Kuiper Belt Facts

The Kuiper Belt is a large, doughnut-shaped region of icy bodies extending far beyond the orbit of Neptune.

Introduction

The Kuiper Belt is located in the outer reaches of our solar system beyond the orbit of Neptune. It's sometimes called the "third zone" of the solar system. Astronomers think there are millions of small, icy objects in this region – including hundreds of thousands that are larger than 60 miles (100 kilometers) wide. Some of the objects, including Pluto, are over 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) wide. In addition to rock and water ice, objects in the Kuiper Belt also contain a variety of other frozen compounds like ammonia and methane.

Similar to the asteroid belt, the Kuiper Belt is a region of leftovers from the solar system's early history. Like the asteroid belt, it has also been shaped by a giant planet, although it's more of a thick disk (like a donut) than a thin belt.

The Kuiper Belt shouldn't be confused with the Oort Cloud, which is a much more distant region of icy, comet-like bodies that surrounds the solar system, including the Kuiper Belt. Both the Oort Cloud and the Kuiper Belt are thought to be sources of comets.

The Kuiper Belt is truly a frontier in space – it's a place we're still just beginning to explore and our understanding is still evolving.

Namesake

The region is named for astronomer Gerard Kuiper, who published a scientific paper in 1951 that speculated about objects beyond Pluto. Astronomer Kenneth Edgeworth also mentioned objects beyond Pluto in papers he published in the 1940s, and thus it's sometimes referred to as the Edgeworth-Kuiper Belt. Some researchers prefer to call it the Trans-Neptunian Region, and refer to Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs) as trans-Neptunian objects, or TNOs.

Whatever your preferred term is, the belt occupies an enormous volume in our solar system, and the small worlds that inhabit it have a lot to tell us about early history.

Size and Distance

The Kuiper Belt is one of the largest structures in our solar system – others being the Oort Cloud, the heliosphere, and the magnetosphere of Jupiter. Its overall shape is like a puffed-up disk or donut. Its inner edge begins at the orbit of Neptune, at about 30 AU from the Sun. (1 AU, or astronomical unit, is the distance from Earth to the Sun.) The inner, main region of the Kuiper Belt ends around 50 AU from the Sun. Overlapping the outer edge of the main part of the Kuiper Belt is a second region called the scattered disk, which continues outward to nearly 1,000 AU, with some bodies on orbits that go even farther beyond.

So far, more than 2,000 trans-Neptunian objects have been cataloged by observers, representing only a tiny fraction of the total number of objects scientists think are out there. In fact, astronomers estimate there are hundreds of thousands of objects in the region that are larger than 60 miles (100 kilometers) wide or larger. However, the total mass of all the material in the Kuiper Belt is estimated to be no more than about 10% of the mass of Earth.

Formation and Origins

Astronomers think the icy objects of the Kuiper Belt are remnants left over from the formation of the solar system. Similar to the relationship between the main asteroid belt and Jupiter, it's a region of objects that might have come together to form a planet had Neptune not been there. Instead, Neptune's gravity stirred up this region of space so much that the small, icy objects there weren't able to coalesce into a large planet.

The amount of material in the Kuiper Belt today might be just a small fraction of what was originally there. According to one well-supported theory, the shifting orbits of the four giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) could have caused most of the original material – likely 7 to 10 times the mass of Earth – to be lost.

The basic idea is that early in the solar system's history, Uranus and Neptune were forced to orbit farther from the Sun due to shifts in the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn. As Uranus and Neptune drifted farther outward, they passed through the dense disk of small, icy bodies left over after the giant planets formed. Neptune's orbit was the farthest out, and its gravity bent the paths of countless icy bodies inward toward the other giants. Jupiter ultimately slingshotted most of these icy bodies either into extremely distant orbits (to form the Oort Cloud) or out of the solar system entirely. As Neptune tossed icy objects sunward, this caused its own orbit to drift even farther out, and its gravitational influence forced the remaining icy objects into the range of locations where we find them in the Kuiper Belt.

Today the Kuiper Belt is slowly eroding away. Objects that remain there occasionally collide, producing smaller objects fragmented by the collision, sometimes comets and also dust that's blown out of the solar system by the solar wind.

Structure and Characteristics

The Kuiper Belt is an enormous, donut-shaped volume of space in the outer solar system. While there are many icy bodies in this region that we broadly refer to as Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) or trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs), they're fairly diverse in size, shape, and color. And importantly, they're not evenly distributed through space – once astronomers started discovering them in the early 1990s, one of the early surprises was that KBOs could be grouped according to the shapes and sizes of their orbits. This led scientists to understand that there are several distinct groupings, or populations, of these objects whose orbits provide clues about their history. Which category an object belongs to has a lot to do with how it has interacted with the gravity of Neptune over time.

Most of the objects in the Kuiper Belt are found in the main part of the belt itself or in the scattered disk:

Classical KBOs

A large fraction of KBOs orbit the Sun in what's called the classical Kuiper Belt. The term "classical" refers to the fact that, among the KBOs, these objects have orbits most similar to the original, or classical, idea of what the Kuiper Belt was expected to be like before astronomers started actually finding objects there. (The expectation was that, if there were objects beyond Neptune, they would be in relatively circular orbits that aren't tilted too much from the plane of the planets. Instead, many KBOs are found to have significantly elliptical and tilted orbits. Thus, to some extent, the classification of KBOs still reflects our evolving understanding of this distant region of the solar system.)

There are two main groups of objects in the classical Kuiper Belt, referred to as "cold" and "hot." These terms don't refer to temperature – instead, they describe the orbits of the objects, along with the amount of influence Neptune's gravity has had on them.

All classical KBOs have a similar average distance from the Sun between about 40 and 50 AU. Cold classical KBOs have relatively circular orbits that are not tilted much away from the plane of the planets; hot classical KBOs have more elliptical and tilted orbits (which astronomers refer to as eccentric and inclined, respectively). This means the cold variety spend most of their time at about the same distance from the Sun, while the hot ones wander over a larger range of distances from the Sun (meaning, in some parts of their orbits, they are closer to the Sun and sometimes they are farther away).

The differences between these two types of bodies in the classical Kuiper Belt have everything to do with Neptune. The cold classical KBOs have orbits that never come very close to Neptune, and thus they remain "cool" and unperturbed by the giant planet's gravity. Their orbits likely haven't moved much for billions of years. In contrast, the hot classical KBOs have had interactions with Neptune in the past (that is, with the giant planet's gravity). These interactions pumped energy into their orbits, which stretched them into an elliptical shape, and tilted them slightly out of the plane of the planets.

Resonant KBOs

A significant number of KBOs are in orbits that are tightly controlled by Neptune. They orbit in resonance with the giant planet, meaning their orbits are in a stable, repeating pattern with Neptune's. These resonant KBOs complete a specific number of orbits in the same amount of time that Neptune completes a specific number of orbits (in other words, a ratio). There are several of these groupings, or resonances – 1:1 (pronounced "one to one"), 4:3, 3:2, and 2:1. For example, Pluto is in a 3:2 resonance with Neptune, meaning it circles the Sun twice for every three times Neptune goes around.

In fact, there are enough objects on orbits with this 3:2 resonance, along with Pluto, that astronomers have given them their own category among the resonant KBOs: the plutinos.

Scattered Disk

The scattered disk is a region that stretches far beyond the main part of the Kuiper Belt. It is home to objects that have been scattered by Neptune into orbits that are highly elliptical and highly inclined to the plane of the planets. Many scattered disk objects have orbits that are tilted by tens of degrees. Some venture hundreds of AU from the Sun and high above the plane of the planets at the farthest point in their orbits, before falling back to a closest point near the orbit of Neptune. The orbits of many objects in the scattered disk are still slowly evolving, with objects here being lost over time, compared to the classical Kuiper Belt, where orbits are more stable.

The scattered disk gives the donut-shaped classical Kuiper Belt a much wider and thicker extent. Some astronomers talk about the two as separate regions, although their boundaries overlap and are linked together in a number of ways. In particular, the objects in both regions are thought to have ended up there as a result of the migration of Neptune from its original, closer orbit to where it is now.

Eris is an example of an object in the scattered disk and is the largest known member of this population.

Additional Families

Most of the objects in the Kuiper Belt are found in the main part of the belt or in the scattered disk, but there are also a couple of additional families of objects that orbit the Sun interior and exterior to the belt. These additional groups of objects probably came from the Kuiper Belt originally, but have been pulled out of the main regions by the gravity of Neptune or perhaps by another massive planet.

Detached Objects

Detached Kuiper Belt objects have orbits that never come closer to the Sun than about 40 AU. This sets them apart from most other KBOs, which spend at least part of their orbits in the region between 40 and 50 AU from the Sun. Because their orbits don't come close to Neptune's distance from the Sun (~30 AU), detached objects seem unlikely to have been pulled out of the Kuiper Belt by interactions with the giant planet. Scientists think it's likely some other force is responsible, such as an undiscovered giant planet (in a very distant orbit), the gravity of passing stars, or gravitational perturbations as the Kuiper Belt was forming long ago.

Sedna is an example of a detached KBO. The closest it comes to the Sun is 76 AU, while at its farthest it travels out to ~1200 AU.

Centaurs

Centaurs are objects with orbits that travel through the space between the orbits of Jupiter and Neptune. Objects in these orbits interact strongly with the gravity of the giant planets. Because of these powerful gravitational encounters, most are fated to either be ejected from the solar system or pushed into the inner solar system where they become comets or crash into the Sun and planets.

This process – the removal of the Centaurs – is ongoing, taking tens of millions of years for the typical Centaur object. Thus, the fact that there are Centaurs around today is evidence that they're being actively supplied from somewhere else. Astronomers think the most likely explanation is that they're relatively recent escapees from the Kuiper Belt. In fact, Centaurs are understood to be scattered objects, like those in the scattered disk – the difference being that the Centaurs have been scattered closer to the Sun by Neptune, rather than farther out.

Pluto's Place in the Kuiper Belt

In 1930, Pluto became the first Kuiper Belt object to be discovered. It was found at a time before astronomers had reason to expect a large population of icy worlds beyond Neptune. Today it's known as the "King of the Kuiper Belt" – and it's the largest object in the region, even though another object similar in size, called Eris, has a slightly higher mass. Pluto’s orbit is said to be in resonance with the orbit of Neptune, meaning Pluto's orbit is in a stable, repeating pattern with Neptune's. For every three orbits completed by Neptune, Pluto makes two orbits. In this situation, Pluto never comes close enough to Neptune to be affected much by its gravity. In fact, even though its orbit crosses Neptune's orbit, Pluto gets physically closer to Uranus than it ever does to Neptune.

Kuiper Belt Moons and Binaries

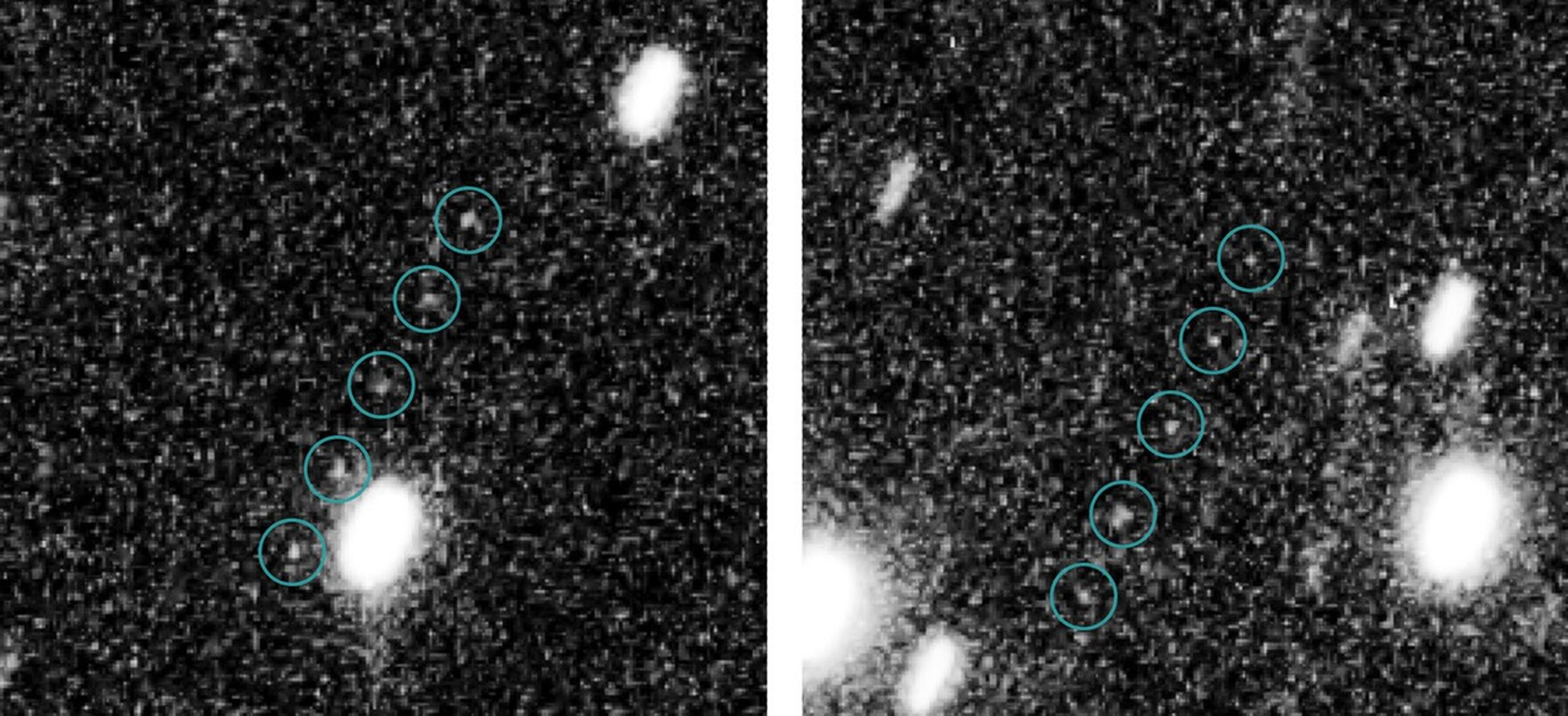

A fairly large number of KBOs either have moons – that is, significantly smaller bodies that orbit them – or are binary objects. Binaries are pairs of objects that are relatively similar in size or mass that orbit around a point – a shared center of mass – that lies between them. Some binaries actually touch, creating a sort of peanut shape, creating what's known as a contact binary.

The small Kuiper Belt Object called Arrokoth is a contact binary. It was discovered in 2014 by NASA’s New Horizons science team, using the Hubble Space Telescope. NASA's New Horizons spacecraft flew by Arrokoth on Jan. 1, 2019, snapping images that showed a double-lobed object that looked like a partially flattened red snowman. Arrokoth is the most distant and the most primitive object ever explored by a spacecraft.

Dwarf planets Pluto, Eris, Haumea, and Makemake are all Kuiper Belt objects that have moons.

One thing that makes binary KBOs particularly interesting is that most of them may be extremely ancient, or primordial, objects that have been altered little since their formation. The various ideas for how these pairs form require a lot more objects than the present-day Kuiper Belt appears to contain. One leading idea is that binaries may result from low-speed collisions between KBOs, which would allow them to survive the impact and stick together due to their mutual gravity. Such collisions were likely much more common billions of years ago when most KBOs were on similar orbits that were more circular and close to the plane of the planets (called the ecliptic). Today such collisions are much rarer. They also tend to be destructive, since lots of KBOs are on now orbits that are tilted or elliptical, meaning they crash into each other with greater force and break apart.

Relationship to Comets

The Kuiper Belt is a source of comets, but not the only source. Today the Kuiper Belt is thought to be very slowly eroding itself away. Objects there occasionally collide, with the collisional fragments producing smaller KBOs (some of which may become comets), as well as dust that's blown out of the solar system by the solar wind. Pieces produced by colliding KBOs can be pushed by Neptune's gravity into orbits that send them sunward, where Jupiter further corrals them into short loops lasting 20 years or less. These are called short-period Jupiter-family comets. Given their frequent trips into the inner solar system, most tend to exhaust their volatile ices fairly quickly and eventually become dormant, or dead, comets with little or no detectable activity.

Researchers have found that some near-Earth asteroids are actually burned-out comets, and most of them would have started out in the Kuiper Belt. Many comets crash into the Sun or the planets. Those that have close encounters with Jupiter tend to be ripped apart or tossed out of the solar system entirely.

The other source of comets is the Oort Cloud, where most long-period comets on highly tilted orbits come from.