NASA researchers using 22 years of satellite-derived data have confirmeda theory that the strength of “long waves,” bands of atmospheric energythat circle the Earth, regulate the temperatures in the upper atmosphereof the Arctic, and play a role in controlling ozone losses in thestratosphere. These findings will also help scientists predictstratospheric ozone loss in the future.

These long waves affect the atmospheric circulation in the Arctic bystrengthening it and warming temperatures, or weakening it and coolingtemperatures. Colder temperatures cause polar clouds to form, which leadto chemical reactions that affect the chemical form of chlorine in thestratosphere. In certain chemical forms, chlorine can deplete the ozonelayer.

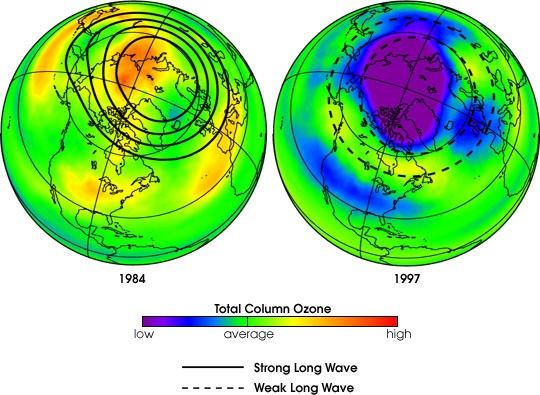

Just as the weather at the Earth’s surface varies a lot from one year tothe next, so can the weather in the stratosphere. For instance, there were some years, like 1984, in which it didn’t get cold enough in theArctic stratosphere for significant ozone loss to occur. “During thatyear, we saw stronger and more frequent waves around the world thatacted as the fuel to a heat engine in the Arctic, and kept the polarstratosphere from becoming cold enough for great ozone losses,” saidPaul Newman, lead author of the study and an atmospheric scientist atNASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, in Greenbelt, Md.

“Other years, like 1997, weaker and less frequent waves reduced theeffectiveness of the Arctic heat engine and cooled the stratosphere,making conditions just right for ozone destruction,” Newman said. Histeam’s research appears in the September 16 issue of Journal of GeophysicalResearch-Atmospheres.

A long wave or planetary wave is like a band of energy, thousands ofmiles in length that flows eastward in the middle latitudes of the upperatmosphere, and circles the world. It resembles a series of ocean waveswith ridges (the high points) and troughs (the low points). Typically,at any given time, there are between one and three of these waveslooping around the Earth.

These long waves move up from the lower atmosphere (troposphere) intothe stratosphere, where they dissipate. When these waves break up in theupper atmosphere they produce a warming of the polar region. So, whenmore waves are present to break apart, the stratosphere becomes warmer.When fewer waves rise up and dissipate, the stratosphere cools, and more ozone loss occurs.

Weaker long waves over the course of the Northern Hemisphere’s wintergenerate colder Arctic upper air temperatures during spring. By knowingthe cause of colder temperatures, scientists can better predict whatwill happen to the ozone layer.

The images above show the relationship between atmospheric long waves in February of1984 (left) and 1997 (right), and ozone. Color represents total ozone anomaly for the month ofMarch—the difference between the measured ozone and the March ozone levelsaveraged over many years. In 1984, strong long waves warmed the Arcticstratosphere, reducing the amount of ozone loss. In 1997, however, weak longwaves were not powerful enough to mix warm tropospheric air into thestratosphere, resulting in greater than normal ozone loss.

References & Resources

Images courtesy Eric Nash and Paul Newman, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

None