Why Study Moon Craters?

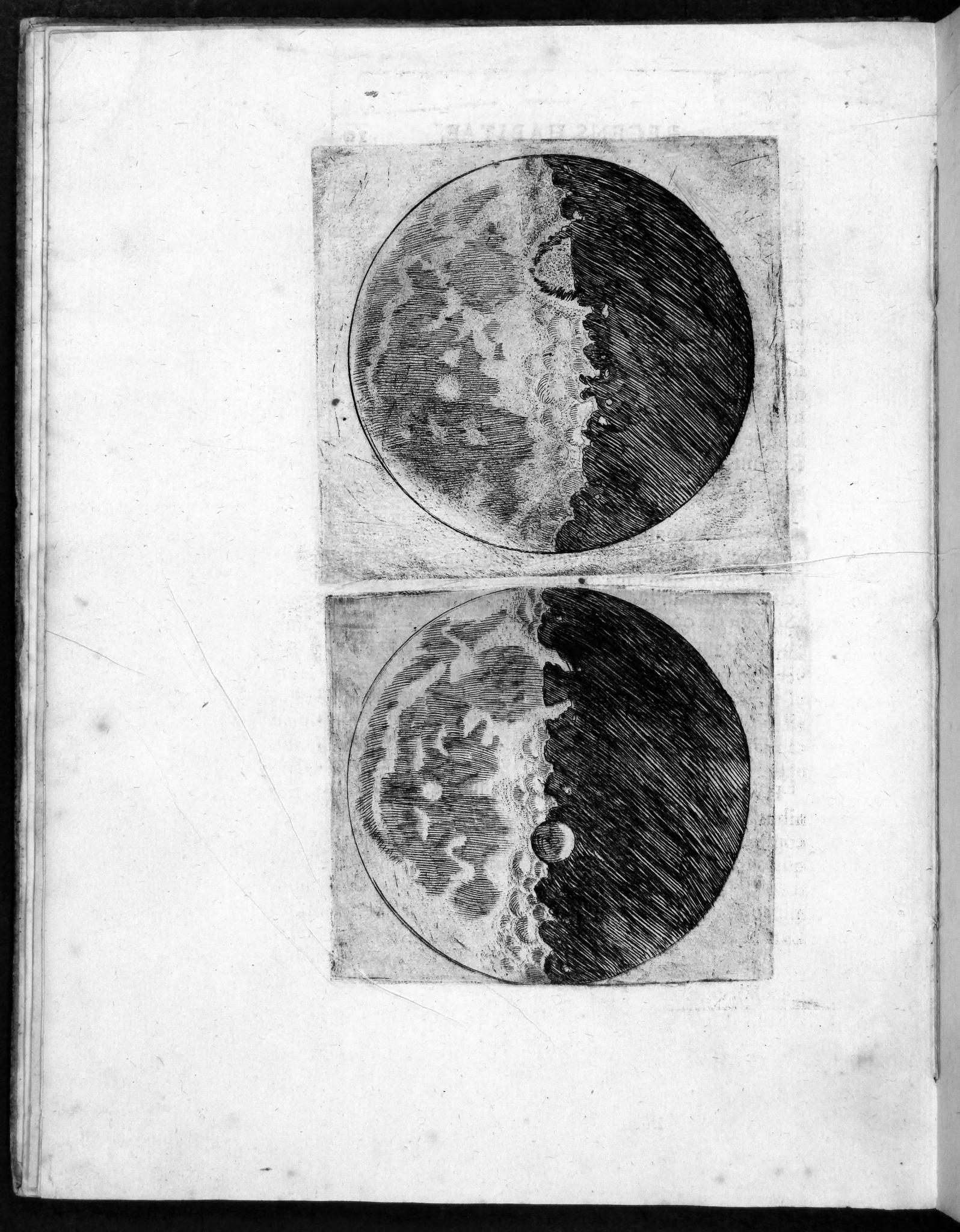

The Moon’s craters were among the first things Galileo observed upon turning his telescope on the skies, informing the world that the lunar surface was “full of hollows and protuberances, just like the surface of the Earth itself.”

Today’s scientists take a multipronged approach to studying impact craters: orbiting satellites, landers and even robotic explorers. They investigate lunar craters here on Earth through methods like examining and comparing terrestrial craters, computer modeling of impacts, and experiments with NASA’s Vertical Gun Range ― which fires projectiles at 7,000 to 15,000 miles per hour down a 14-foot tube into a dish of material meant to simulate the composition of the cosmic object it’s hitting.

Why all the effort? Because today, centuries after Galileo, we are still learning new things from studying the Moon’s craters.

-

What Can We Learn From a Hole?

Lunar craters tell us not only about the Moon’s history, but also about the history of the solar system. On the Moon, where there’s no liquid water or wind, evidence of our solar system’s impact history has been preserved for billions of years. On Earth, impact evidence is mostly obscured by processes like erosion, plate tectonics, and recent volcanic activity.

Typically, older areas on the lunar surface will have more craters, simply because they’ve had more time to be pelted with impactors like asteroids and comets. Scientists can tally how many or how few craters are in an area to get an idea of the age of the surface, a method called crater-counting. To make their estimates more precise, scientists combine crater-counting with other techniques, like studying Moon rocks' chemistry and analyzing spectroscopic data.

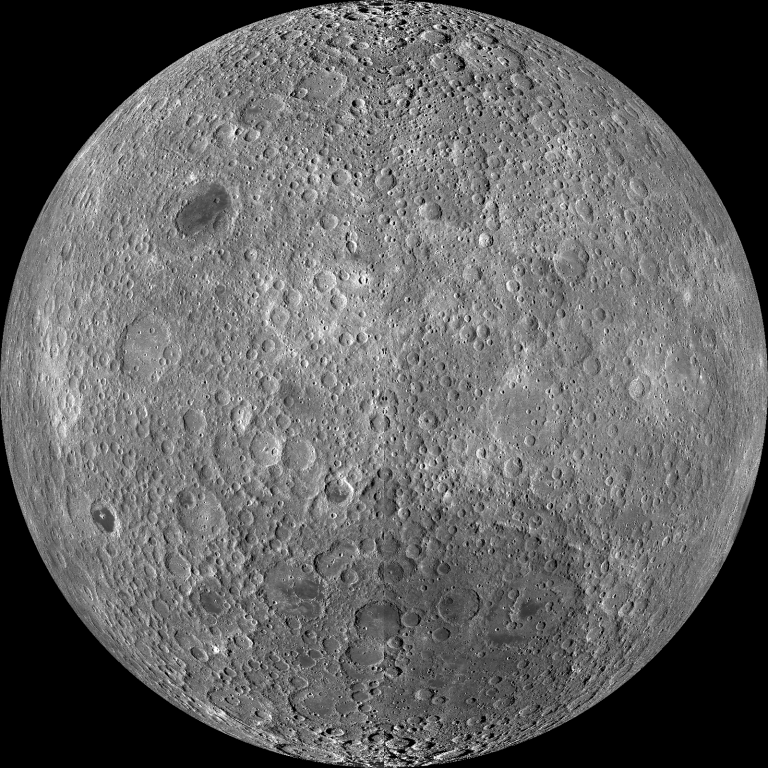

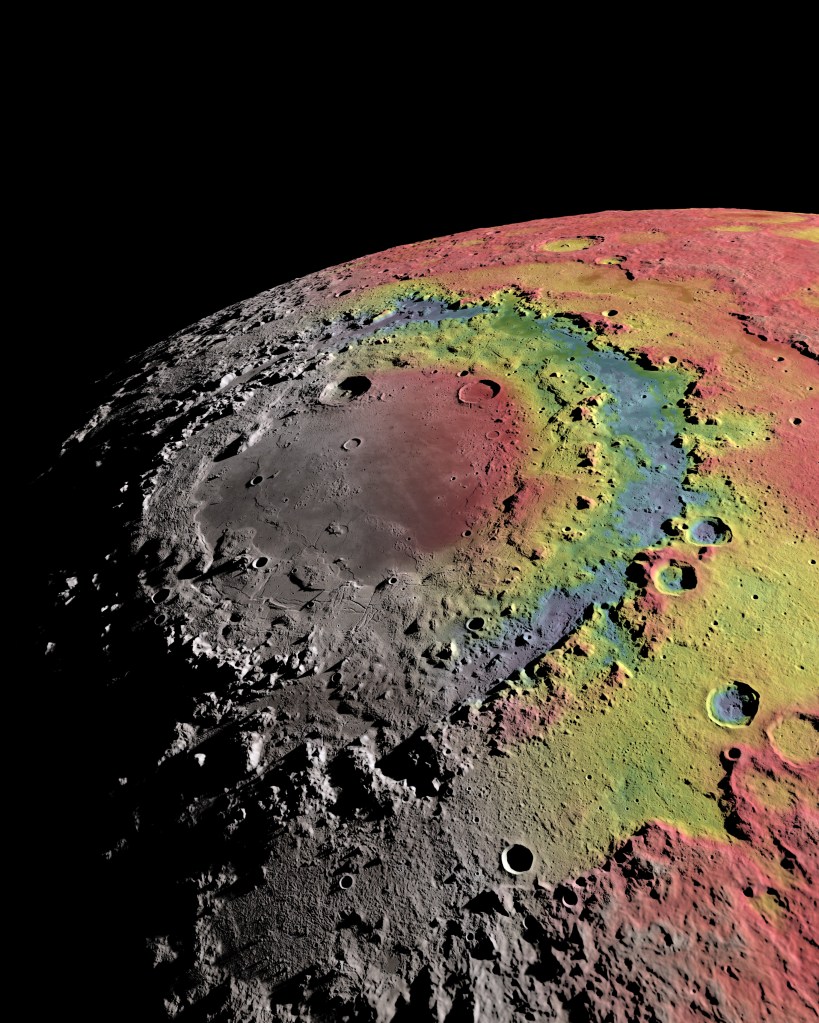

One of the Moon’s big mysteries is why its far side has relatively little volcanism compared to its nearside. Scientists are still working on that puzzle, but possibilities include differences in cooling rates on the young Moon’s near and far sides after its violent formation; a thicker crust on the far side preventing magma from emerging to fill craters; and a overturn of the lunar mantle early in its history focusing rare-earth and heat-producing elements to the near side of the Moon, causing increased volcanic activity there. Whatever the answer, the first sign that there was a discovery to be made was the striking presence of the myriad impact craters on the Moon’s far side. The Moon's far side has thicker crust, is heavily cratered, and lacks the prominent maria of the near side.NASA/Arizona State University

The Moon's far side has thicker crust, is heavily cratered, and lacks the prominent maria of the near side.NASA/Arizona State University -

Excavating Answers

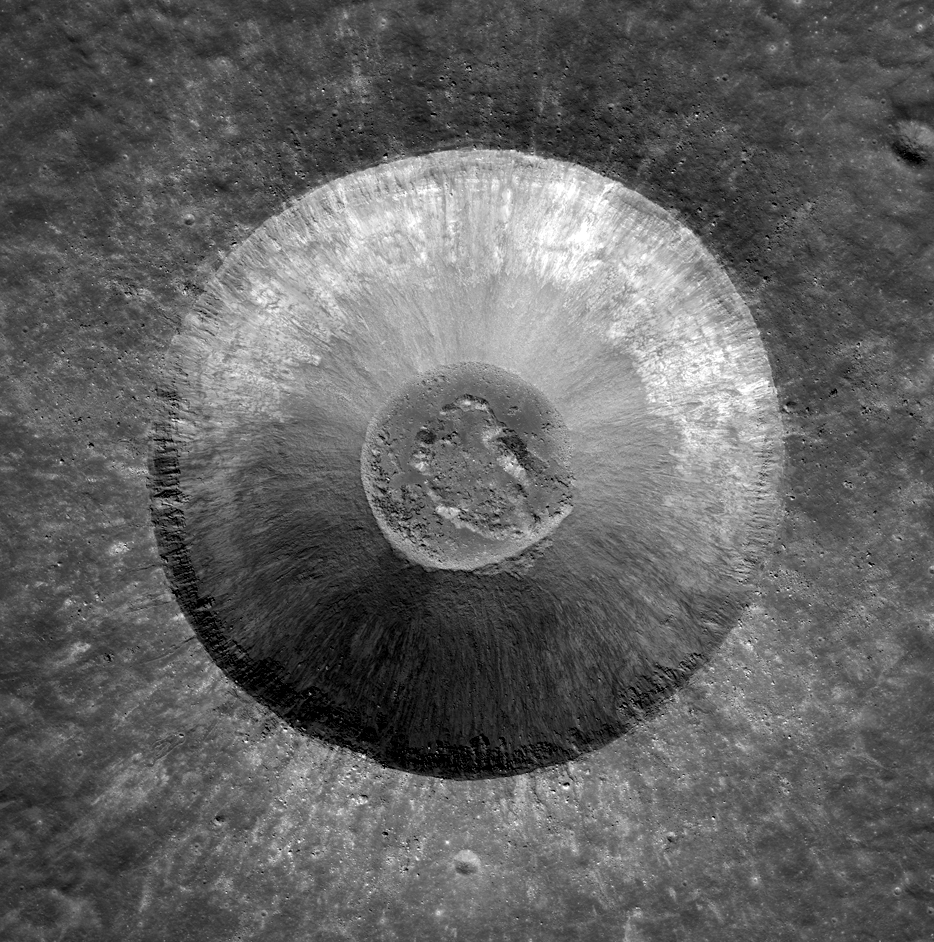

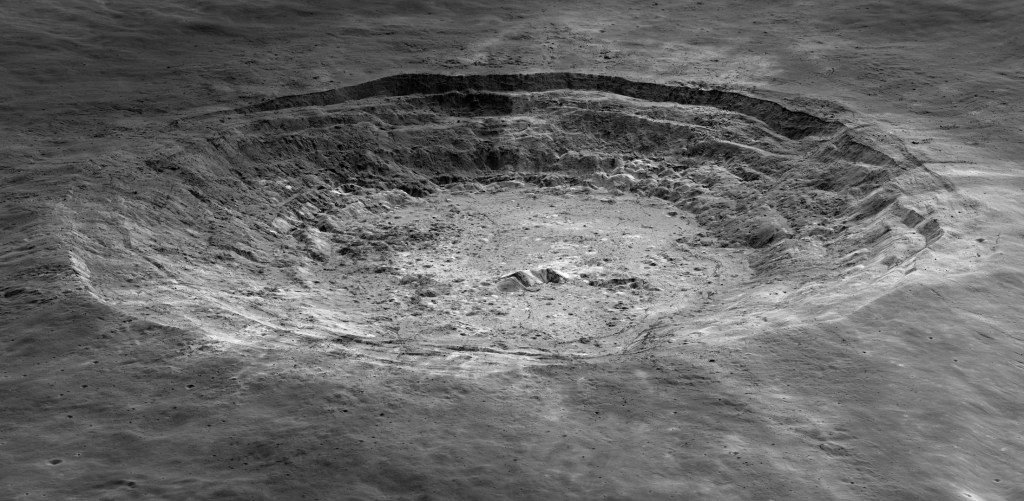

When impactors carve out portions of the Moon, they can give us a glimpse of the stuff that’s below the surface. Significant impactors explode material out from beneath the Moon’s surface, exposing it for study. For example, the Japanese lunar orbiter Kaguya has detected rings of olivine at the edges of major craters where the crust is thin, possibly a result of impactors breaking through the crust and dredging up material from the mantle or lower crust and pushing it toward the rims of the craters. Olivine is a big part of Earth’s mantle, and this may be evidence that it is a significant component of the Moon’s mantle as well.

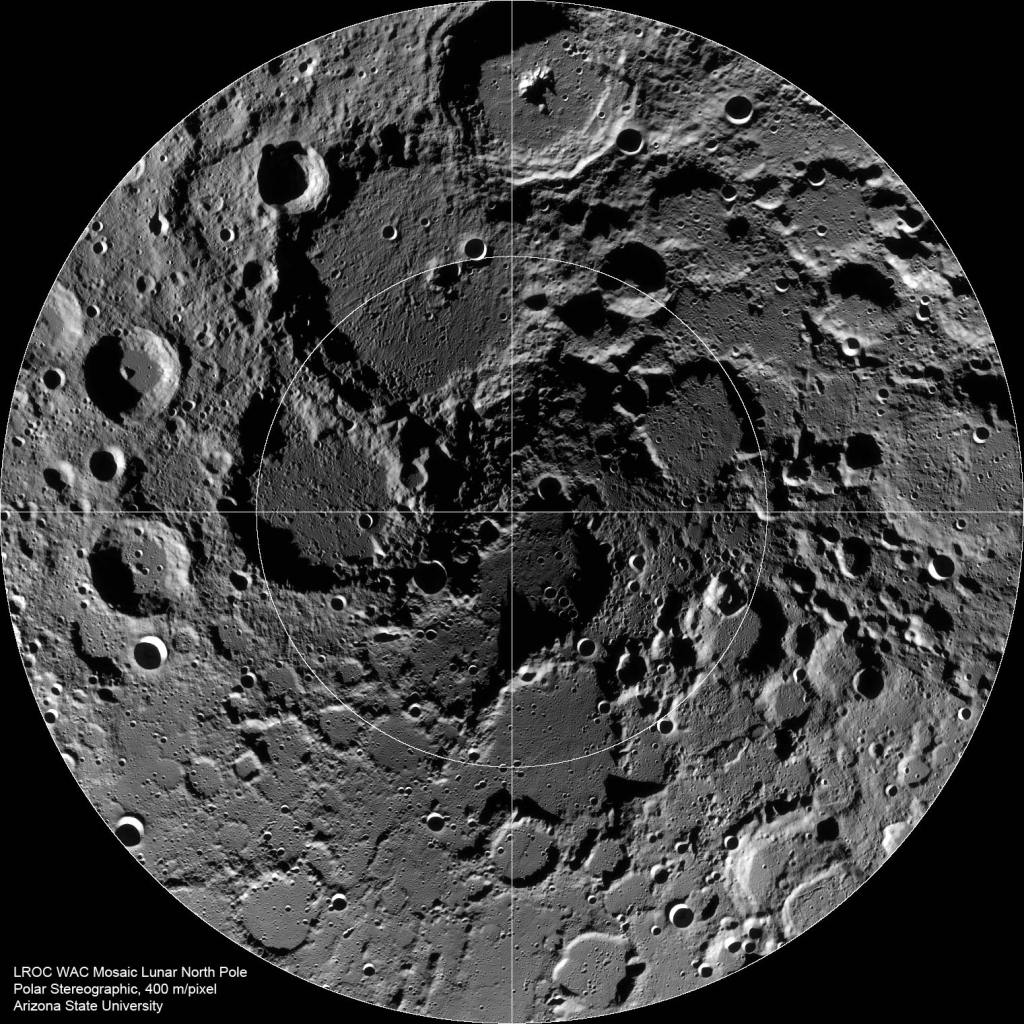

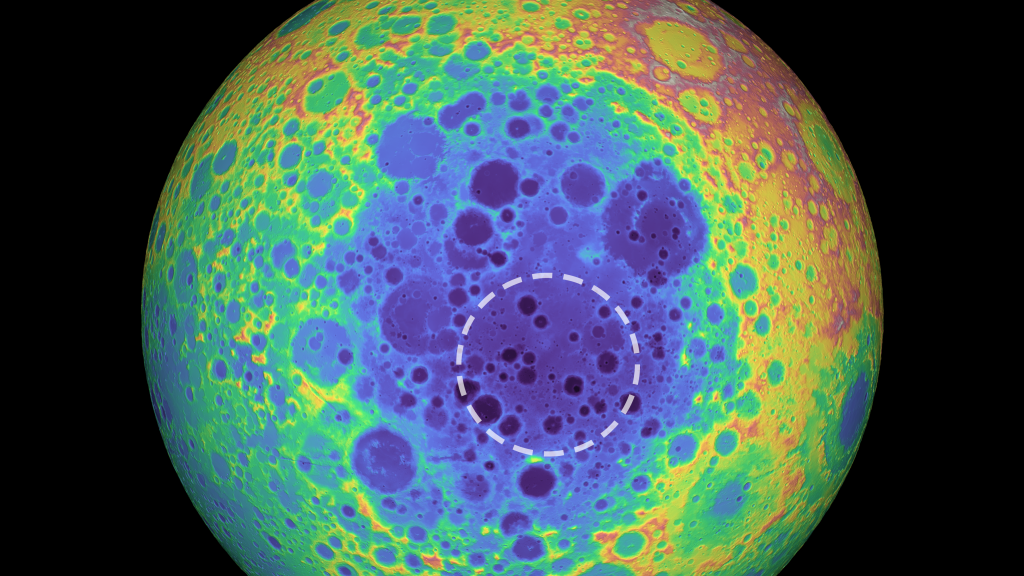

None of the Apollo samples were definitively identified as being pieces of the Moon’s mantle, but scientists believe such rocks should be found on the surface due to impacts, and have suggested regions to find these samples during future missions. The South Pole-Aitken Basin, the largest and deepest basin on the Moon, is a particularly attractive target because the impact that created it was so tremendous that scientists expect it to have pierced through the crust and into the mantle. This Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA) topographic map centers on the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) basin, the largest impact basin on the Moon and one of the largest impact basins in the solar system.NASA/GSFC/MIT

This Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA) topographic map centers on the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) basin, the largest impact basin on the Moon and one of the largest impact basins in the solar system.NASA/GSFC/MIT -

Look Out Above ― And Below

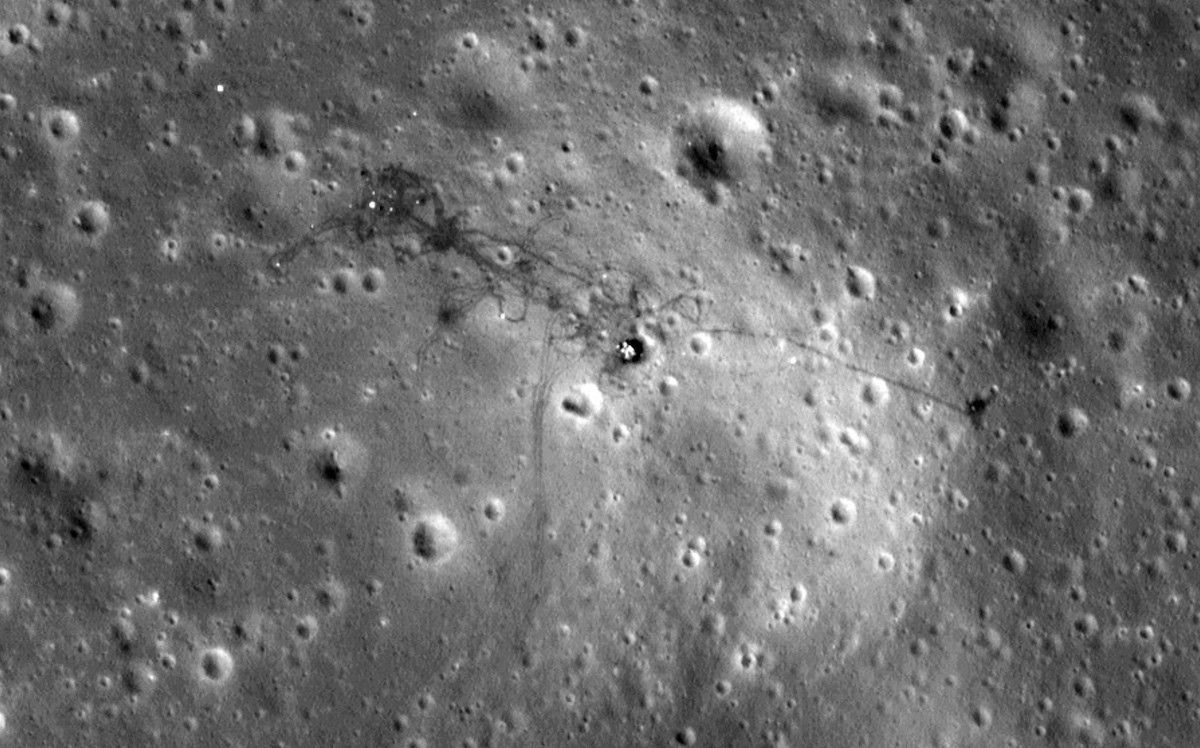

The study of lunar craters tells us much about problems astronauts may encounter when human beings return to the Moon. Scientists analyzing before and after pictures taken by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter found new craters forming on the Moon at a rate 33 percent higher than expected. This means that any equipment placed on the Moon for a long time ― like a lunar base ― would have to be able to withstand damage caused when nearby impacts spray debris that can move as fast as 1,600 feet per second (500 meters per second).

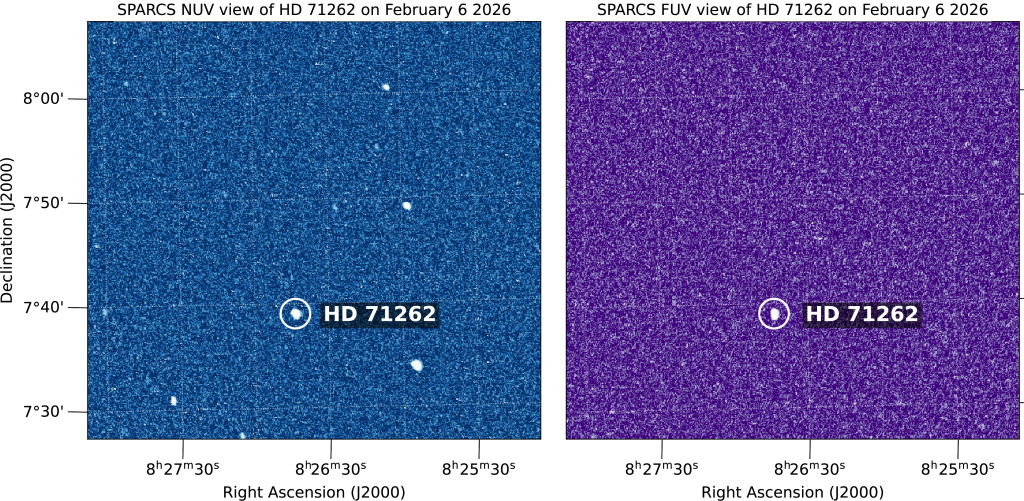

These images from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter show the birth of a new crater. The before and after pictures capture a 39-foot (12 meter) wide crater and its rays of ejecta appearing on the surface of the Moon. This duo of images show the birth of a new crater on the Moon. An impactor created a 39-foot-wide crater with rays of ejecta radiating away from it.NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

This duo of images show the birth of a new crater on the Moon. An impactor created a 39-foot-wide crater with rays of ejecta radiating away from it.NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

Writer: Tracy Vogel; Science Advisors: Daniel P. Moriarty (University of Maryland at College Park), Natalie M. Curran and Noah Petro (NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center)

All About Lunar Craters

Craters are the mark the passing universe leaves on the Moon, a cosmic guestbook. They tell us the history not only of the Moon, but of our solar system.

Learn More

Explore Further

Expand your knowledge about lunar craters.

What is the Late Heavy Bombardment?

Lunar craters give scientists a peek into our solar system’s asteroid-pummeled past.

The Explosive History of Orientale Basin

The Moon’s Orientale basin demonstrates the violence of a tremendous lunar impact.