Plume of Io

| PIA Number | PIA02588 |

|---|---|

| Language |

|

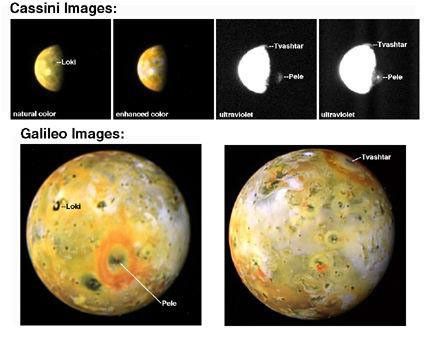

Galileo and Cassini Image Two Giant Plumes on Io

March 29, 2001

Two tall volcanic plumes and the rings of red material they have deposited

onto surrounding surface areas appear in images taken of Jupiter's moon Io

by NASA's Galileo and Cassini spacecraft in late December 2000 and early

January 2001.

A plume near Io's equator comes from the volcano Pele. It has been active

for at least four years, and has been far larger than any other plume seen

on Io, until now. The other, nearer to Io's north pole, is a Pele-sized

plume that had never been seen before, a fresh eruption from the Tvashtar

Catena volcanic area.

The observations were made during joint studies of the Jupiter system

while Cassini was passing Jupiter on its way to Saturn. The two craft

offered complementary advantages for observing Io, the most volcanically

active body in the solar system. Galileo passed closer to Io for

higher-resolution images, and Cassini acquired images at ultraviolet

wavelengths, better for detecting active volcanic plumes.

The Cassini ultraviolet images, upper right, reveal two gigantic, actively

erupting plumes of gas and dust. Near the equator, just the top of Pele's

plume is visible where it projects into sunlight. None of it would be

illuminated if it were less than 240 kilometers (150 miles) high. These

images indicate a total height for Pele of 390 kilometers (242 miles). The

Cassini image at far right shows a bright spot over Pele's vent. Although

the Pele hot spot has a high temperature, silicate lava cannot be hot

enough to explain a bright spot in the ultraviolet, so the origin of this

bright spot is a mystery, but it may indicate that Pele was unusually

active.

Also visible is a plume near Io's north pole. Although 15 active plumes

over Io's equatorial regions have been detected in hundreds of images from

NASA's Voyager and Galileo spacecraft, this is the first image ever

acquired of an active plume over a polar region of Io. The plume projects

about 150 kilometers (about 90 miles) over the limb, the edge of the

globe. If it were erupting from a point on the limb, it would be only

slightly larger than a typical Ionian plume, but the image does not reveal

whether the source is actually at the limb or beyond it, out of view.

A distinctive feature in Galileo images since 1997 has been a giant red

ring of Pele plume deposits about 1,400 kilometers (870 miles) in

diameter. The Pele ring is seen again in one of the new Galileo images,

lower left. When the new Galileo images were returned this month,

scientists were astonished to see a second giant red ring on Io, centered

around Tvashtar Catena at 63 degrees north latitude. (To see a comparison

from before the ring was deposited, see PIA-01604 or PIA-02309.) Tvashtar

was the site of an active curtain of high-temperature silicate lava imaged

by Galileo in November 1999 and February 2000 (image PIA-02584). The new

ring shows that Tvashtar must be the vent for the north polar plume imaged

by Cassini from the other side of Io! This means the plume is actually

about 385 kilometers (239 miles) high, just like Pele. The uncertainty in

estimating the height is about 30 kilometers (19 miles), so the plume

could be anywhere from 355 to 415 km (221 to 259 miles) high.

If this new plume deposit is just one millimeter (four one-hundredths of

an inch) thick, then the eruption produced more ash than the 1980 eruption

of Mount St. Helens in Washington.

NASA recently approved a third extension of the Galileo mission, including

a pass over Io's north pole in August 2001. The spacecraft's trajectory

will pass directly over Tvashtar at an altitude of 200 kilometers (124 miles).

Will Galileo fly through an active plume? That depends on whether

this eruption is long-lived, like Pele, or brief, and it also depends on

how high the plume is next August. Two Pele-sized plumes are inferred to

have erupted in 1979 during the four months between Voyager 1 and Voyager

2 flybys, as indicated by new Pele-sized rings in Voyager 2 images. Those

eruptions, both from high-latitude locations, were shorter-lived than

Pele, but their actual durations are unknown. Before its August flyby,

Galileo will get another more-distant look at Tvashtar in May.

It has been said that Io is the heartbeat of the jovian magnetosphere. The

two giant plumes evidenced in these images may have had significant

effects on the types, density and distribution of neutral and charged

particles in the Jupiter system during the joint observations of the

system by Galileo and Cassini from November 2000 to March 2001.

These Cassini images were acquired on Jan. 2, 2001, except for the frame

at the far right, which was acquired a day earlier. The Galileo images

were acquired on Dec. 30 and 31, 2000. Cassini was about 10 million

kilometers (6 million miles) from Io, ten times farther than Galileo.

More information about the Cassini and Galileo joint observations of the

Jupiter system is available online at:

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/jupiterflyby.

Cassini is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and

the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the

California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the Galileo and

Cassini missions for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, D.C.

For higher resolution, click here.