5 min read

By Kate Ramsayer,

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

NASA is about to launch the agency’s most advanced laser instrument of its kind into space. The Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite-2, or ICESat-2, will provide critical observations of how ice sheets, glaciers and sea ice are changing, leading to insights into how those changes impact people where they live.

Launch is scheduled for Sept. 15, and as we count down the days, we’re counting up 10 things you should know about ICESat-2

There’s only one scientific instrument on ICESat-2, but it is a marvel. The Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System, or ATLAS, measures height by precisely timing how long it takes individual photons of light from a laser to leave the satellite, bounce off Earth, and return to the satellite. Hundreds of people at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, worked to build this smart-car-sized instrument to exacting requirements so that scientists can measure minute changes in our planet’s ice.

Not all ice is the same. Land ice, like the ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, or glaciers dotting the Himalaya, builds up as snow falls over centuries and forms compacted layers. When it melts, it can flow into the ocean and raise sea level. Sea ice, on the other hand, forms when ocean water freezes. It can last for years, or a single winter. When sea ice disappears, there is no effect on sea level (think of a melting ice cube in your drink), but it can change climate and weather patterns far beyond the poles.

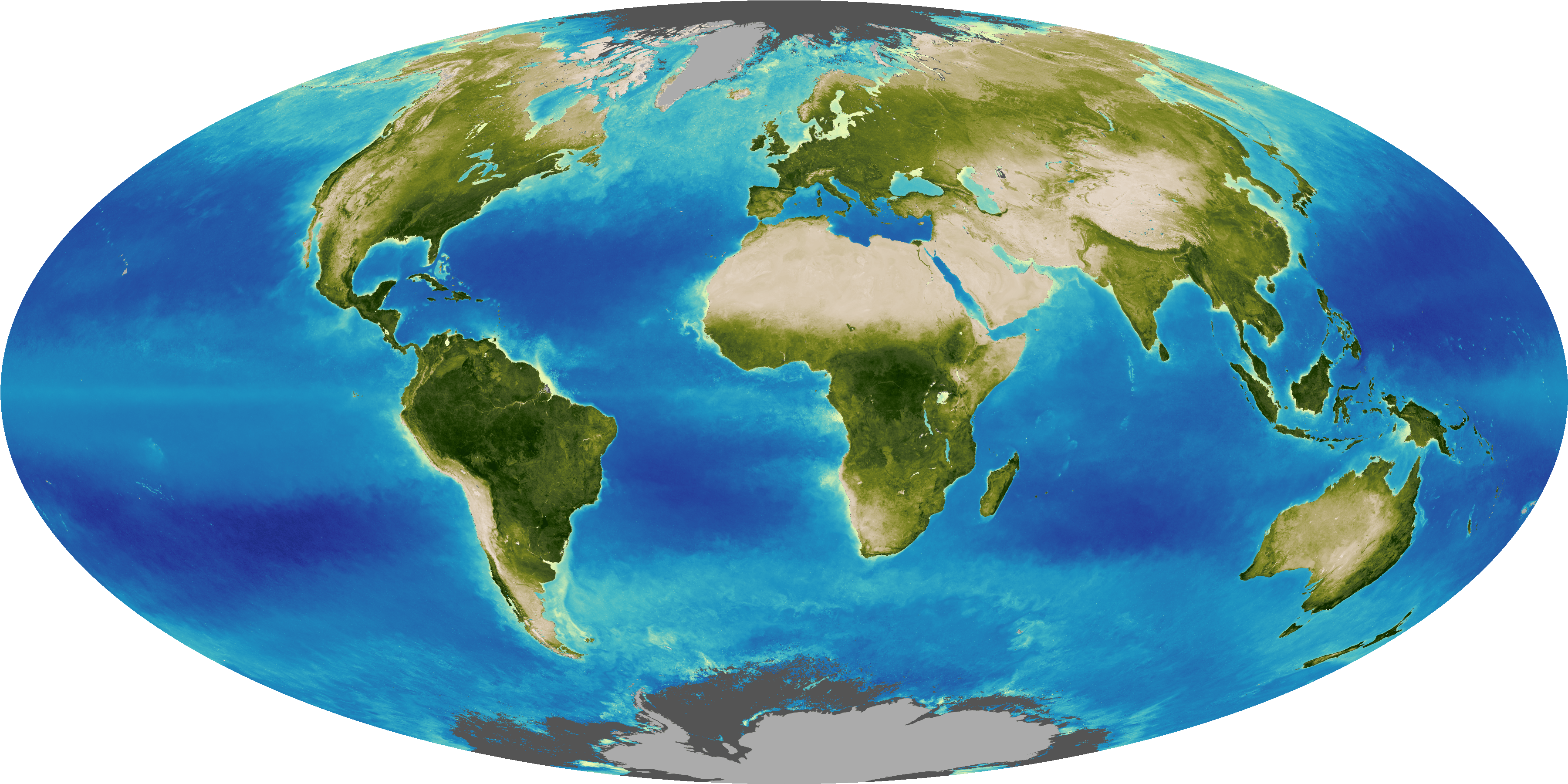

ICESat-2 will measure elevation to see how much glaciers, sea ice and ice sheets are rising or falling. NASA’s fleet of satellites collect detailed images of our planet that show the changing extent of features like ice sheets and forests, and with ICESat-2’s data, scientists can add the third dimension – height – to those portraits of Earth.

ICESat-2’s orbit will make 1,387 unique ground tracks around Earth in 91 days – and then start the same ground pattern again at the beginning. This allows the mission to measure the same ground tracks four times a year and scientists to see how glaciers and other frozen features change with the seasons – including over winter.

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/Ryan Fitzgibbons. Download this video in HD formats from NASA Goddard's Scientific Visualization Studio.

The ATLAS instrument will measure ice with a laser that shines at 532 nanometers – a bright green on the visible spectrum. When these laser photons return to the satellite, they pass through a series of filters that block any light that’s not exactly at this wavelength. This helps the instrument from being swamped with all the other shades of sunlight naturally reflected from Earth.

While the first ICESat satellite (2003-2009) measured ice with a single laser beam, ICESat-2 splits its laser light into six beams – the better to cover more ground (or ice). The arrangement of the beams into three pairs will also allow scientists to assess the slope of the surface they’re measuring.

ICESat-2 will zoom above the planet at 7 km per second (4.3 miles per second), completing an orbit around Earth in 90 minutes. The orbits have been set to converge at the 88-degree latitude lines around the poles, to focus the data coverage in the region where scientists expect to see the most change.

All of those height measurements result from timing the individual laser photons on their 600-mile roundtrip between the satellite and Earth’s surface – a journey that is timed to within 800 picoseconds. That’s a precision of less than a billionth of a second. NASA engineers had to custom build a stopwatch-like device, since no existing timers fit the strict requirements.

As ICESat-2 measures the poles, it adds to NASA’s record of ice heights that started with the first ICESat and continued with Operation IceBridge, an airborne mission that has been flying over the Arctic and Antarctic for nine years. The campaign, which bridges the gap between the two satellite missions, has flown since 2009, taking height measurements and documenting the changing ice.

ICESat-2’s laser will fire 10,000 times in one second. The original ICESat fired 40 times a second. More pulses mean more height data. If ICESat-2 flew over a football field, it would take 130 measurements between end zones; its predecessor, on the other hand, would have taken one measurement in each end zone.

ICESat-2’s fast-firing laser, combined with the instrument’s timing precision, sensitive photon-detection technology and other features will allow the ICESat-2 mission to measure the average annual change in vast ice sheets down to the width of a pencil.

For more information, visit icesat-2.gsfc.nasa.gov or nasa.gov/icesat-2.