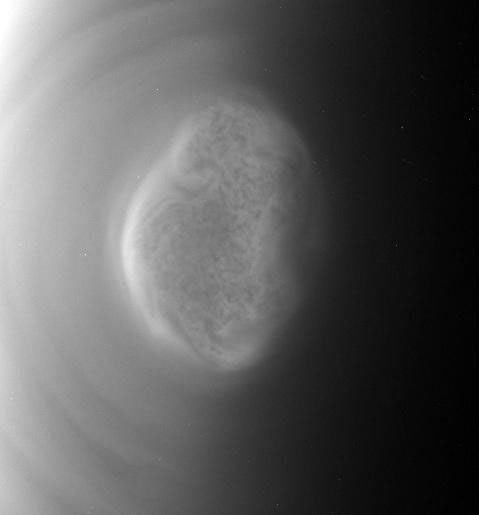

Titan’s South Polar Vortex in Motion

| PIA Number | PIA14920 |

|---|---|

| Language |

|

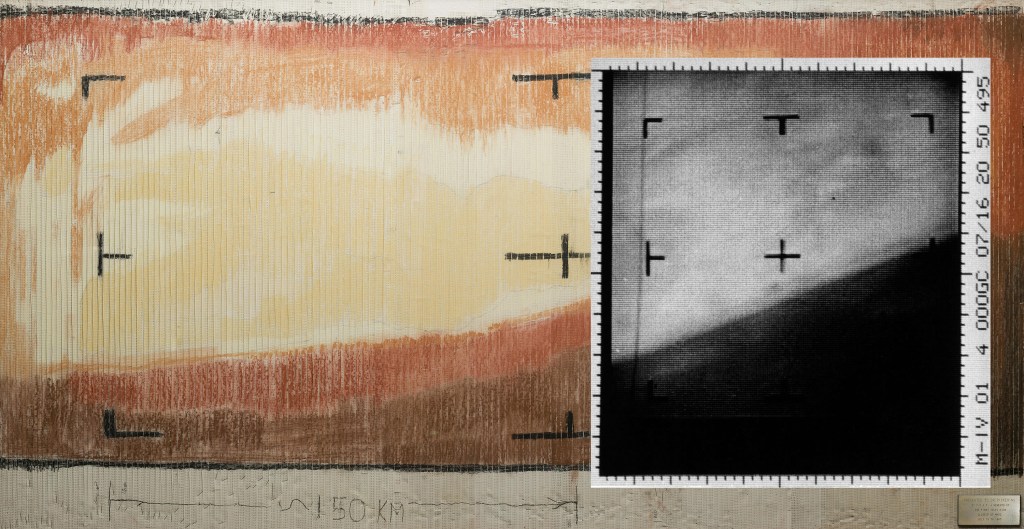

This movie captured by NASA'S Cassini spacecraft shows a south polar vortex, or a swirling mass of gas around the pole in the atmosphere, at Saturn’s moon Titan. The swirling mass appears to execute one full rotation in about nine hours – much faster than the moon's 16-day rotation period. The images were taken before and after a distant flyby of Titan on June 27, 2012.

The south pole of Titan (3,200 miles, or 5,150 kilometers, across) is near the center of the view.

Since Cassini arrived in the Saturn system in 2004, Titan has had a visible "hood" high above the north pole (see Haze Layers on Titan). It was northern winter at Cassini's arrival, and much of the high northern latitudes were in darkness. But the hood, an area of denser, high altitude haze compared to the rest of the moon's atmosphere, was high enough to still be illuminated by sunlight. The seasons have been changing since Saturn's August 2009 equinox signaled the beginning of spring in the northern hemisphere and fall in the southern hemisphere for the planet and its many moons. Now the high southern latitudes are moving into darkness. The formation of the vortex at Titan's south pole may be related to the coming southern winter and the start of what will be a south polar hood.

These new, more detailed images are only possible because of Cassini's newly inclined orbits, which are the next phase of Cassini Solstice Mission. Previously, Cassini was orbiting in the equatorial plane of the planet, and the imaging team's images of the polar vortex between late March and mid-May were taken from over Titan's equator. At that time, images showed a brightening or yellowing of the detached haze layer on the limb, or edge of the visible disk of the moon, over the south polar region.

See Titan's Colorful South Polar Vortex for a similar view in color.

Scientists think these new images show open cell convection. In open cells, air sinks in the center of the cell and rises at the edge, forming clouds at cell edges. However, because the scientists can't see the layer underneath the layer visible in these new images, they don't know what mechanisms may be at work.

Cosmic ray hits on the camera detectors appear as bright dots in some frames of the movie.

This movie is a concatenation of 10 images taken over a period of nine hours. The images were taken in visible blue light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera late on June 26 just before closest approach of the moon and early on June 27 as the spacecraft flew away from the moon. Each frame is separated by approximately one hour. The distance varies between 286,000 miles (461,000 kilometers) and 301,000 miles (484,000 kilometers), but the images were cropped and scaled to an image scale of 2 miles (3 kilometers) per pixel. The phase angle, or sun-Titan-spacecraft angle, decreases with time, from 111 degrees at the beginning to 95 degrees at the end.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov .

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute