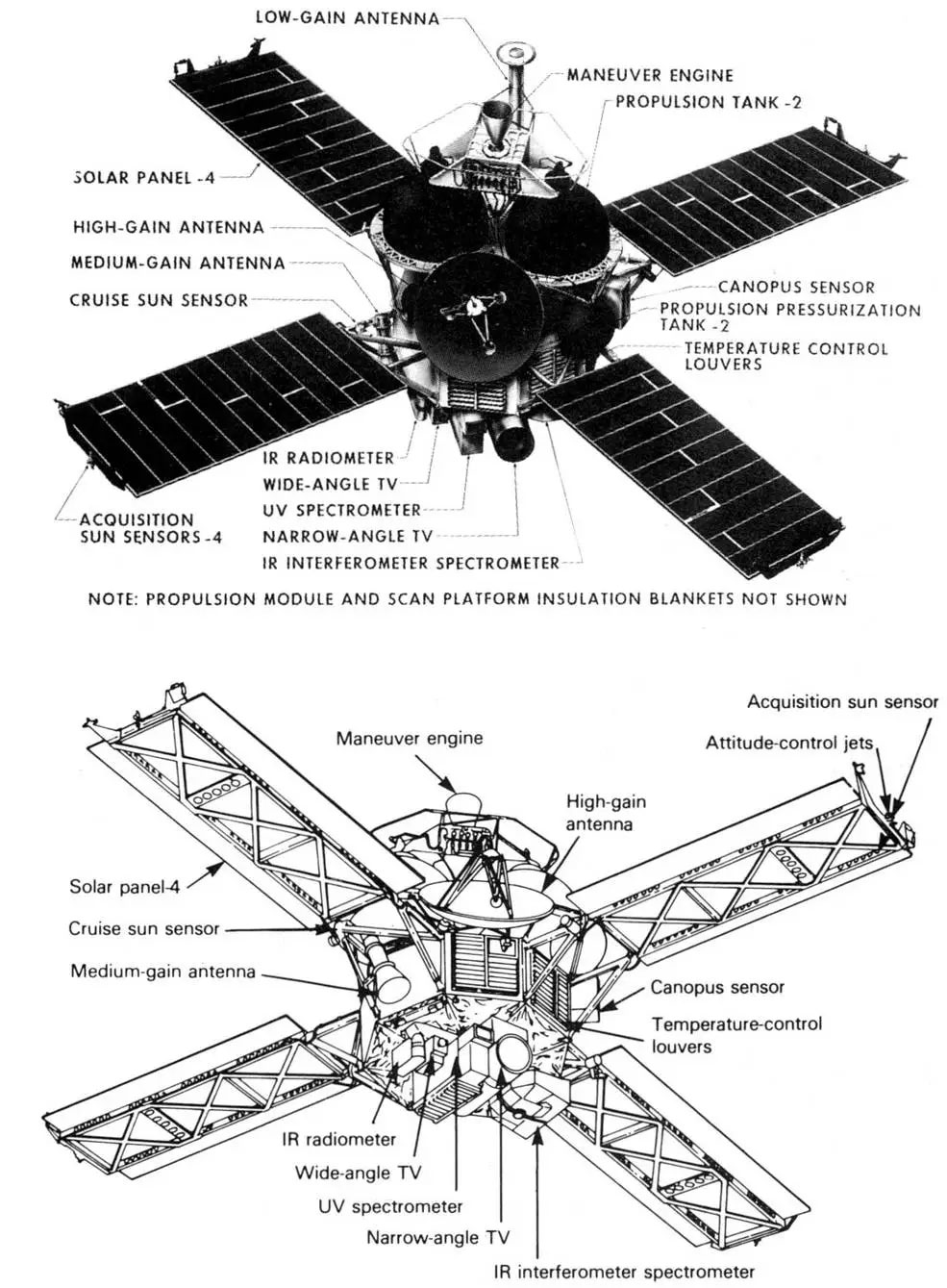

| Scientific Instruments | 1. Imaging System 2. Ultraviolet Spectrometer 3. Infrared Spectrometer 4. Infrared Radiometer |

Results

Mariner 9, the second in a pair of identical NASA Mars orbiters, lifted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, at 22:23:04 May 30, 1971. The successful launch came just days after Mariner 8 failed to reach Earth orbit after launch May 9.

All scientific instruments on Mariner 9 were mounted on a movable scan platform underneath the main body. The spacecraft spanned about 22 feet (6.9 meters) including its extended solar panels.

At 00:18 UT Nov. 14, 1971, Mariner 9 ignited its main engine for 915.6 seconds to become the first human-made object to enter orbit around another planet.

Initial orbital parameters were about 870 × 11,130 miles (1,398 × 17,916 kilometers) at a 64.3-degree inclination. Another firing on the fourth revolution around Mars refined the orbit to about 870 × 10,650 miles (1,394 × 17,144 kilometers) at 64.34-degrees inclination.

The primary goal of the mission was to map about 70% of the surface during the first three months of operation. The dedicated imaging mission began in late November, but because of a major dust storm, photos of the planet taken prior to about mid-January 1972 did not show great detail.

Once the dust storm subsided, starting Jan. 2, 1972, Mariner 9 began to return spectacular photos of the deeply pitted Martian landscape, for the first time showing such features as the great system of parallel rilles stretching more than 1,100 miles (1,700 kilometers) across Mare Sirenum.

The vast amount of incoming data countered the notion that Mars was geologically inert.

There was some speculation about the possibility of water having existed on the surface during an earlier period, but the spacecraft data could not provide any conclusive proof.

By February 1972, the spacecraft had identified about 20 volcanoes, one of which was later named Olympus Mons.

Based on data from Mariner 9’s spectrometers, it was determined that Olympus Mons, part of Nix Olympica—a “great volcanic pile” possibly formed by the eruption of hot magma from the planet’s interior—is about 9 to 19 miles (15 to 30 kilometers) tall and has a base with a diameter of 370 miles (600 kilometers). It dwarfs all volcanoes on Earth.

Another major surface feature identified was Valles Marineris, a system of canyons east of the Tharsis region that is more than 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers) long, 120 miles (200 kilometers) wide, and in some areas, more than 4 miles (7 kilometers) deep. The canyon was named in honor of Mariner 9.

On Feb. 11, 1972, NASA announced that Mariner 9 had achieved all its goals, although the spacecraft continued sending back useful data well into the summer.

By the time of last contact at 22:32 UT Oct. 27, 1972, when it exhausted gaseous nitrogen for attitude control, the spacecraft had mapped 85% of the planet at a resolution of 0.5 to 1 mile (1 to 2 kilometers), returning 7,329 photos, including at least 80 photos of Phobos and Deimos.

Thus ended one of the great early robotic missions of the space age and undoubtedly one of the most influential. The spacecraft is expected to crash onto the Martian surface sometime around 2020.