NASA-supported scientists are among a team of researchers who have examined whether or not future missions to icy ocean worlds could spot a single bacterial cell, or just small pieces of bacteria, in a single grain of ice using mass spectrometry.

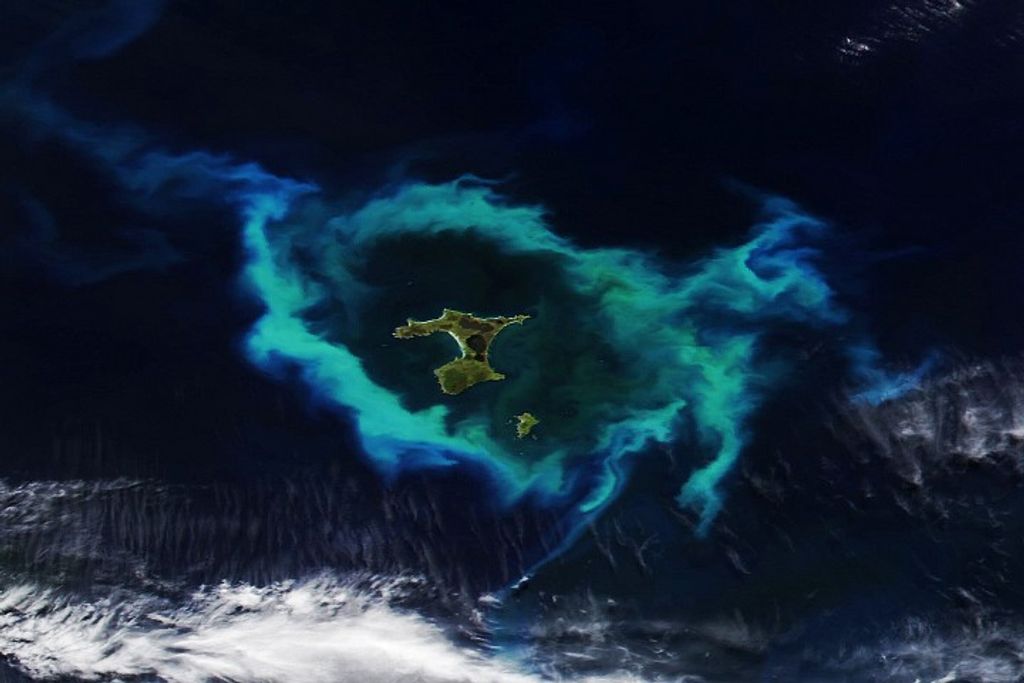

When NASA’s Cassini mission flew past Saturn’s moon Enceladus, the spacecraft spotted plumes of material emitting from the tiny moon. The source of this material is thought to be Enceladus’ subsurface ocean. Similar features could exist on other icy ocean worlds, and being able to analyze such material in detail could allow astrobiologists to determine the habitability of subsurface oceans, and maybe even spot biosignatures.

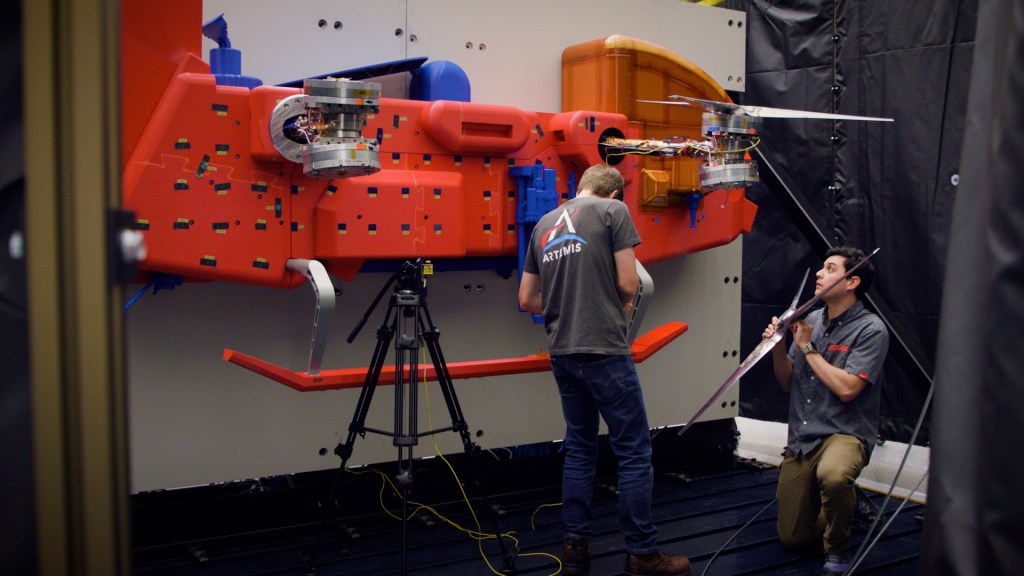

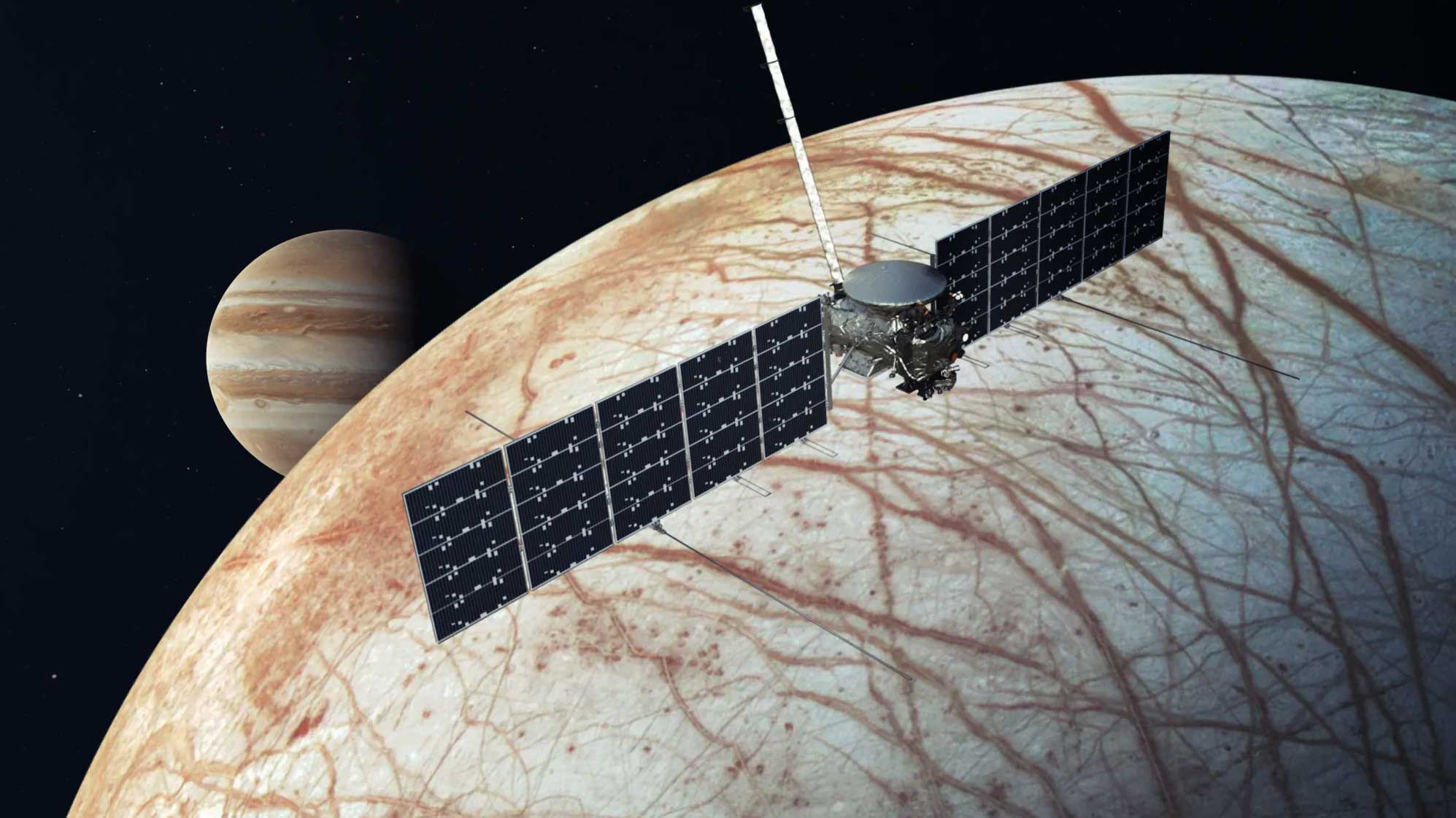

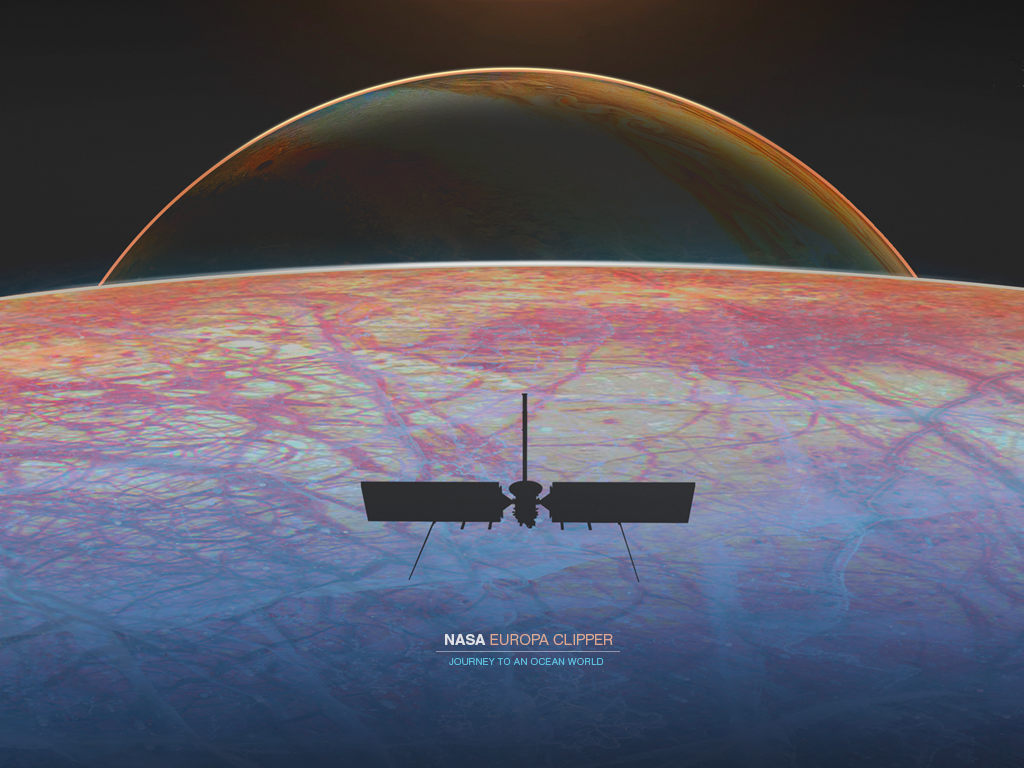

By obtaining mass spectra resulting from impacts of ice grains containing single bacterial cells (or fractions of cells), researchers were able to determine how bacteria in ice grains from ocean worlds might look to instruments on future missions, such as the SUrface Dust Analyzer (SUDA) onboard NASA’s soon-to-launch Europa Clipper.

Based on the results, the team believes that future instruments similar to SUDA could identify spectral characteristics of bacteria (or tiny pieces of bacteria) in plume material. This is the case even when a spacecraft is taking measurements while flying past a world at speeds of 4 to 6 kilometers per second.

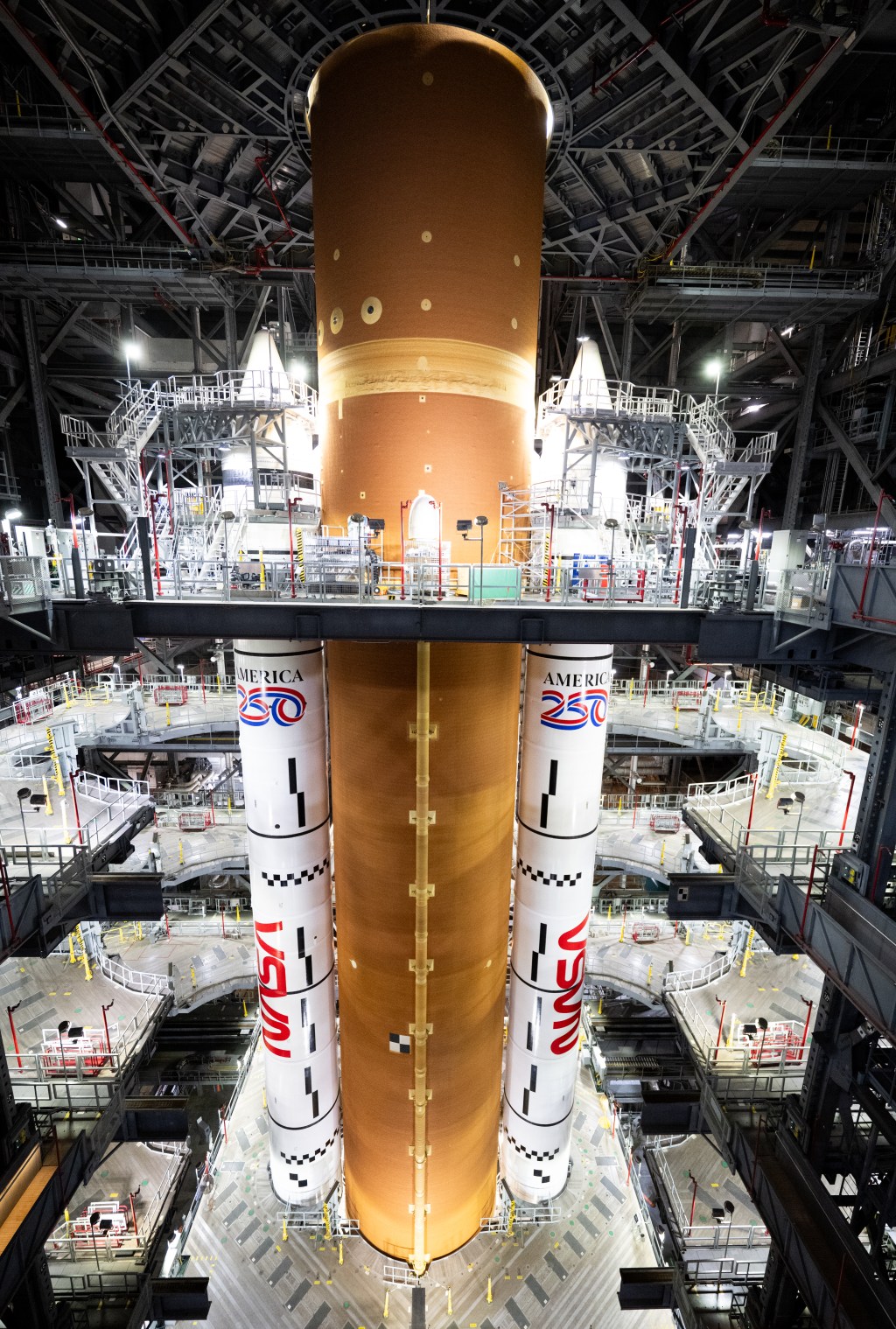

NASA’s next mission to an icy ocean world is the Europa Clipper, scheduled to launch later this year. Europa Clipper is not a search for life mission, but it will attempt to determine whether there are places below the surface of Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, that could support life.

The study, “How to identify cell material in a single ice grain emitted from Enceladus or Europa,” was published in the journal Science Advances.

In a previous study, NASA-supported scientists also looked at how instruments like SUDA could be used to identify transition metals in ice grains, providing clues about the oxidation state of subsurface oceans. This information could help scientists understand whether or not hydrothermal processes play a role in ocean chemistry and ultimately the habitability of such worlds. The study “Probing the Oxidation State of Ocean Worlds with SUDA: Fe (ii) and Fe (iii) in Ice Grains,” was published in The Planetary Science Journal.