Cutting 363 miles (584 kilometers) across the state of New York, the Erie Canal was the engineering marvel of its day when it opened in 1825. The waterway was built over 8 years through the toil of humans and animals, new tools and techniques, and plenty of ingenuity. It established a navigable route from Lake Erie to the Hudson River, forming a vital connection between the U.S. Midwest and the Atlantic Ocean.

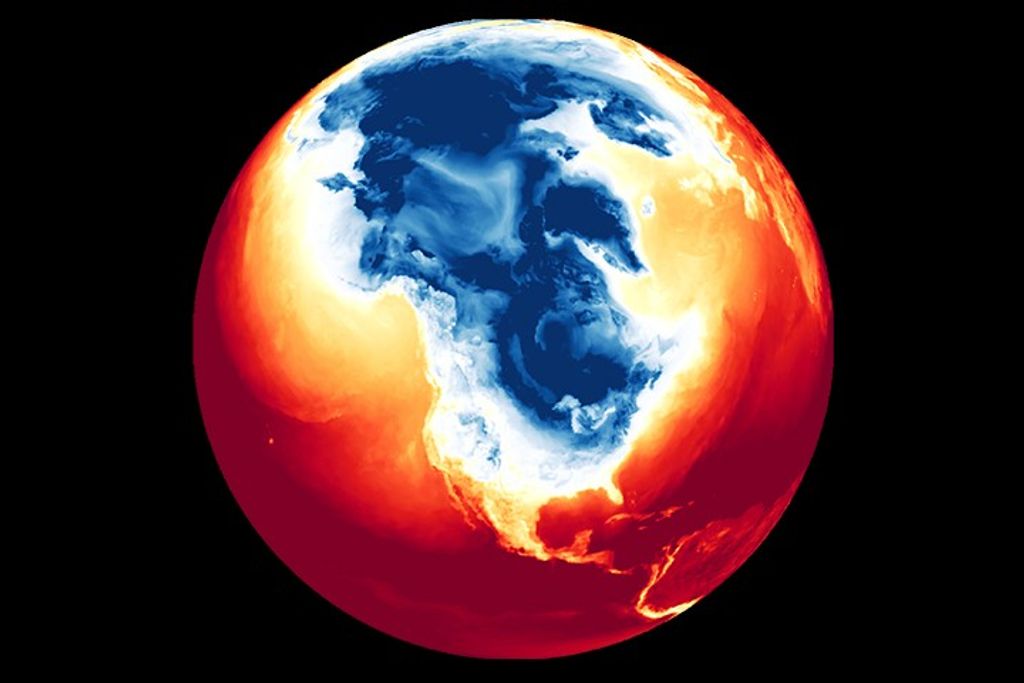

This image shows the modern path of the Erie Canal. The path is overlaid on a Blue Marble: Next Generation image built from scenes captured by the MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer). The canal’s western half roughly parallels the shores of Lake Ontario, while to the east, the route follows the Mohawk River valley’s natural divide between the Catskill and Adirondack mountains. The waterway cuts through northern hardwood and oak-hickory forests, as well as wetlands such as Montezuma Marsh in the Finger Lakes region.

There were no engineering schools in the U.S. at the time of the canal’s inception, but the amateurs who guided its design and construction would become known as graduates of the “Erie School of Engineering.” These engineers devised contraptions for tree felling and stump removal, implements for digging the waterway to its standard dimensions—4 feet deep and 40 feet wide—and techniques for blasting through rock.

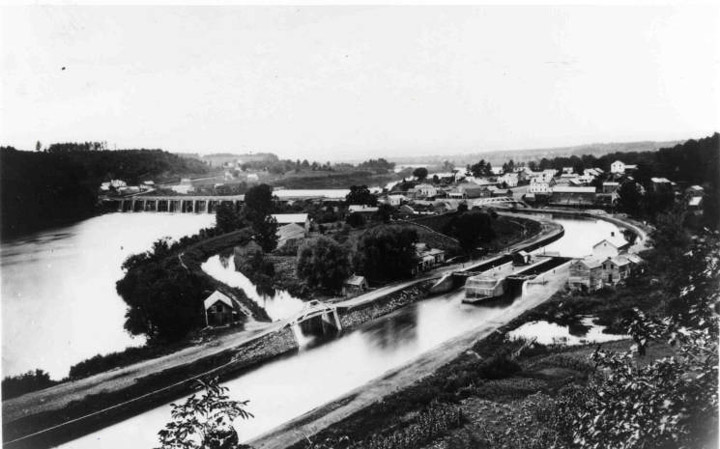

Other achievements included the construction of 83 locks, including a series of “steps” to raise boats over the Niagara Escarpment at Lockport, and several aqueducts to bypass rivers and streams. The photo below, taken around 1880, shows an aqueduct over the Mohawk River about 15 miles (24 kilometers) northwest of Albany.

The canal’s opening had immediate effects. With transport times drastically shorter than alternatives, barge after barge of goods and materials were towed through by horse or mule. Packet boats carried passengers from Albany to Buffalo in five days, rather than the two weeks it took by stagecoach. Tolls paid back the construction costs within 10 years.

Cities also burgeoned along the route. In 1820, before the canal, Rochester and Syracuse were small settlements not yet incorporated as cities, and Buffalo and Utica had populations of less than 3,000. By 1850, all four were among the top 40 most populous cities in the U.S.

The Erie Canal itself expanded and evolved until other routes and modes of transport eventually supplanted it. Several enlargements allowed larger vessels and heavier loads to pass through. All the while, railroads increasingly transported more cargo. Commercial traffic on New York’s canals plummeted when ocean-going vessels could travel between the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean via the St. Lawrence Seaway starting in the late 1950s.

Two hundred years after the Erie Canal officially opened on October 26, 1825, it still handles a small amount of commercial shipping, but recreational boaters are its primary users. People also travel the canal by human-powered craft, such as kayaks and canoes, and go by bicycle or on foot on the Erie Canalway Trail that closely parallels the entire length of the waterway. Since 2000, the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor, a partnership of many municipalities, agencies, and organizations, has worked to preserve the historical and natural features of the canal and ensure access to the public.

References & Resources

- The Erie Canal “Clinton’s Big Ditch.” Accessed September 25, 2025.

- Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor (2025) Commemorating 200 Years of the Erie Canal. Accessed September 25, 2025.

- History (2025, May 27) How the Erie Canal Was Built With Raw Labor and Amateur Engineering. Accessed September 25, 2025.

- History of Buffalo (2002, October) The Erie Canal: From Lockport to Buffalo. Accessed September 25, 2025.

- Unlocking New York The Mother of Cities. Accessed September 25, 2025.

- The Washington Post (2025, May 26) The Erie Canal is turning 200. New York is throwing a summer-long party. Accessed September 25, 2025.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Michala Garrison, using shoreline mapping data from the National Geodetic Survey and MODIS data from Blue Marble: Next Generation . Photo courtesy of Town of Clifton Park History Collection, Clifton Park-Halfmoon Public Library Local History Room, via the New York Heritage digital collections. Story by Lindsey Doermann .