Earth planning date: Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2024

The star of today’s plan is SAM’s GCMS, which continues our analysis of the “Kings Canyon” drill sample. As Natalie mentioned, this is a relatively energy-hungry activity, but luckily our last plan left us in a good position to not only complete the GCMS experiment but also fit in some other science around it. Having spent a good deal of time in this location for our drill campaign, we’re getting really familiar with this area in a way we don’t get the opportunity to when we’re driving more often. This means lots of geology targets both near and far — a collection to which we’re adding in today’s plan. Nearby, we have two targets for ChemCam’s laser spectrometer, “Meysan Lake” and “Washburn Lake.” Further afield, ChemCam has long-distance mosaics of “Milestone Peak” and our constant companion for many sols, the Kukenan Butte. Mastcam will also be getting a mosaic of the Wilkerson Butte.

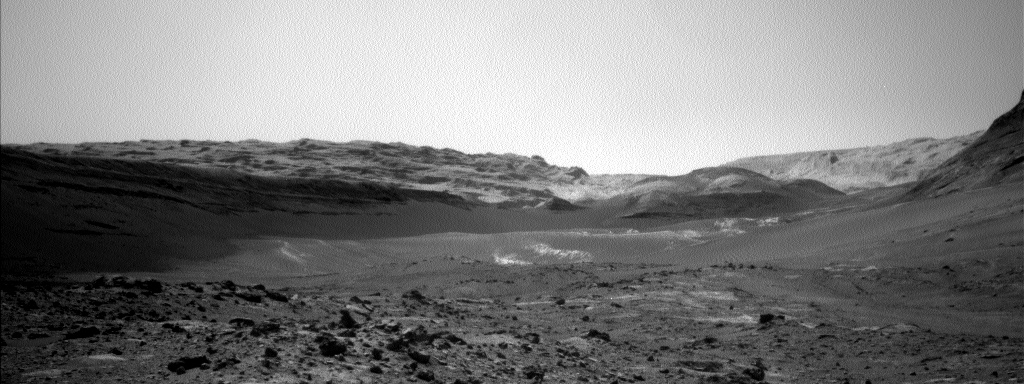

While the atmosphere is always with us, staying in one spot can also grant us good opportunities for keeping an eye on the current environment. We currently have a great view of a nearby sand patch, which you can see in the image above, and we’ve been taking full advantage with lots of dust devil movies, including one in today’s plan. We can also look out for wind-driven movement closer to home, which we’re doing with a Mastcam observation of the drill hole tailings and a Navcam observation of the dust that’s accumulated on the rover deck.

It’s not just near-surface dust we want to keep an eye on, though. The amount of dust suspended in the atmosphere varies throughout the year, and we’re continuing to keep track of that with regular tau observations. The optical depth, which is usually denoted by the Greek letter tau (hence our observation’s name), is a measure of how opaque or transparent the atmosphere is. At this time of year, in the midst of the dusty season, there tends to be more dust suspended in the atmosphere, meaning we cannot see quite as far, and we say the optical depth, or tau, is higher.

Written by Alex Innanen, Atmospheric Scientist at York University