The Serbian astrophysicist Milutin Milankovitch is best known for developing one of the most significant theories relating Earth motions and long-term climate change. Born in 1879 in the rural village of Dalj (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, today located in Croatia), Milankovitch attended the Vienna Institute of Technology and graduated in 1904 with a doctorate in technical sciences. After a brief stint as the chief engineer for a construction company, he accepted a faculty position in applied mathematics at the University of Belgrade in 1909—a position he held for the remainder of his life.

Milankovitch dedicated his career to developing a mathematical theory of climate based on the seasonal and latitudinal variations of solar radiation received by the Earth. Now known as the Milankovitch Theory, it states that as the Earth travels through space around the sun, cyclical variations in three elements of Earth-sun geometry combine to produce variations in the amount of solar energy that reaches Earth:

- Variations in the Earth's orbital eccentricity—the shape of the orbit around the sun.

- Changes in obliquity—changes in the angle that Earth's axis makes with the plane of Earth's orbit.

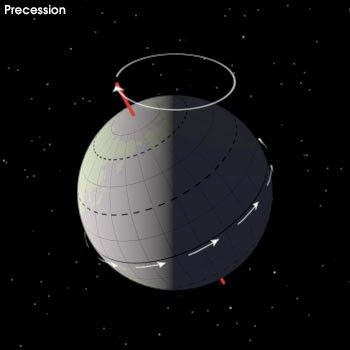

- Precession—the change in the direction of the Earth's axis of rotation, i.e., the axis of rotation behaves like the spin axis of a top that is winding down; hence it traces a circle on the celestial sphere over a period of time.

Together, the periods of these orbital motions have become known as Milankovitch cycles.

Orbital Variations

Changes in orbital eccentricity affect the Earth-sun distance. Currently, a difference of only 3 percent (5 million kilometers) exists between closest approach (perihelion), which occurs on or about January 3, and furthest departure (aphelion), which occurs on or about July 4. This difference in distance amounts to about a 6 percent increase in incoming solar radiation (insolation) from July to January. The shape of the Earth’s orbit changes from being elliptical (high eccentricity) to being nearly circular (low eccentricity) in a cycle that takes between 90,000 and 100,000 years. When the orbit is highly elliptical, the amount of insolation received at perihelion would be on the order of 20 to 30 percent greater than at aphelion, resulting in a substantially different climate from what we experience today.

Note: The eccentricity of the orbit shown in the lower image is a highly exaggerated 0.5. Even the maximum eccentricity of the Earth's orbit—0.07—it would be impossible to show at the resolution of a web page. Even so, at the current eccentricity of .017, the Earth is 5 million kilometers closer to Sun at perihelion than at aphelion. (Images by Robert Simmon, NASA GSFC)

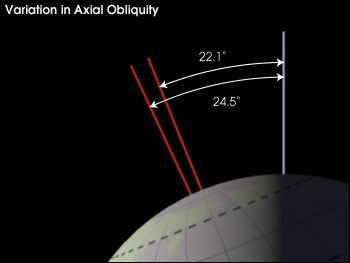

Obliquity (change in axial tilt)

As the axial tilt increases, the seasonal contrast increases so that winters are colder and summers are warmer in both hemispheres. Today, the Earth's axis is tilted 23.5 degrees from the plane of its orbit around the sun. But this tilt changes. During a cycle that averages about 40,000 years, the tilt of the axis varies between 22.1 and 24.5 degrees. Because this tilt changes, the seasons as we know them can become exaggerated. More tilt means more severe seasons—warmer summers and colder winters; less tilt means less severe seasons—cooler summers and milder winters. It's the cool summers that are thought to allow snow and ice to last from year-to-year in high latitudes, eventually building up into massive ice sheets. There are positive feedbacks in the climate system as well, because an Earth covered with more snow reflects more of the sun's energy into space, causing additional cooling.

Precession

Changes in axial precession alter the dates of perihelion and aphelion, and therefore increase the seasonal contrast in one hemisphere and decrease the seasonal contrast in the other hemisphere.

Milankovitch Theory

Using these three orbital variations, Milankovitch was able to formulate a comprehensive mathematical model that calculated latitudinal differences in insolation and the corresponding surface temperature for 600,000 years prior to the year 1800. He then attempted to correlate these changes with the growth and retreat of the Ice Ages. To do this, Milankovitch assumed that radiation changes in some latitudes and seasons are more important to ice sheet growth and decay than those in others. Then, at the suggestion of German Climatologist Vladimir Koppen, he chose summer insolation at 65 degrees North as the most important latitude and season to model, reasoning that great ice sheets grew near this latitude and that cooler summers might reduce summer snowmelt, leading to a positive annual snow budget and ice sheet growth.

But, for about 50 years, Milankovitch's theory was largely ignored. Then, in 1976, a study published in the journal Science examined deep-sea sediment cores and found that Milankovitch's theory did in fact correspond to periods of climate change (Hays et al. 1976). Specifically, the authors were able to extract the record of temperature change going back 450,000 years and found that major variations in climate were closely associated with changes in the geometry (eccentricity, obliquity, and precession) of Earth's orbit. Indeed, ice ages had occurred when the Earth was going through different stages of orbital variation.

Since this study, the National Research Council of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences has embraced the Milankovitch Cycle model.

...orbital variations remain the most thoroughly examined mechanism of climatic change on time scales of tens of thousands of years and are by far the clearest case of a direct effect of changing insolation on the lower atmosphere of Earth (National Research Council, 1982).

Links and References

- Alaska Science Forum: The Earth's Changing Orbit

- J.D Hays, John Imbrie, and N.J. Shackleton, "Variations in the Earth's Orbit: Pacemaker of the Ice Ages," Science, 194, no. 4270 (1976), 1121-1132.

- Hays, James D., 1996: Encyclopedia of Weather and Climate, Oxford University Press, Stephen H. Schneider, ed. pp 507-508.

- Lutgens, Frederick K. and Edward J. Tarbuck, 1998: The Atmosphere, Prentice-Hall, Inc., 434pp.

- National Research Council, Solar Variability, Weather, and Climate, Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1982, p. 7.

NASA Earth Observatory story by Steve Graham