July 23, 1984

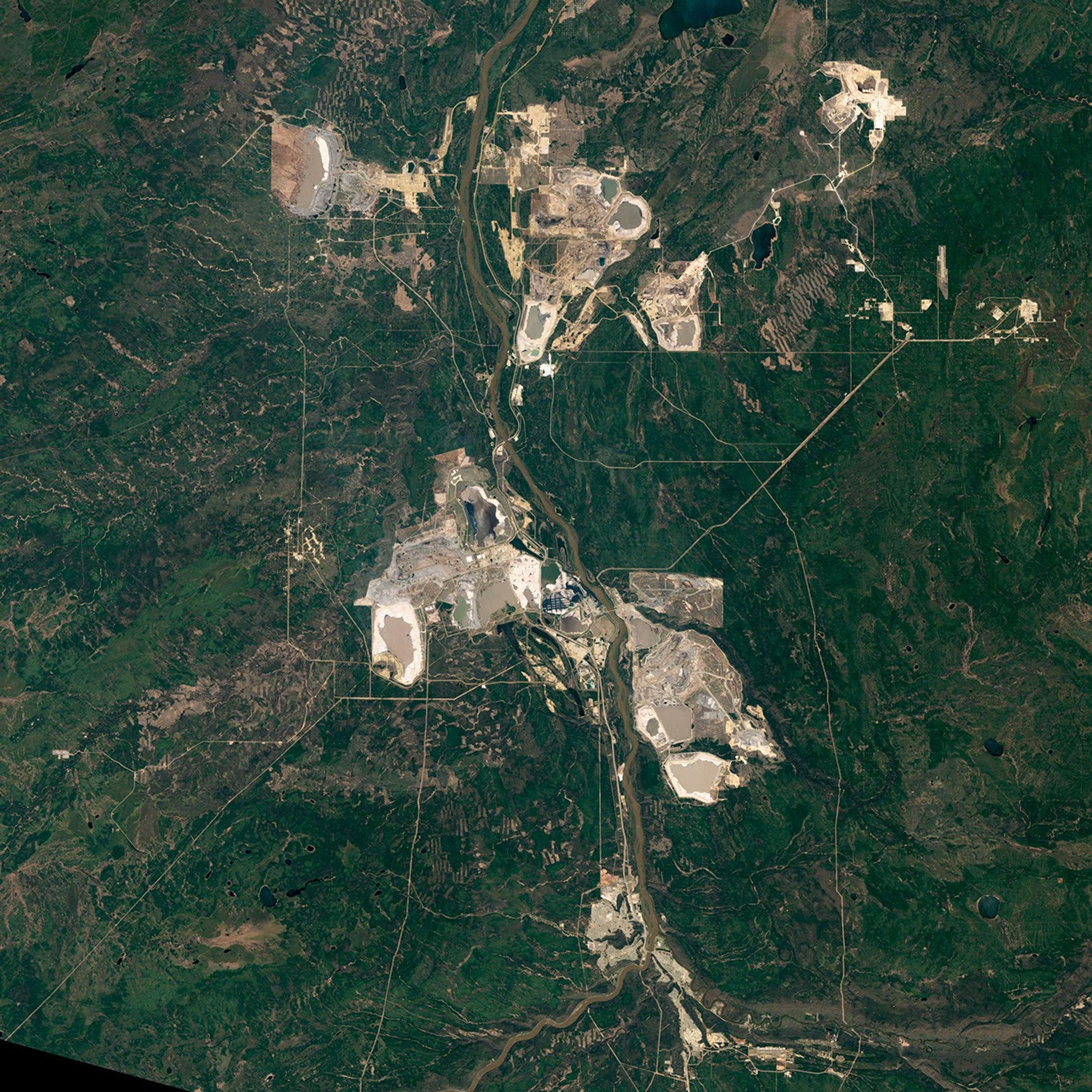

Athabasca Oil Sands

With the rising cost of oil, mining oil sands has become a profitable endeavor in the past decade. Oil sands consist of clay, sand, and other minerals, coated in water and thick, viscous oil called bitumen (or asphalt). To get usable oil from this mixture, producers have to separate the bitumen from the sand using hot water, and then process the bitumen into crude oil. It is an energy-intensive process that until recently cost too much to be profitable. Higher oil prices now offset the cost, and the oil sand industry is growing.

Perhaps nowhere is growth easier to see than at the Athabasca Oil Sands in Alberta, Canada. It is the world’s largest oil sands deposit, with a capacity to produce 174.5 billion barrels of oil—2.5 million barrels of oil per day for 186 years. Where oil sands are close to the surface, they are extracted in large open pit mines. Taken by the Landsat satellites, these natural-color images show the expansion of the mines between 1984 and 2011. Year-by-year images are available in the Earth Observatory’s World of Change series.

Oil sand mining began in Alberta in 1967. That first mine is closest to the Athabasca River in the top image (1984). The mining operation includes a tan pit mine, processing equipment, and tailings ponds, where water and minerals are stored after the oil is removed.

By 2011, pit mines surrounded the Athabasca River. The Mildred Lake Mine, west of the river, began operation in 1996. The Millennium and Steepbank Mines also developed on the east side of the river in the following decade. Additional mines are visible to the north in the large image. In 2010, surface mines produced 356.99 million barrels of crude oil.

Oil sands that are buried more than 80 meters below the land surface are retrieved through in situ wells. Hot water is pumped into the ground to liquefy the oil so that it can be pumped out. Athabasca’s in situ wells yielded 189.41 million barrels of oil in 2010. A grid of white dots defines an in situ operation, MacKay River, west of the Mildred Lake Mine and near the left edge of the image.

Both types of mining operations have a large impact on the environment. As the images show, forest must be cleared for both in situ and surface mining. The mining and extraction process releases sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, hydrocarbons, and fine particulate matter into the atmosphere. Tailings ponds contain a number of toxins that can leak into the groundwater or the Athabasca River. The entire process, from mining and separating oil sands to producing crude oil, releases more greenhouse gases than other oil production methods.

On the other hand, Canada is a country with strict environmental laws that require companies to restore land after mining is complete. A restored tailings pond—the first such restoration project—is visible west of the river. The Athabasca Oil Sands are a stable source of oil for North America, including the United States, the world’s largest consumer of oil.

References & Resources

- Alberta Geological Survey. (2011, April 7). Alberta oil sands. Accessed November 11, 2011.

- Government of Alberta. (2011, November 10). Oil sands projects. Accessed November 11, 2011.

- U.S Energy Information Administration. (2011, November). 2009 world oil consumption. Accessed November 22, 2011.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2011, November 9). World crude oil prices. Accessed November 11, 2011.

NASA Earth Observatory image created by Robert Simmon using Landsat data provided by the United States Geological Survey. Caption by Holli Riebeek.