Written by Alex Innanen, Atmospheric Scientist at York University

Earth planning date: Friday, June 13, 2025

We’re bidding a fond farewell to “Altadena” this weekend — not only to our drill site, but also to the quad itself. That’s right, we’re back on the road with a drive over almost 48 meters (about 157 feet). But before driving away we have one last sol to wrap up the drill campaign and get one last look at anything in the current workspace. This includes two contact science targets, “Angels Flight” and “Ballona Creek,” and LIBS on a bedrock vein called “Silver Lake.” We’ll also be getting a long distance mosaic on “Boulder Bay,” a boulder on the Texoli Butte. We’re also keeping our usual eye on the environment with a scattering of observations of dust and clouds.

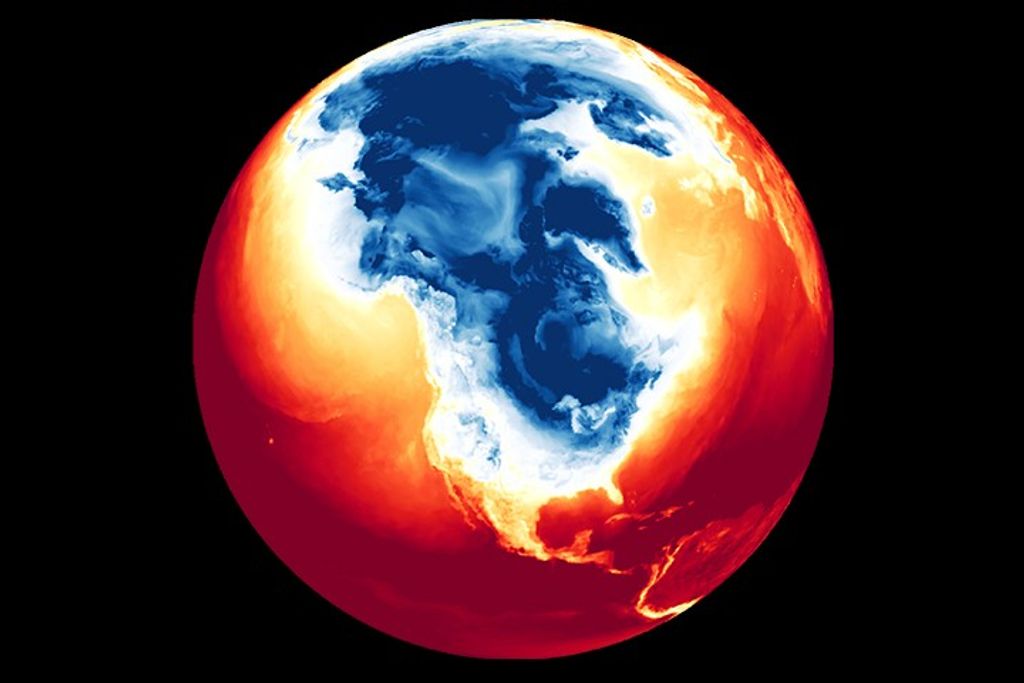

But that’s not the main attraction for the Environmental Theme Group (ENV). We just passed the winter solstice in the Martian southern hemisphere, and there’s been lots of discussion on the blog about how cold it is. While the cold makes power difficult, it does also give us the opportunity to capture something very elusive — frost. The combination of increased humidity (which also gives rise to the cloudy season, which we’re in the middle of) and the deep cold means that conditions are just right for frost to form before sunrise — maybe. We’re going to use ChemCam to search for frost in the pre-dawn hours during this weekend’s plan. Frost is still pretty tricky to make on the Martian surface here at Gale Crater due to a variety of factors.

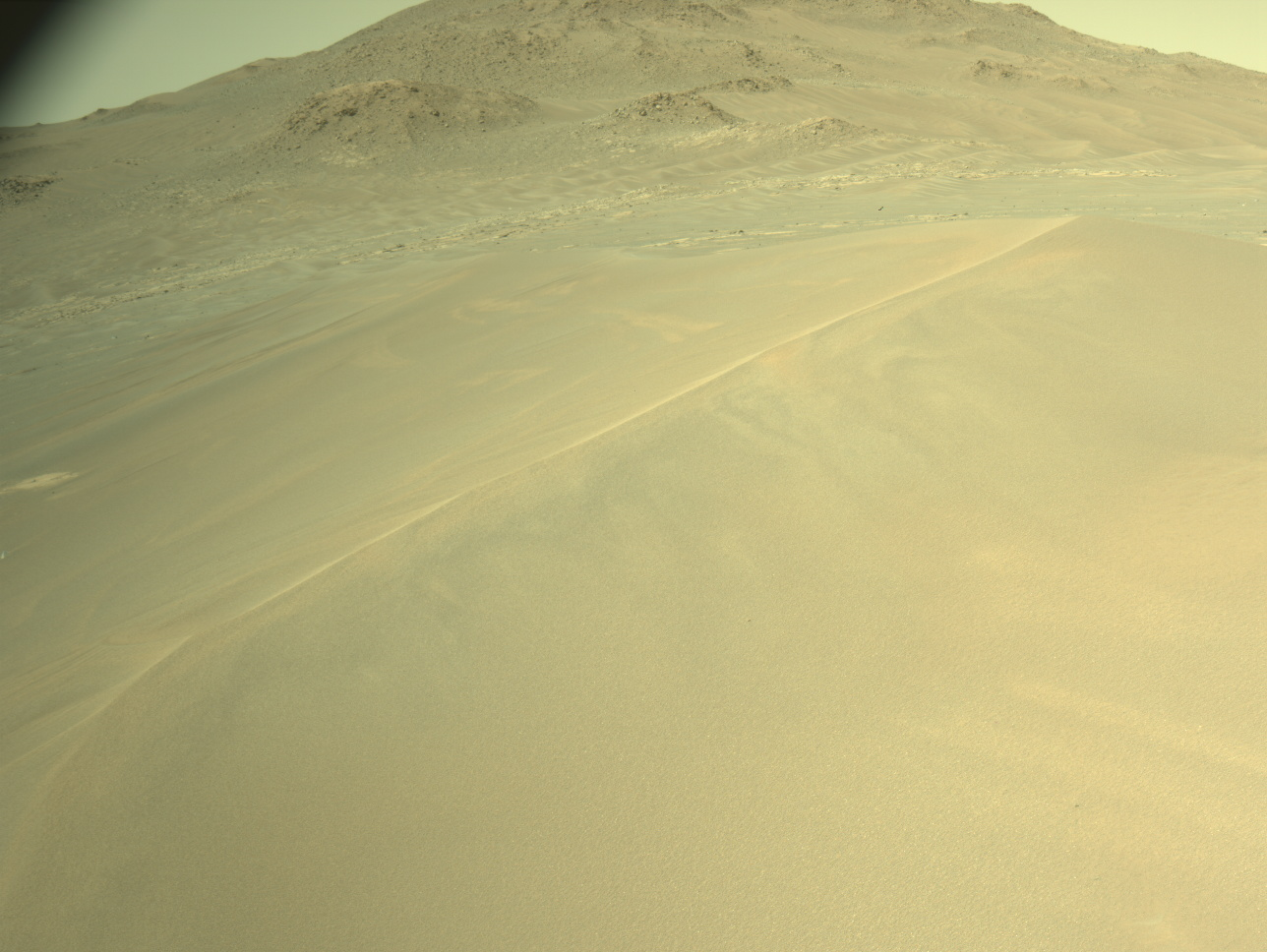

One of these factors is what’s called the “thermal inertia” of the ground, or how quickly a material responds to temperature changes. Think of when you sit on a big, flat rock that’s holding onto the heat of the day even after the Sun has gone down — that rock has a higher thermal inertia. For forming frost, we want low thermal inertia, so that the surface will be as cool as possible and we have the best chance of frost forming. This usually means sand — like how in the winter you may see frost on soil in a garden but not on the sidewalk next to it.

As a longtime ENV-er, I have never had to care much about the ground — usually I’m looking up at the sky, or at least into the far distance, and I don’t need to do things like pick targets. But that’s what I had to do for this weekend’s frost detection. Luckily I was on a line full of people who know a lot about picking targets, and we were able to find a patch of sand that was close enough that ChemCam can use LIBS to tell us if we see frost forming. This little patch of sand was dubbed “Signal Hill,” named after the town in Los Angeles County, but also sharing its name with a famous landmark in Newfoundland in my home country. Hopefully it sends us a signal of the frost we’re looking for!