Sixty-six million years ago, an asteroid or comet about 10 miles (14 kilometers) wide smashed into Earth. It struck what is now Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, which was then lying at the bottom of a shallow sea. The impact was catastrophic. It triggered tsunamis, started wildfires, and ejected a cloud of ash and dust that circled the globe, blocked the Sun, and chilled the climate. The collision and its aftermath ultimately killed off 75 percent of all life on Earth, including the dinosaurs.

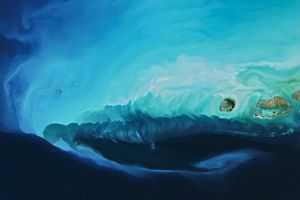

The story was pieced together from evidence littered around the globe, which pointed to a 180-kilometer-wide crater near the coastal town of Chicxulub, on the northern coast of the Yucatán Peninsula. The town of Mérida, which lies inland to south of Chicxulub, appears as a grey-brown area near the top of the image, which was acquired by the

Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer

(MODIS) on NASA’s

satellite on October 31, 2021.

The Chicxulub crater, which now lies partially on land, is the best-preserved large impact crater on Earth. In the millions of years since the impact, the crater has been buried in thick layers of limestone. However, remnants of the crater are still visible at the surface.

A 250-kilometer-long arc of sinkholes marks the crater rim. These sinkholes, called cenotes, provided freshwater to the ancient Mayan inhabitants of the peninsula. The area otherwise lacks surface water due to the karst (soluble limestone) landscape. Because rainwater is slightly acidic, surface water dissolves and seeps down through the limestone bedrock, creating solution pits, cenotes, and caves, as well as the world’s longest underground river.

When those thick layers of limestone erode, the chalky sediments wash out onto the broad, shallow Yucatán Shelf. In this natural-color image, the swirls of sediment are visible off the north and west coast in the Bay of Campeche.

Sediment scatters light, and this reflectivity gives water characteristic color when viewed from space. When floating near the surface, sediment appears muddy-tan, but as it sinks and disperses the color changes to shades of green and light blue. When the shallow coastal waters are churned by winds, tides, storms, or currents, seafloor sediments can be resuspended, causing the seawater to look white or pale blue. Some of the color may also come from phytoplankton—microscopic plant-like organisms—that sometimes float on the surface in blooms large enough to be seen from space.

References & Resources

- Alvarez, W. (1997) T. Rex and the Crater of Doom. Princeton University Press.

- Lunar and Planetary Institute (2019) Chicxulub Discovery Website. Accessed November 19, 2021.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2015, January 4) Progressoâs Prolonged Pier.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2003, March 7) Relief Map, Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico.

- Reuters (2007, March 1) Longest Underground River Found. Accessed November 19, 2021.

- Winemiller, T. (2014) GIS Reveals Basis for Ancient Settlement Location. Accessed November 19, 2021.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview . Story by Sara E. Pratt.