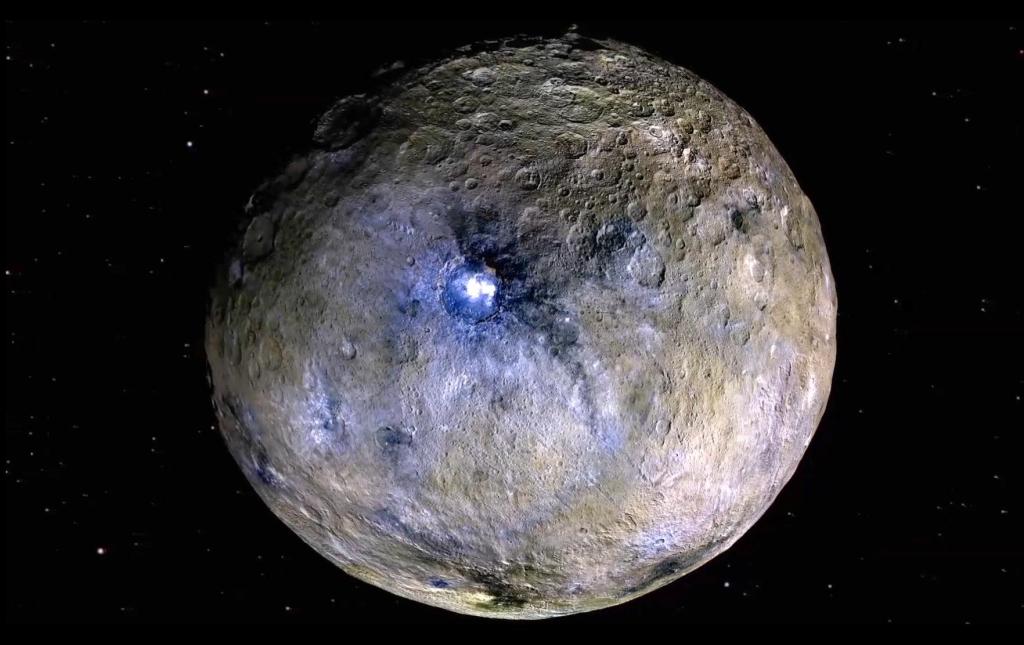

Enceladus Keeps the Home Fires Burning

On Nov. 9, 2006, Cassini's composite infrared spectrometer captured its first view of the infrared heat radiation emanating from the "tiger stripe" fractures at the south pole of Saturn's moon Enceladus (right) since the discovery of the hot spot 16 months earlier (left).

The original discovery was made just before a close flyby of Enceladus on July 14, 2005, and coincided with the discovery of plumes of water-rich gas and ice particles jetting out of the tiger stripes. However, the spacecraft's orbit did not provide any good views of the south pole for follow-up observations until November 2006. The new observations were made from a range of 110,000 kilometers (68,350 miles), slightly more distant than the 80,000-kilometer range (49,700 miles) of the original observations.

Comparison of the two images shows that the south polar region continues to be active, and the distribution of temperatures there has changed little in 16 months. The distribution of heat radiation suggests that most or all of the south polar heat comes from the tiger stripes themselves, though the individual stripes are not resolved at the approximate 30-kilometer (19-mile) spatial resolution of these images.

The images show the intensity of heat radiation in the 10- to 16-micron wavelength range, translated into temperature and displayed in false color. Peak south polar temperature on both dates reached about 85 Kelvin (minus 306 degrees Fahrenheit), averaged over the 30-kilometer (19-mile) spatial resolution of the data. However, the variation in brightness with wavelength, which is also measured by the composite infrared spectrometer, reveals that the warm region includes small areas, possibly zones a few 100 meters (320 feet) wide along the length of the tiger stripes, that are at higher temperatures, reaching at least 130 Kelvin (minus 225 degrees Fahrenheit) and perhaps much warmer still. While the south polar tiger stripes are almost certainly heated by energy from the moon's interior, daytime regions at low latitudes are warmed by sunlight to temperatures in the high 70s Kelvin (about minus 320 degrees Fahrenheit).

The white numbers on the images show west longitudes on Enceladus, which is 500 kilometers (310 miles) in diameter. The dashed line shows the terminator, the boundary between day and night. The blotchy appearance of the cooler regions away from the south pole, and of the sky beyond the globe of Enceladus, is an artifact resulting from the fact that apart from the polar hot spot, the composite infrared spectrometer can barely detect the very faint heat radiation from this very cold moon.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C. The Cassini orbiter was designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The composite infrared spectrometer team is based at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/. The composite infrared spectrometer team homepage is http://cirs.gsfc.nasa.gov/.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL/GSFC/Southwest Research Institute

-Carolyn_Y._Ng.jpeg?w=1024)