http://uanews.opi.arizona.edu/cgi-bin/WebObjects/UANews.woa/wa/SRStoryDetails?ArticleID=4950

University of Arizona News Services

Aaron Farnsworth, 520-621-1877

Europa, Jupiter's smallest moon, might not only sustain but foster life according to the research of a University of Arizona professor.

Richard Greenberg, a professor of planetary sciences and member of the Imaging Team for NASA's Galileo Jupiter-orbiter spacecraft, reported in the February issue of American Scientist that a combination of several factors could create habitable niches.

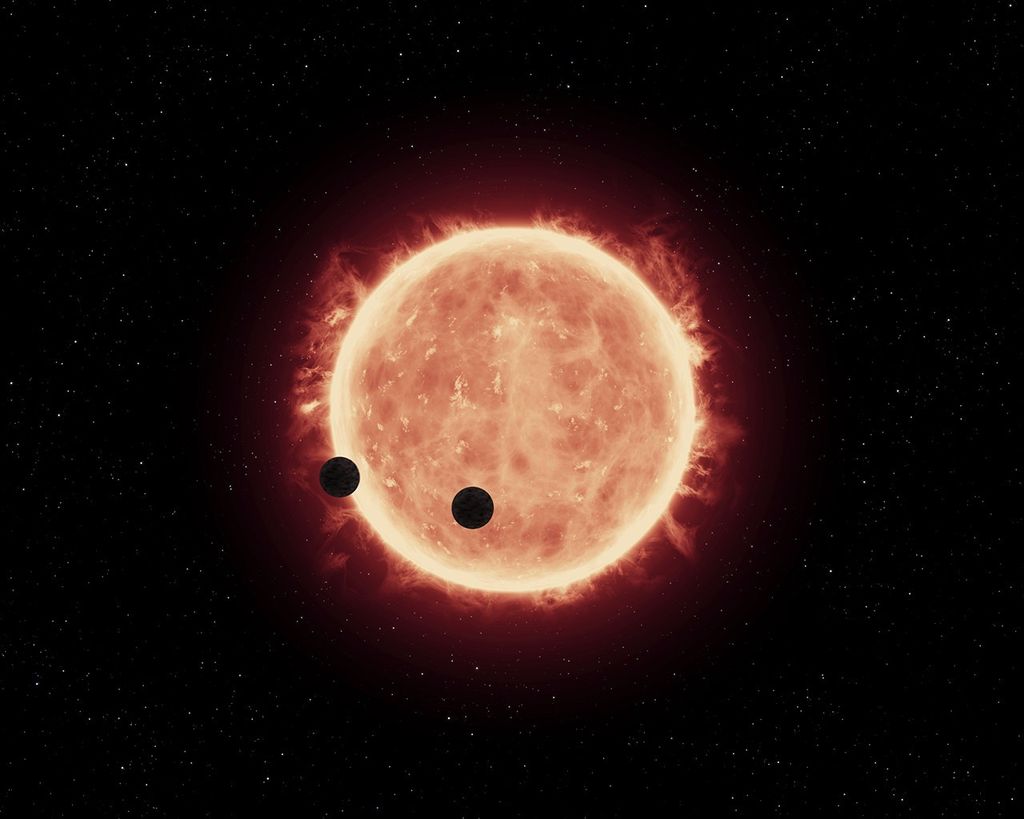

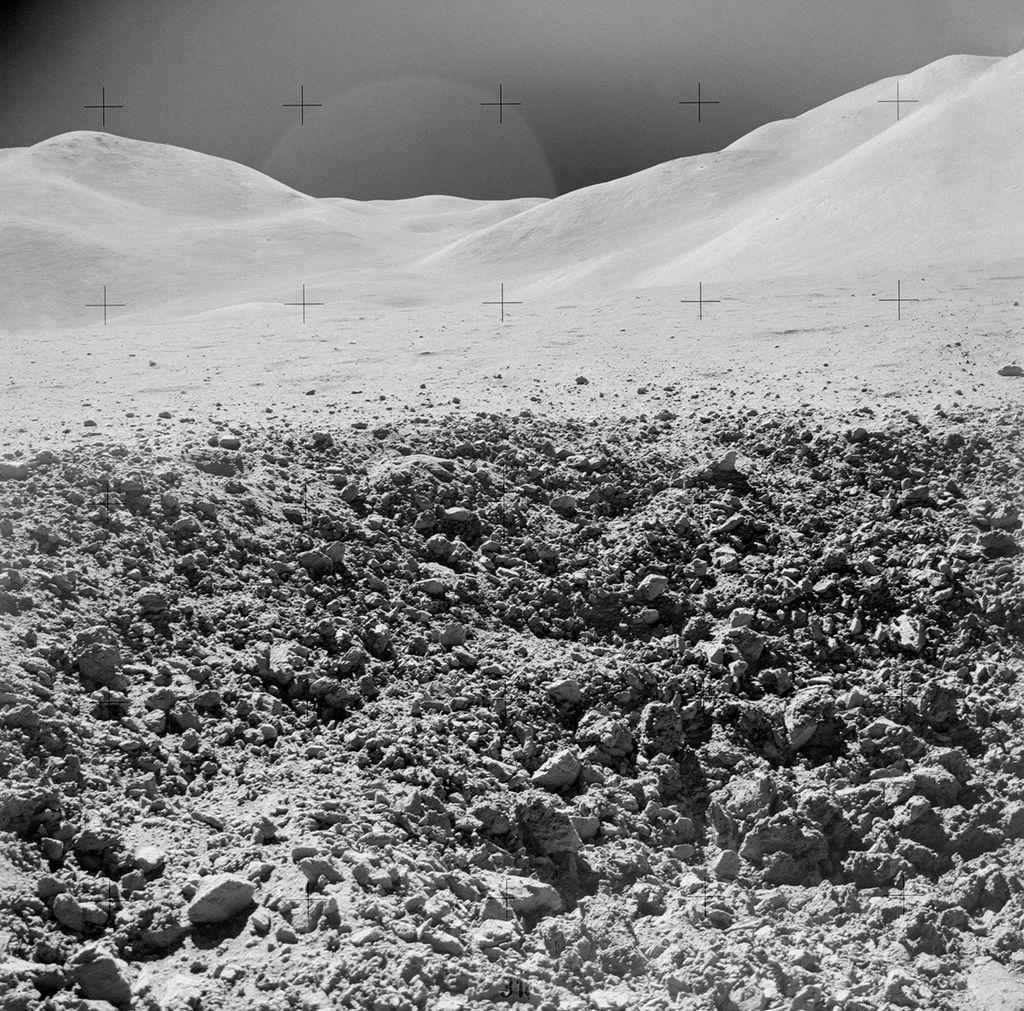

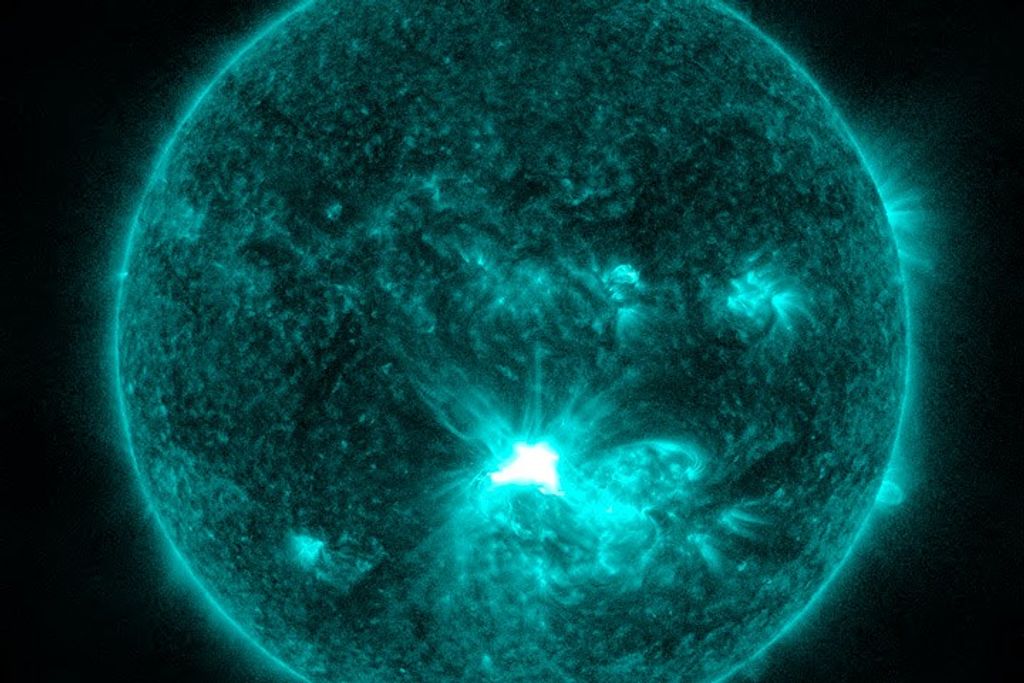

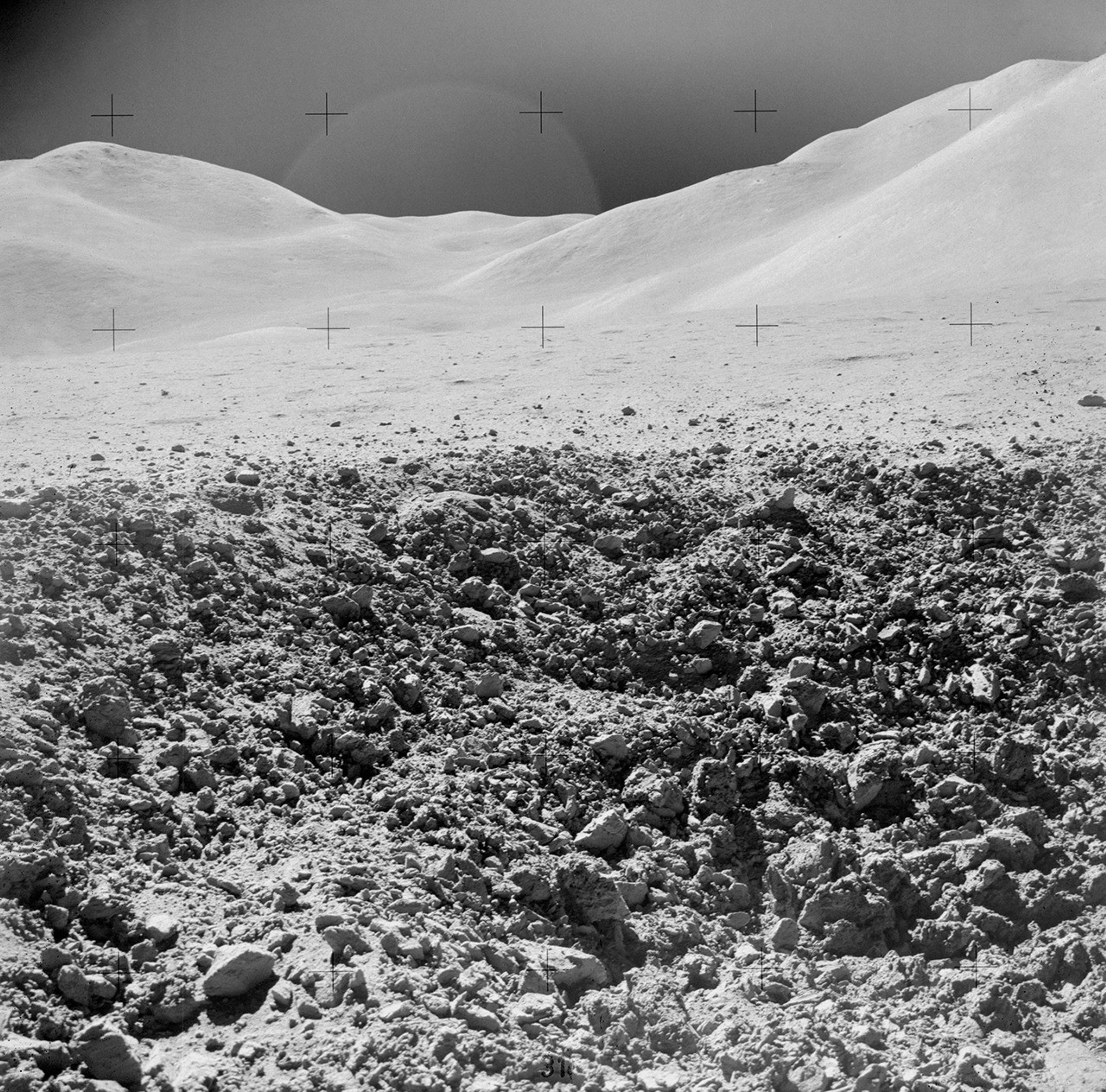

Europa, similar in size to Earth's moon, has been imaged by Galileo for the last 4 years. Its surface, a frozen crust of water, was previously thought to be tens of kilometers thick, denying the oceans below any exposure.

The combination of tidal processes, warm waters and periodic surface exposure may be enough to not only warrant life but also encourage evolution, Greenberg said.

"The implication is that these settings would actually be hospitable to life," he said.

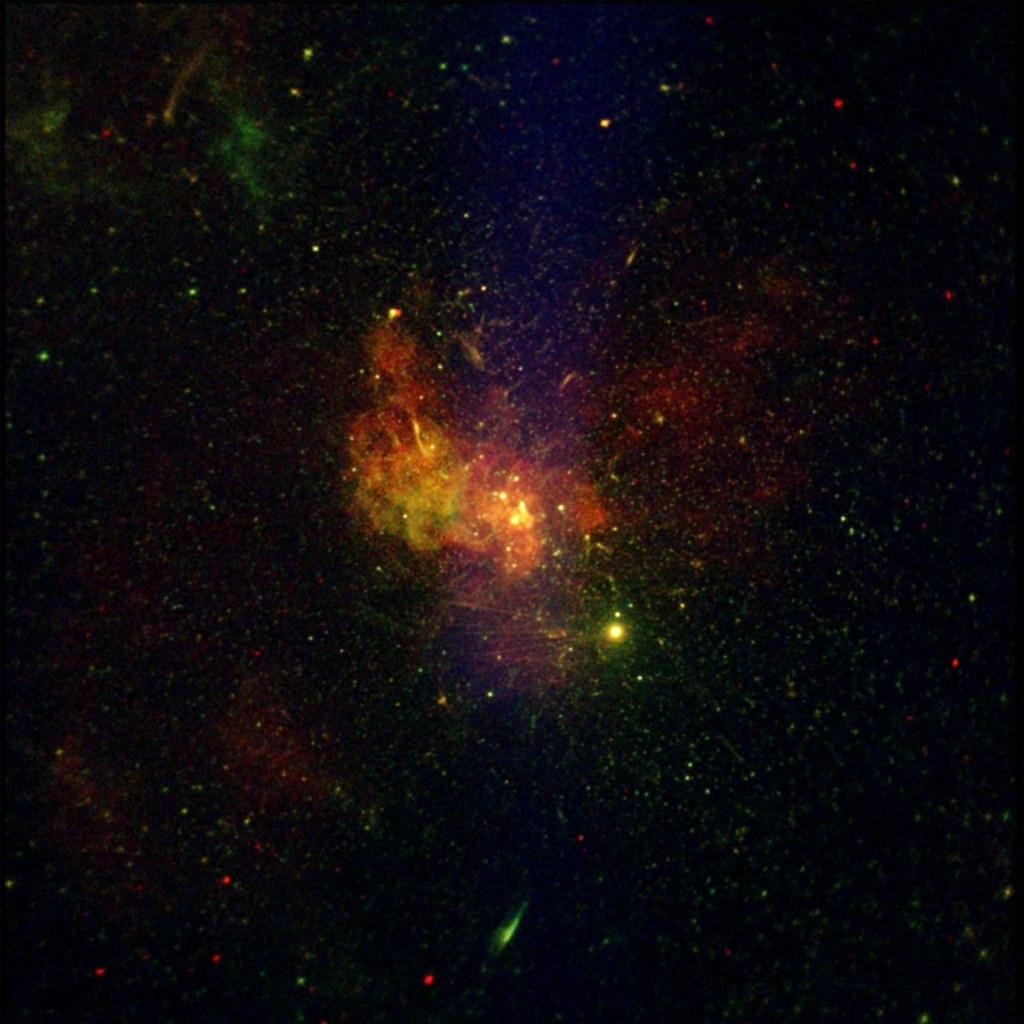

Since late 1997, Greenberg and his team, consisting of fellow professors to undergraduates, have been studying the images sent from the Galileo.

High-resolution images of the surface along with knowledge of Earth's geology have helped to reveal the environment of Europa.

One factor contributing to a habitable environment is the presence of liquid water, Greenberg said.

With Jupiter being the largest planet in the solar system, its tidal stresses on Europa create enough heat to keep the water on Europa in a liquid state.

This "opened the door to speculation about life," Greenberg said.

However, Greenberg points out that more than just water is needed to support life. Tides also play a role in providing for life.

Ocean tides on Europa are much greater in size than Earth's with heights reaching 500 meters (more than 1,600 feet). Even the shape of the moon is stretched along the equator due to Jupiter's pull on the waters below the icy surface.

"Everything on and under the surface is driven by the tides," Greenberg said.

The mixing of substances needed to support life is also driven by tides, he added.

"Stable environments are also necessary for life to flourish," he said.

Europa, whose orbit around Jupiter is in-synch with its rotation, is able to keep the same face towards the gas giant for thousands of years. But over longer periods of time, any given niche freezes, Greenberg said.

"That would require an organism to adapt in some way," he said.

The surface of Europa was previously thought to be tens kilometers thick, never exposing the oceans. Greenberg said the geologic structures are evidence that exposure occurs more commonly that ever thought.

"The ocean is interacting with the surface," Greenberg said. "There is a possible biosphere that extends from way below the surface to just above the crust."

Tides have created the two types of surface features seen on Europa: cracks/ridges and chaotic areas, Greenberg said.

The ridges are thought to be built over thousands of years by water seeping up the edges of cracks and refreezing to form higher and higher edges until the cracks close to form a new ridge.

The chaotic areas are thought to be evidence of the melt-through necessary for exposure to the oceans.

The tidal heat, created by internal friction, could be enough to melt the ice, he said.

Undersea volcanoes are also a possible explanation for large melt-throughs, he said.

Greenberg said this combination of factors would give organisms a stable but changing environment -exactly the type that would encourage evolution.

"Necessity drives change," Greenberg said.

The melted-through ice provides light and surface chemicals to the oceans, Greenberg said.

Life on Europa could resemble that of simple sea-dwelling organisms of Earth, Greenberg said, possibly utilizing photosynthesis for energy.

"Plenty of Earth's organisms live at 32 degrees (Fahrenheit) or below," he said.

Microbes, recently discovered in the Antarctic, can hibernate for up to a million years in the ice.

Europan organisms, trapped in the ice, could be thawed out when the next warm tide flowed through, effectively releasing them, Greenberg said.

While the Galileo spacecraft is almost finished with its mission, Greenberg is already poised for future missions. His team has two proposals on the table with NASA for the next orbiter to Jupiter and its moons, which is slated for sometime this decade. The decade after holds plans for a lander to Europa, if timetables hold.

Contact Information

Richard J. Greenberg

520-621-6940

greenberg@lpl.arizona.edu