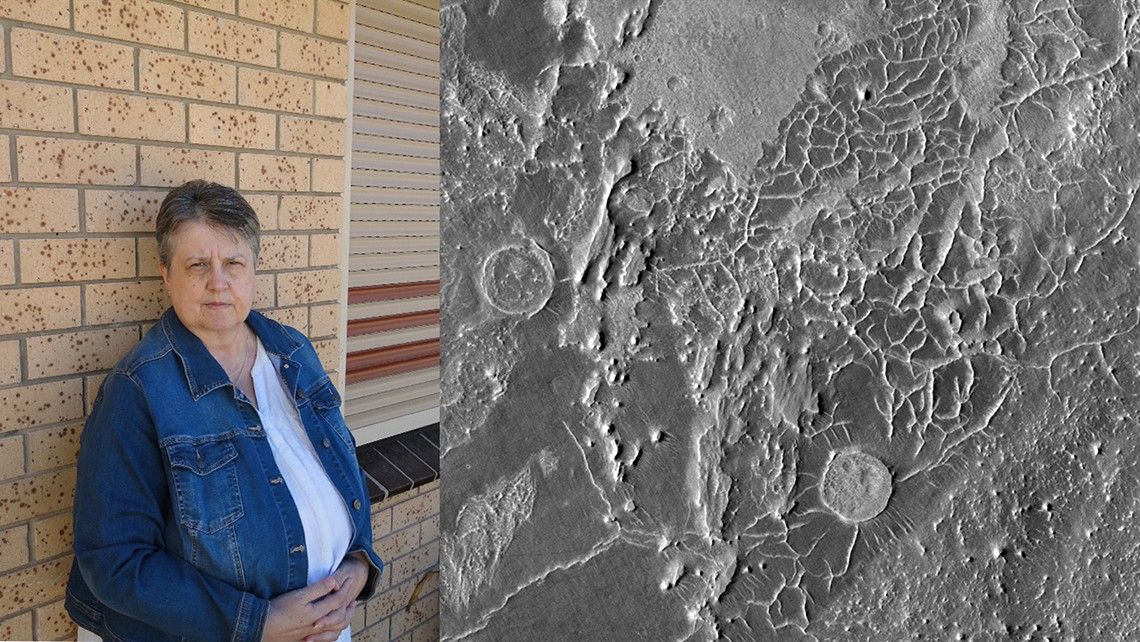

In the mornings, Sylvia Beer sits at the desktop computer in her living room with a cup of coffee and looks for ridges on Mars. Her town of Wodonga, Australia, gets so hot that in summer she begins scanning Mars images at 4 a.m., when she takes medication for Parkinson’s disease. The condition sometimes affects her memory and movement — she uses a cane or walker to get around, and can’t walk as far as she’d like — but her passion for learning about space has not suffered.

“It’s been since I was about 5 years old. It’s been in my blood since then,” said Beer, now 61. “Just the wonderment and trying to understand how everything goes together and works — I just love it.”

More About Citizen Scientists

Beer is one of hundreds of thousands of people worldwide participating in “citizen science” initiatives using NASA data that allow anyone, regardless of education or background, to collaborate in real scientific research. Many enthusiastic amateurs have day jobs as wide ranging as making furniture, teaching and leading cruises in the Arctic and Antarctica. And the projects they collaborate on make valuable discoveries: networks of ridges on Mars, a meteor impact on Jupiter and even previously unknown systems of planets orbiting other stars, known as exoplanets.

Some projects, such as Planet Four, which Beer contributes to, rely on the public to identify patterns and features in the massive amounts of data NASA spacecraft beam home. Others allow citizen scientists to log observations about their environments, collecting Earth science data from around the globe — which would be difficult for a small professional science team.

“Citizen science projects democratize science and open up avenues for people to participate who might not have chosen science as a career, or who are still in school and thinking about going into science,” said Amy Kaminski, program executive for NASA’s Prizes and Challenges program.

Thousands of Eyes on Mars

Spacecraft have returned hundreds of thousands of images of Mars, and scientists — who tend to specialize in specific aspects of Mars — don’t have time to carefully look at every single one, or examine them in the context of the whole planet. That’s why Planet Four, a citizen science project on the Zooniverse platform, launched in 2013.

“There is far more data from our spacecraft out there than there are scientists to make good use of it,” said Doug Ellison of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, who was a citizen scientist before joining JPL. “Because these data are out there, they have sprouted — they have germinated and nurtured — an army of people who will help scientists unlock its potential. All we have to do is release the data and leave them alone.”

In 2017, the Planet Four project teamed with JPL scientist Laura Kerber to launch a project called Planet Four: Ridges to see how common different kind of ridges are on Mars. Participants look through thousands of images from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and click “Yes” or “No” on each one to indicate whether they see a ridge or not. More than 8,000 people have viewed over 40,000 frames from MRO images in “Ridges.” Because different people may interpret ridges differently, the program shows the same image to multiple people and then delivers the ones with the most “yes” votes to the scientists.

“The most valuable thing is them saying, ‘Laura, I found something unusual.' A machine can be like, ‘Okay, I have results.’ The machine can’t tell me what else it learned in its journey.”- Laura Kerber

“By having so many people look at the same image and combine those assessments, it typically outperforms or equals the experts,” said Meg Schwamb, an astronomer at Gemini Observatory in Hawaii, who helped develop Planet Four.

Kerber has been astounded — not only at how well participants spot ridges, but how their curiosity leads them to point out other features of interest. Sylvia Beer, the Australian space enthusiast, looks for ridges on Google Mars, which also makes use of NASA spacecraft images, and reports her findings through Planet Four. Beer has spotted many ridges in the oldest areas of Mars, which indicates to Kerber that water was pervasively flowing through the ancient crust.

“The most valuable thing is them (the citizen scientists) saying, ‘Laura, I found something unusual,’” Kerber said. “A machine can be like, ‘Okay, I have results.’ The machine can’t tell me what else it learned in its journey.”

A Crowd-controlled Camera at Jupiter

One of the active amateurs monitoring Jupiter is Christopher Go, who lives in Cebu City, Philippines. By day he manufactures furniture, but in the early mornings he is observing the sky and processing images from JunoCam, a visible-light camera on NASA’s Juno spacecraft. Go is also known for having confirmed a meteor’s flashy impact into Jupiter in 2010, which he captured on video.

“The planets are very dynamic so every day your image is different,” he said. “You see new things. You make discoveries every day.”

JunoCam is not formally part of the science goals for Juno, which has been orbiting Jupiter since July 2016, and relies on amateurs for many tasks that a professional team would otherwise handle. Candice Hansen, Planet Four co-founder and senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, was put in charge of an interplanetary camera that is, in some sense, directed by the public.

“The vision was to have the public participate — not just passively view things on the web, but give them a chance to participate in every element of what it takes to operate an experiment flying on a spacecraft,” Hansen said.

Because of the camera’s design and the spacecraft’s orbit, JunoCam can’t take a useful, high-resolution image of the entire planet at once. But amateur astronomers who have access to telescopes on Earth can upload their photos of Jupiter to the JunoCam website so that the community knows what Jupiter looks like on any given day. This is important because Jupiter’s belts, clouds and storms are always changing.

Hansen’s team makes a map every two weeks using amateur images, including Go’s, and shares it with the public. Then, people can pick out individual features on Jupiter they find interesting and even name them. In Juno’s first eight orbits around Jupiter, the public could also vote on where JunoCam would focus its gaze — taking the place of closed-door decision-making meetings of scientists that happen on other missions. Juno’s current 53-day orbit means this is no longer feasible, as it’s hard to predict what exactly will come into view during close approach. But images of the whole planet from people like Go are essential for putting the JunoCam images in context.

Each participant has a unique eye for Jupiter — Bjorn Jonsson in Iceland, for example, reconstructs how Jupiter’s colors would look to an astronaut aboard Juno, but also offers enhanced versions that make those colors pop. Artist “Wintje” uses Jupiter as an inspiration for colorful, futuristic re-imaginings. And the images do matter for science: JunoCam imagery processed by the public has led to new insights about Jupiter’s circumpolar cyclones, for example.

“We get everything from very scientifically usable renditions to works of art,” Hansen said.

“I honor that people choose to spend their free time doing this. It really blows me away.”

GLOBE Observers

Back on Earth, the public has been exploring their own planet through a program called Global Learning and Observations to Benefit the Environment, or GLOBE, since the 1990s. Sponsored by NASA and supported by the National Science Foundation, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Department of State, GLOBE originally trained teachers to do citizen science data collection with their students. But in 2016, a smartphone app called Globe Observer launched to broaden the participant pool to anyone in the more than 100 countries participating in GLOBE to submit data.

One of the app’s main projects involves clouds. Clouds help regulate the temperature of our planet, and different kinds of clouds impact weather differently. Scientists also want to know how clouds are evolving with climate change, as Earth’s average temperature warms. Through the app, members of the public take pictures of clouds, observe clouds in the sky and compare their findings with images from NASA satellites.

“Satellites can make some measurements but we want to be able to verify that satellites are giving us accurate information about the clouds,” said Kristen Weaver, deputy coordinator for the app at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

The app had a particularly wide appeal during the Aug. 21, 2017, solar eclipse, which could be viewed at least partially from the entire United States. Scientists were interested in how much the air temperature dropped in different locations as the Moon blocked the Sun, and how much this was related to cloud cover. Enthusiastic eclipse viewers scattered throughout the country were perfect for collecting this information. GLOBE Observer app users — whose numbers more than tripled for this event — submitted over 80,000 air temperature measurements, 20,000 cloud observations and 60,000 cloud photos. Professional researchers are still analyzing this information.

One of the GLOBE Observer eclipse watchers was Ocean McIntyre, who works at JPL. Long before she joined NASA’s Europa Clipper mission as a science assistant, Mcintyre was chasing endangered butterflies as a citizen scientist. “If someone had asked me 25 years ago while I was crawling through the brush looking for those tiny blue butterflies, where I thought it would take me, I never would’ve suspected that it would lead to working on a NASA mission to look for life the ingredients of life on an icy moon of Jupiter,” she said. Read about it in her own words.

GLOBE Observer explorers can also help scientists monitor disease-carrying mosquitoes through the Mosquito Habitat Mapper. Participants report sources of standing water such as ponds and ditches, where mosquitoes might live. With the addition of a smartphone microscope attachment, citizen scientists can examine mosquito larvae — which don’t bite — to see what type of mosquitoes live there. Researchers at Goddard can then combine this information with satellite imagery to look for trends in where mosquitoes may be spreading illness.

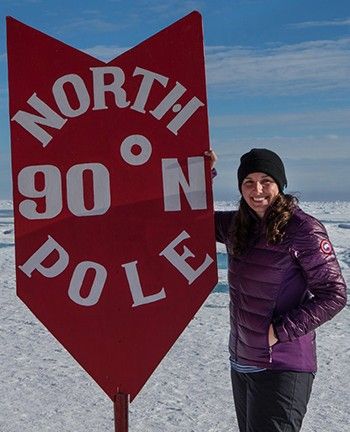

“No matter where we live or what we do, if we work together, we are a powerful army of data collectors,” said Lauren Farmer, a citizen scientist in Canberra, Australia, who participates in GLOBE Observer and is a guide for expedition cruises in Antarctica and the Arctic. “I’m proud to spend my time contributing to citizen science and hopefully inspiring others to do the same.”

Other Earth-observing projects include Aurorasaurus, which led scientists to the unique purple aurora amateur astronomers named “Steve.” A team led by Liz MacDonald at Goddard recently solved the mystery of Steve’s nature thanks to citizen scientist observations.

Five extraordinary discoveries by citizen scientists

Beyond the Solar System

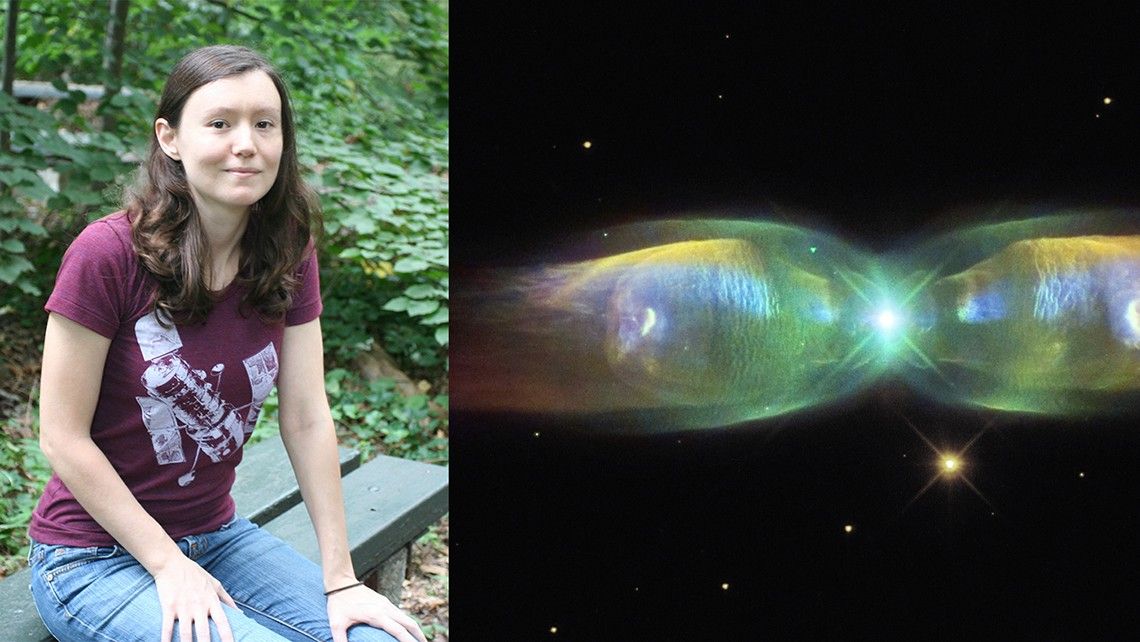

Citizen scientists also play a key role in discoveries far beyond Earth. In 2017, thousands of members of the public flocked to a Zooniverse project called Exoplanet Explorers when it was featured on an Australian TV show — and, as a result of these efforts, scientists found a multiplanet system called K2-138. Researchers announced in January 2018 that the system has five planets, and perhaps even a sixth. This is the first extrasolar system with multiple planets that has been discovered through crowdsourcing. What’s more, the planets are in a resonant chain, with a set numerical relationship between their orbits, indicating the system could not have formed in a chaotic, violent way.

“There is far more data from our spacecraft out there than there are scientists to make good use of it.” - Doug Ellison

“It was just this really amazing system that popped straight out,” said Jessie Christiansen, exoplanet researcher at Caltech/IPAC in Pasadena and co-founder of Exoplanet Explorers. “It teaches us things about planetary formation that we didn’t know before.”

Exoplanet Explorers allows members of the public to look for exoplanets, which are planets outside the solar system. It makes use of data from NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope, which stared at the same patch of sky from 2009 to 2013, and continues in a second mission, known as K2, that views different areas along the plane of Earth’s orbit. Citizen scientists are on the lookout for signs that a planet has passed across the face of its host star – an event called a transit.

Other discoveries have come from more distant space, using NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) spacecraft and other telescopes. Disk Detective, which asks participants to look for debris disks around stars, led scientists to the oldest known circumstellar disk, changing our picture of how long planet-forming disks can survive. Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 has revealed at least 17 confirmed brown dwarfs, objects that span the range from planets almost up to the mass of stars. Both of these projects originated with Marc Kuchner, an astrophysicist at Goddard.

The most ambitious users of these projects receive special access to Google Hangouts with the science team and participate in side projects — sometimes even volunteering to go with scientists to observatories to follow up. These “super users” have translated Disk Detective into 11 different languages and served as co-authors on publications that resulted from the projects. By day, their jobs range from pulmonologist to high school student. Computer technician Hugo Durantini Luca of Cordoba, Argentina, is one published super user — he used a telescope for the very first time when he followed up on Disk Detective targets.

“I knew citizen science would be a way to reach a large group of people, but I didn’t realize how important these people would become in my life,” Kuchner said. “I wish I could get to know all 150,000 of them!”

When Les Hamlet of Springfield, Missouri, got involved with Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 last year, he was working as a restaurant cook and knew little about spreadsheets and data analysis. But after a few months with the citizen science project, Hamlet was so hooked on looking for exotic astronomical objects that he learned how to write scripts and query databases. He has found more than 30 brown dwarf candidates so far, and one has been confirmed. Today, he works as a lab technician for an engineering firm. Through citizen science, “I learned a lot of skills that help me in my job right now,” he said.

Building Community

A feature of the Zooniverse platform that Hamlet, Beer and other citizen scientists enjoy is the ability to talk to one another.

Beer is part of a core group of space enthusiasts using Planet Four: Ridges who regularly discuss their observations and ideas. One member, Bill Hood of Manitoba, Canada, a geologist who does mineral exploration for mining companies, describes the group as a “subculture.” Retired IT specialist Fernando Nogal of Lisbon, Portugal, has a reputation for being “the database guy,” and has been fascinated by the Martian south pole. Besides talking about Mars, there are jokes about cricket and weather reports from each person’s pocket of the globe. “I bring the cold weather and ice perspective to the discussion,” Hood said.

Beer’s highest level of education is high school, and she has had a wide variety of jobs, from working in a bakery to assisting with research in child psychology. She was born in Germany, but also lived in the United States and Central America before settling in an area of Australia home to kangaroos, horses, llamas and alpacas.

“People think I’m from Canada because of my strange accent,” she said. “I say, ‘no, I’m from Earth.’”

When she’s not looking for ridges on Mars, Beer enjoys making art. Drawing is difficult these days because her hands twitch, but she still designs colorful tapestries and jewelry — which also involves her keen sense of pattern recognition. She also loved mountain climbing when she was physically able to do it, and dreamed of seeing the Moon from space.

“If I was healthy, they could have sent me to Mars, to the Moon. I would have gone,” Beer said.

“But I’ve got a page [screen] saver that’s got the Moon and Earth rising. That’s how things are. You never know. I’m just glad I’ve got something to keep me occupied. I think my mind needs that.”