By Alan Buis,

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

David Hosansky,

National Center for Atmospheric Research

A unique and complex set of circumstances came together over Australia from 2010 to 2011 to cause Earth's smallest continent to be the biggest contributor to the observed drop in global sea level rise during that time, finds a new study co-authored and co-funded by NASA.

In 2011, scientists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., and the University of Colorado at Boulder reported that between early 2010 and summer 2011, global sea level fell sharply, by about a quarter of an inch, or half a centimeter. Using data from the NASA/German Aerospace Center's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) spacecraft, they showed that the drop was caused by the very strong La Niña that began in late 2010. That La Niña changed rainfall patterns all over our planet, moving huge amounts of Earth's water from the ocean to the continents. The phenomenon was short-lived, however.

By mid-2012, global mean sea level had resumed its long-term mean annual rise of 0.13 inches (3.2 millimeters) per year (see http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2012-362).

But analyses of the historical record showed that past La Niña events only rarely accompanied such a pronounced drop in sea level. So what made this particular La Niña unique?

To better understand this phenomenon, scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colo.; JPL; and the University of Colorado at Boulder combined GRACE data with data from the Argo global array of 3,000 free-drifting floats and satellite altimeters (Jason-1, Jason-2 and Topex/Poseidon).

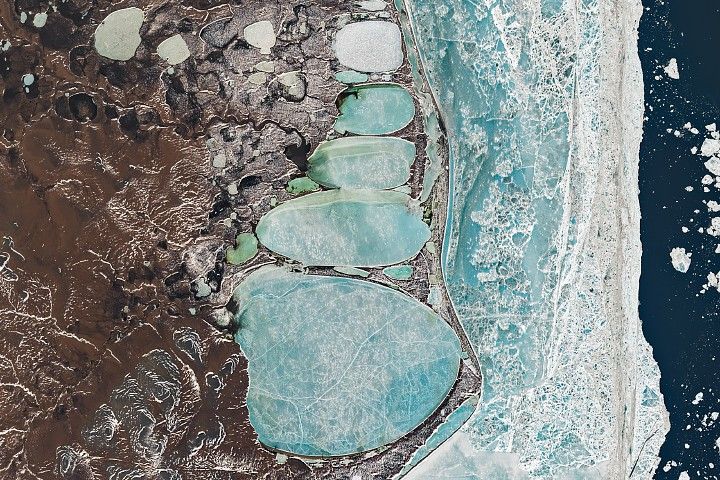

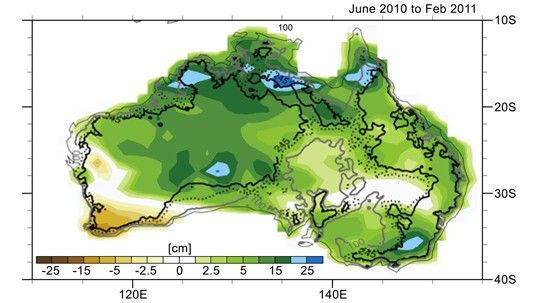

They found that three atmospheric patterns converged over the Indian and Pacific Oceans in 2010 and 2011 to drive excessive precipitation over Australia. On average, the continent received almost one foot (300 millimeters) of rain more than normal. The result was widespread flooding. The flooding was in large part prevented from running back into the ocean by Australia's dry soils and the mountain-ringed topography of the country's vast interior, called the Outback, leading to the measurable drop in the world's ocean levels.

"No other continent has this combination of atmospheric set-up and topography," said NCAR scientist John Fasullo, lead author of the study. "Only in Australia could the atmosphere carry such heavy tropical rains to such a large area, only to have those rains fail to make their way to the ocean."

Now that the atmospheric patterns have snapped back and more rain is falling over tropical oceans, the seas are rising again. In fact, with Australia in a major drought, they are rising faster than before. Since 2011, when the atmospheric patterns shifted out of their unusual combination, sea levels have been rising at a faster pace of about 0.4 inches (10 millimeters) per year.

The study, co-funded by NASA and the National Science Foundation, will be published next month in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

For more information, read the full NCAR news release: http://www2.ucar.edu/atmosnews/news/10090/global-sea-level-rise-dampened-australia-floods.