The Definition of a Planet

The word goes back to the ancient Greek word planēt, and it means "wanderer."

A more modern definition can be found in the Merriam-Webster dictionary which defines a planet as "any of the large bodies that revolve around the Sun in the solar system."

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) - a group of astronomers that names objects in our solar system - agreed on their own definition of the word "planet." This new definition changed caused Pluto's famous "demotion" to a dwarf planet.

The definition of a planet adopted by the IAU says a planet must do three things:

- It must orbit a star (in our cosmic neighborhood, the Sun).

- It must be big enough to have enough gravity to force it into a spherical shape.

- It must be big enough that its gravity has cleared away any other objects of a similar size near its orbit around the Sun.

An Evolving Definition

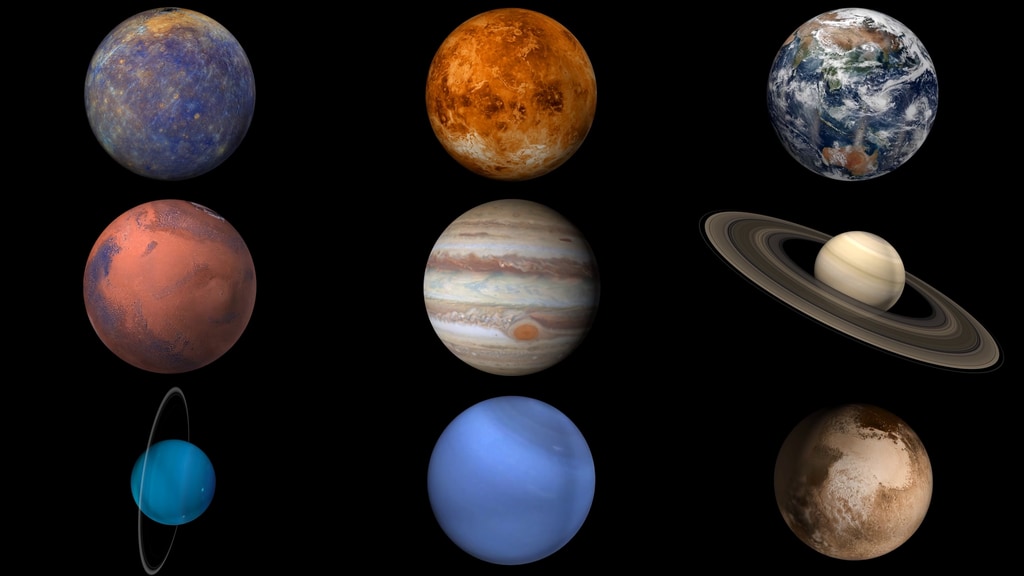

When the ancient Greeks came up with their definition of planets, they counted Earth's Moon, and Sun as planets along with Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Interestingly, Earth was not considered a planet, but rather was thought to be the central object around which all the other celestial objects orbited.

The first known model that placed the Sun at the center of the known universe with the Earth revolving around it was presented by Aristarchus of Samos in the third century BCE, but it was not generally accepted. It wasn't until the 16th century that the idea was revived by Nicolaus Copernicus.

By the 17th century, astronomers (aided by the invention of the telescope) realized that the Sun was the celestial object around which all the planets – including Earth – orbit, and that the Moon is not a planet, but a satellite of Earth. Uranus was added as a planet in 1781 and Neptune was discovered in 1846.

Ceres was discovered between Mars and Jupiter in 1801, and it was originally classified as a planet. But as more objects were found in the same region, Ceres was considered to be the first of a class of similar objects that were eventually termed asteroids (star-like) or minor planets.

Pluto, discovered in 1930, was identified as the ninth planet. But Pluto is much smaller than Mercury and is even smaller than some of the planetary moons. It is unlike the terrestrial planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars), or the gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn), or the ice giants (Uranus, Neptune). Charon, its huge satellite, is nearly half the size of Pluto and shares Pluto's orbit. Though Pluto kept its planetary status through the 1980s, things began to change in the 1990s with some new discoveries.

Technical advances in telescopes led to the detection of very small, very distant objects. In the early 1990s, astronomers began finding numerous icy worlds orbiting the Sun in a doughnut-shaped region called the Kuiper Belt beyond the orbit of Neptune – out in Pluto's realm. With the discovery of the Kuiper Belt and its thousands of icy bodies (known as Kuiper Belt Objects, or KBOs; also called trans-Neptunians), it was proposed that it is more useful to think of Pluto as the biggest KBO instead of a planet.

The Planet Debate

In 2005, a team of astronomers announced that they had found a tenth planet – it was a KBO similar in size to Pluto. People began to wonder what planethood really means. Just what is a planet, anyway? Suddenly the answer to that question didn't seem so self-evident, and, as it turns out, there are plenty of disagreements about it.

The IAU took on the challenge of classifying the newly found KBO, which later was named Eris. In 2006, the IAU passed a resolution that defined the term planet. It also established a new category called dwarf planet. Eris, Ceres, Pluto, and two more recently discovered KBOs named Haumea and Makemake, are the dwarf planets recognized by the IAU. There may be another 100 dwarf planets in the solar system, and hundreds more in and just outside the Kuiper Belt.

The New Definition of Planet

Here is the text of the IAU’s Resolution B5: Definition of a Planet in the Solar System:

"Contemporary observations are changing our understanding of planetary systems, and it is important that our nomenclature for objects reflect our current understanding. This applies, in particular, to the designation 'planets.' The word 'planet' originally described 'wanderers' that were known only as moving lights in the sky. Recent discoveries lead us to create a new definition, which we can make using currently available scientific information.

The IAU therefore resolves that planets and other bodies, except satellites, in our Solar System be defined into three distinct categories in the following way:

- A planet is a celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (c) has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit.

- A 'dwarf planet' is a celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, (c) has not cleared the neighborhood around its orbit, and (d) is not a satellite.

- All other objects, except satellites, orbiting the Sun shall be referred to collectively as 'Small Solar System Bodies.'"

Debate – and Discoveries – Continue

Astronomers and planetary scientists did not unanimously agree with the IAU's definitions. To some it appeared that the classification scheme was designed to limit the number of planets; to others it was incomplete and the terms unclear. Some astronomers argued that location (context) is important, especially in understanding the formation and evolution of the solar system.

One idea is to simply define a planet as a natural object in space that is massive enough for gravity to make it approximately spherical. But some scientists object that this simple definition does not take into account what degree of measurable roundness is needed for an object to be considered round. In fact, it is often difficult to accurately determine the shapes of some distant objects. Others argue that where an object is located or what it is made of do matter and there should not be a concern with dynamics; that is, whether or not an object sweeps up or scatters away its immediate neighbors, or holds them in stable orbits.

So, the lively planethood debate continues.

As our knowledge deepens and expands, the more complex and intriguing the universe appears. Researchers have found hundreds of extrasolar planets, or exoplanets, that reside outside our solar system. There may be billions of exoplanets in the Milky Way, and some may be habitable (have conditions favorable to life). Whether our definitions of planet can be applied to these newly found objects remains to be seen.