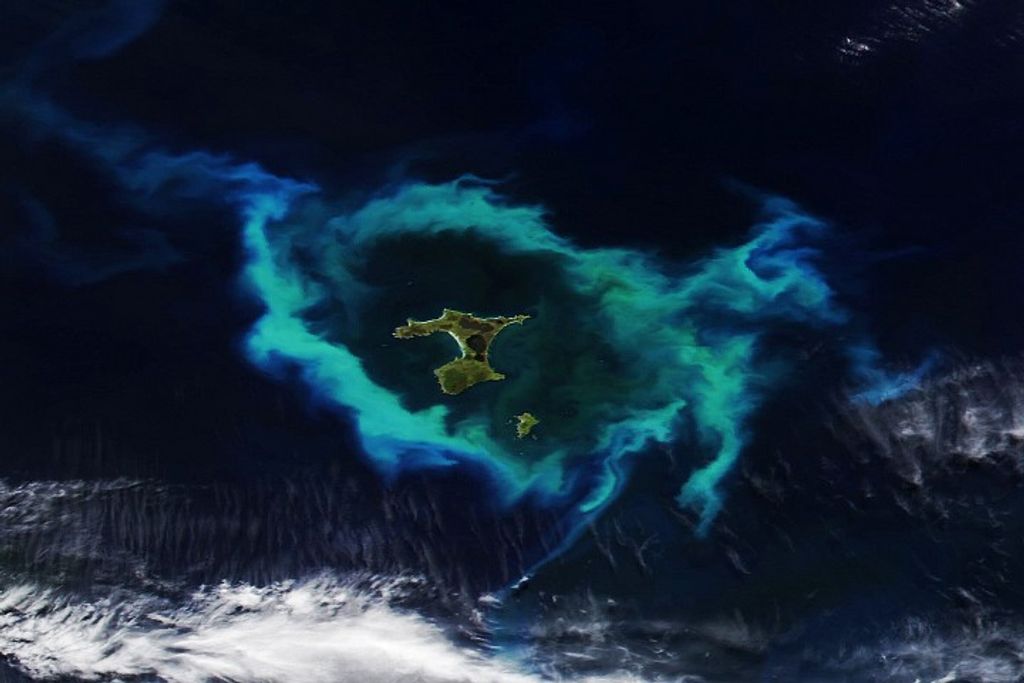

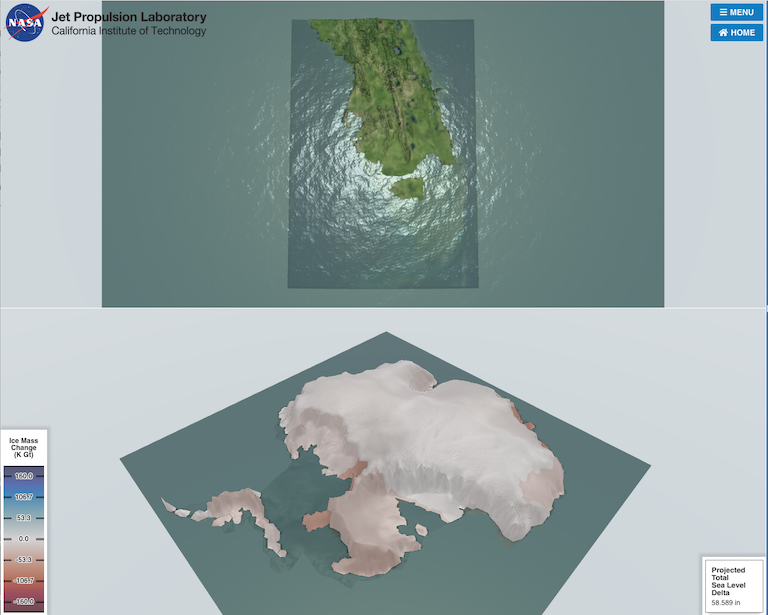

Warm the Antarctic, and southern Florida drowns. And as West Antarctica melts, its famous peninsula becomes an island.

These calamities are, for now, safely contained in a web-based simulation just released to the public. You can take charge of the controls – ice melt caused by a warming ocean, snowfall, temperature, friction – and get a feel for how a warming world could diminish the frozen continent and raise sea levels over the coming century.

But the newest simulation from scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory isn’t just an entertaining toy. It’s fed by real data from the powerful Ice Sheet System Model, or ISSM – the same computer model scientists use to try to predict how quickly polar ice will melt, as well as where, and when, rising seas will inundate shorelines.

The sliding control features of the simulation – more or less ice melt, higher or lower snowfall – track some of the same changes researchers must grapple with as they try to project real-world effects into the future.

It’s meant, in part, to give all of us a more detailed picture not only of the possible changes to come, but of just where the uncertainties lie.

“There are pretty large uncertainties in specific, key parameters needed to even run an ice sheet model,” said JPL Earth scientist Nicole-Jeanne Schlegel, lead author of a recent paper that tries to better define these areas of uncertainty.

At the same time, the paper attempts to show both the worst-case scenarios and less extreme but more likely outcomes – which still would have profound effects on Antarctica and distant shorelines.

Both Arctic and Antarctic ice is melting in response to warming temperatures, amounting to net losses in the hundreds of gigatons per year. Along with warming, expanding ocean water, ice melt is driving sea levels higher, and the rate of rise is accelerating.

But projecting these changes into the future requires a deep understanding of key variables: snowfall, ice melt caused by warming ocean waters, how easily glaciers slide along their bedrock base and the temperature of the ice itself.

Modelers also must provide a range of estimates for factors that cannot be determined precisely. Whether human emissions of climate-warming, greenhouse gases will rise, fall or remain about the same is one of these big unknowns.

Vulnerable Regions

After multiple computer modeling runs under several scenarios – in other words, putting the model through its paces as it simulates Antarctic ice melt and resulting sea-level rise over the next century – one factor loomed large, Schlegel said.

“One of the major results was that ocean forcing (warming ocean water melting ice from below) really dominates over all the others,” she said. “It causes the largest spread of uncertainty.”

Knowing which factors cause the greatest uncertainty will help sharpen modeling projections.

The study also revealed that under the most extreme warming scenario over the next 100 years, the Amundsen Sea sector in the western portion of the continent has the largest potential sea level contribution – 297 millimeters, or nearly a foot of global sea level rise.

But oddly, under a less extreme but more scientifically likely scenario, Antarctica’s Ronne basin, in the northwest, moves into first place. Melting ice streams in this basin could cause about half a foot (161 millimeters) of sea level rise.

And these are only two of the modeled contributions. Combine all the other sources of expected ice melt and ocean expansion, and scientists estimate that we could see several feet of sea level rise in the century ahead.

The new study continues a critical, long-term effort of sea level scientists: narrow uncertainty and improve the accuracy of ice-melt simulations.

“It ends up being a very important future endeavor for us, model-wise,” Schlegel said. “It’s very important to know how ocean temperature progresses as ice changes.”