Images captured by NASA’s Parker Solar Probe as the spacecraft made its record-breaking closest approach to the Sun in December 2024 have now revealed new details about how solar magnetic fields responsible for space weather escape from the Sun — and how sometimes they don’t.

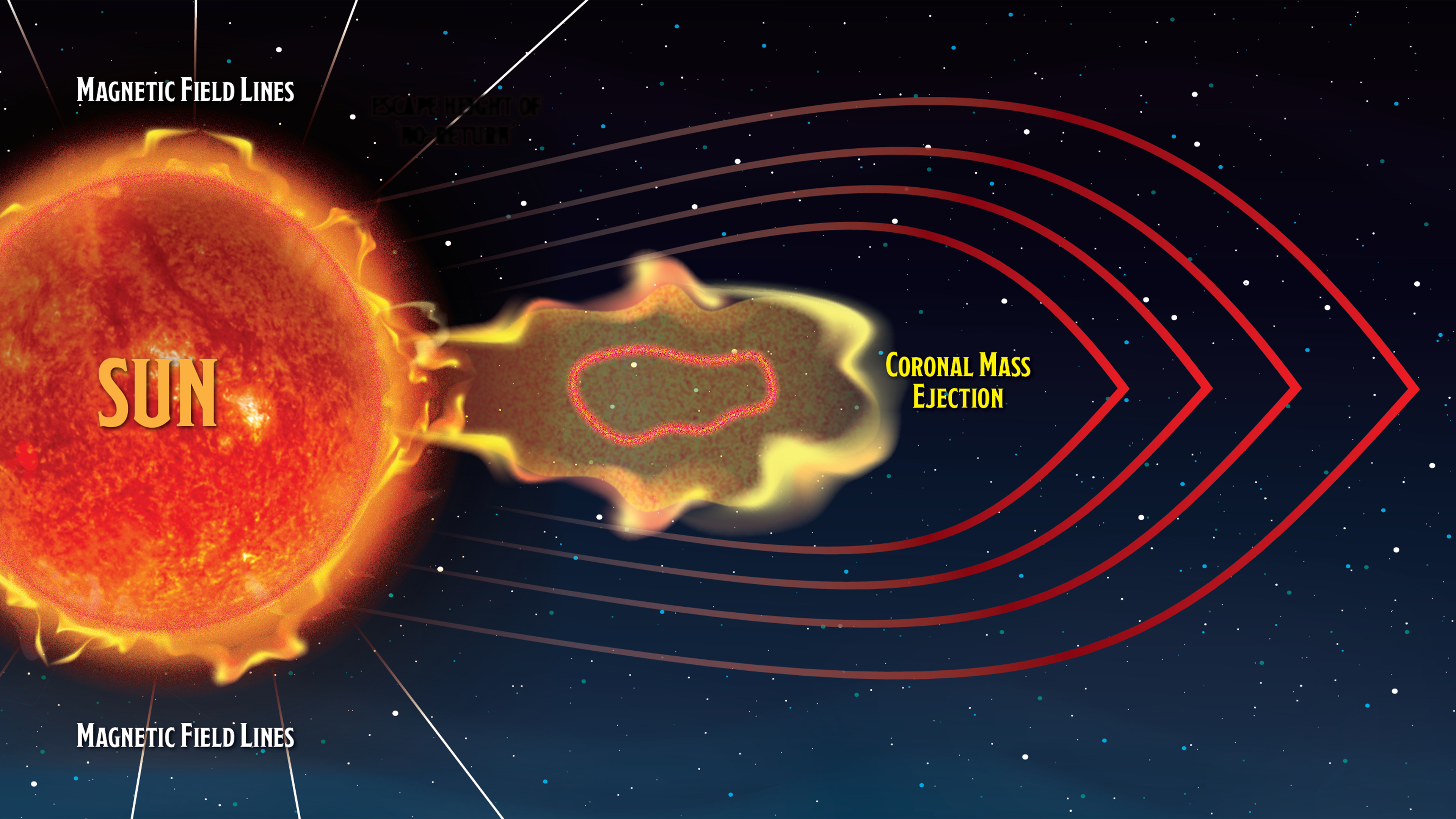

Like a toddler, our Sun occasionally has disruptive outbursts. But instead of throwing a fit, the Sun spews magnetized material and hazardous high-energy particles that drive space weather as they travel across the solar system. These outbursts can impact our daily lives, from disrupting technologies like GPS to triggering power outages, and they can also imperil voyaging astronauts and spacecraft. Understanding how these solar outbursts, called coronal mass ejections (CMEs), occur and where they are headed is essential to predicting and preparing for their impacts at Earth, the Moon, and Mars.

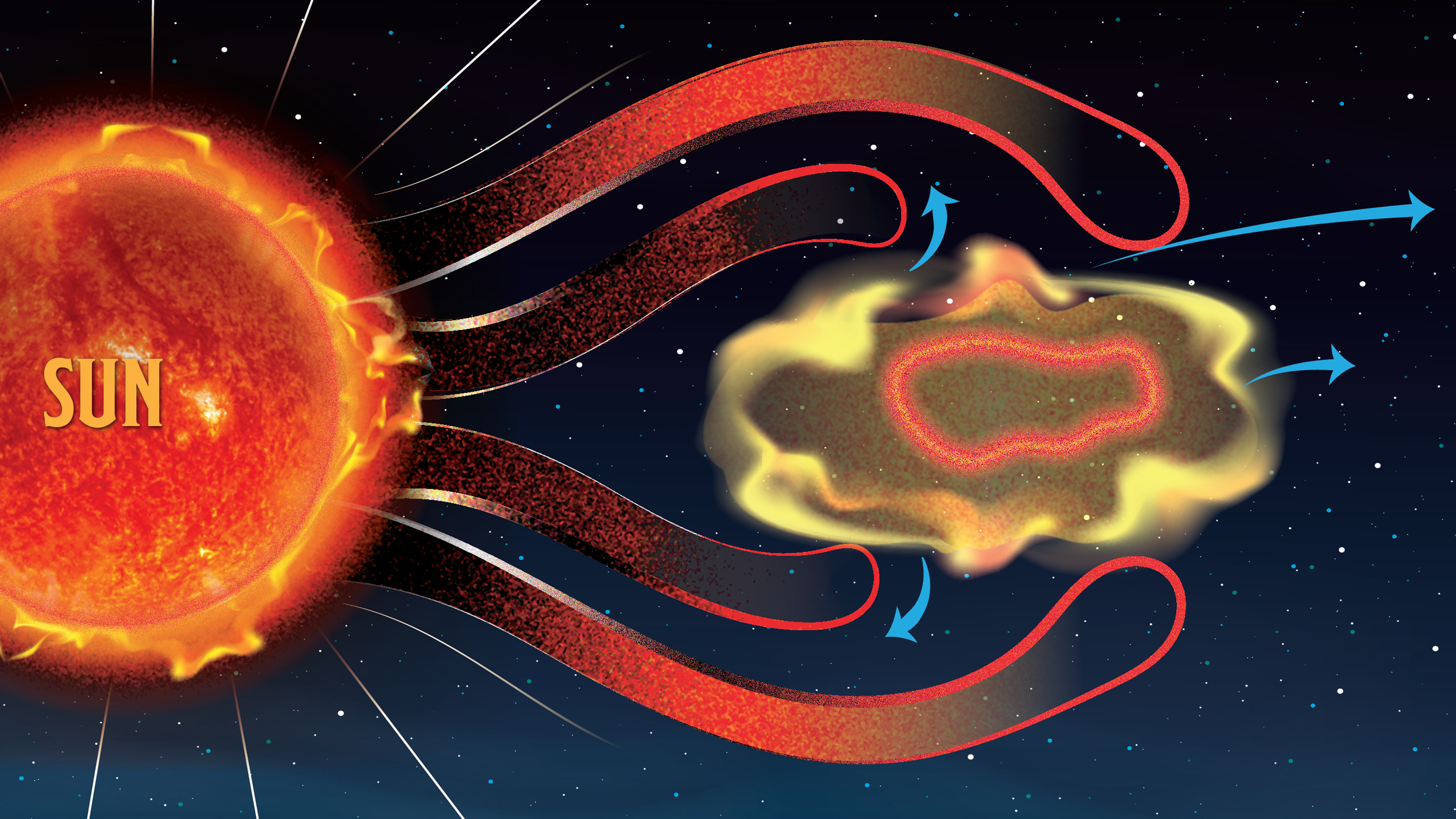

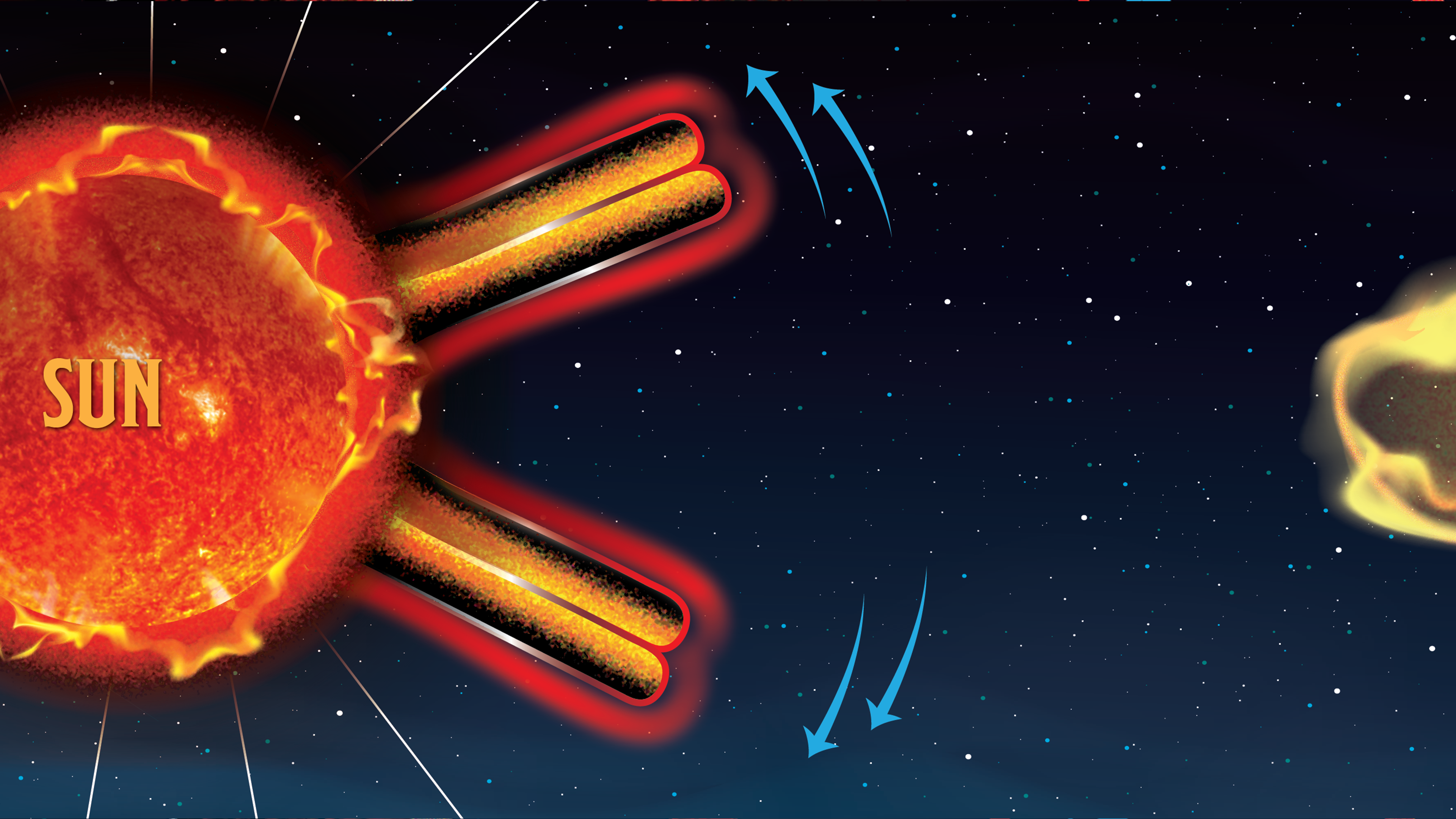

Images taken by Parker Solar Probe in December 2024, and published Thursday in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, have revealed that not all magnetic material in a CME escapes the Sun — some makes it back, changing the shape of the solar atmosphere in subtle, but significant, ways that can set the course of the next CME exploding from the Sun. These findings have far-reaching implications for understanding how the CME-driven release of magnetic fields affects not only the planets, but the Sun itself.

“These breathtaking images are some of the closest ever taken to the Sun and they’re expanding what we know about our closest star,” said Joe Westlake, heliophysics division director at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “The insights we gain from these images are an important part of understanding and predicting how space weather moves through the solar system, especially for mission planning that ensures the safety of our Artemis astronauts traveling beyond the protective shield of our atmosphere.”

Parker Solar Probe reveals solar recycling in action

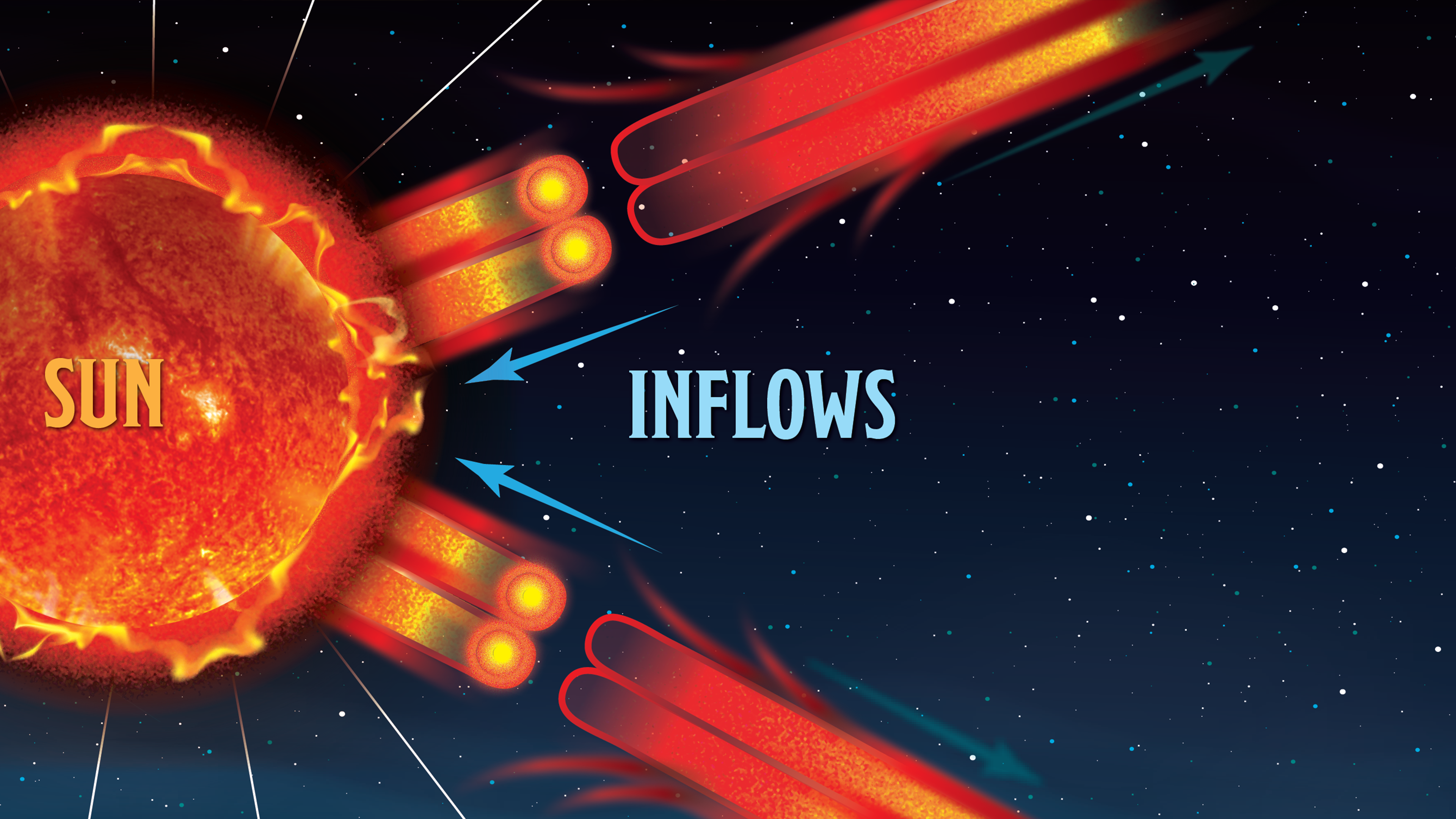

As Parker Solar Probe swept through the Sun’s atmosphere on Dec. 24, 2024, just 3.8 million miles from the solar surface, its Wide-Field Imager for Solar Probe, or WISPR, observed a CME erupt from the Sun. In the CME’s wake, elongated blobs of solar material were seen falling back toward the Sun.

This type of feature, called “inflows”, has previously been seen from a distance by other NASA missions including SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, a joint mission with ESA, the European Space Agency) and STEREO (Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory). But Parker Solar Probe’s extreme close-up view from within the solar atmosphere reveals details of material falling back toward the Sun and on scales never seen before.

“We’ve previously seen hints that material can fall back into the Sun this way, but to see it with this clarity is amazing,” said Nour Rawafi, the project scientist for Parker Solar Probe at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, which designed, built, and operates the spacecraft in Laurel, Maryland. “This is a really fascinating, eye-opening glimpse into how the Sun continuously recycles its coronal magnetic fields and material.”

Insights on inflows

For the first time, the high-resolution images from Parker Solar Probe allowed scientists to make precise measurements about the inflow process, such as the speed and size of the blobs of material pulled back into the Sun. These previously hidden details provide scientists with new insights into the physical mechanisms that reconfigure the solar atmosphere.