2018 - 2019

How to Rotate Crops

A perennial question facing America’s 3.4 million farmers is how to handle crop rotation. Farmers planning their growing seasons have to decide: is rotating crops worth the extra effort? What crops perform best in rotation, and in what order? Do local weather conditions make a difference?

New research supported by NASA’s Harvest program has answers that could help farmers increase their yields. Rather than just studying the effect of crop rotation on a few fields in a controlled setting, researchers used satellite observations and machine learning to analyze the effect of rotation on a large scale in real-world conditions across multiple countries. The new work was led by researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Stanford University, and was primarily based on data collected by the Landsat program.

Their findings for fields in the U.S. aligned with common wisdom and practice among American farmers. “The bottom line was that rotation had a positive effect on yields,” said Dan Kluger, a postdoctoral fellow at MIT and the study’s lead author. The results support long-standing practices and previous research showing that crop rotation benefits farmers by minimizing pressure from pests and weeds, keeping soil microbial communities healthy, and retaining soil fertility with less use of fertilizer.

But the researchers also found exceptions and nuances based on weather conditions and the sequence of the crop rotation. For instance, fields that grew corn and then soybeans, or soybeans and then spring wheat, saw significant increases (about 8 percent) in yields compared to those where the same crop was grown each year. Growing soybeans or winter wheat before corn saw more modest increases in yields (2.5 percent and 0.9 percent, respectively). However, fields rotated from soybeans to winter wheat saw a sizable decrease (about 12 percent) in yields.

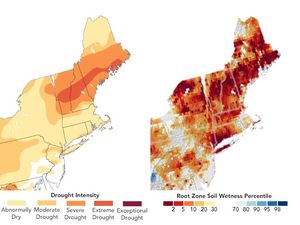

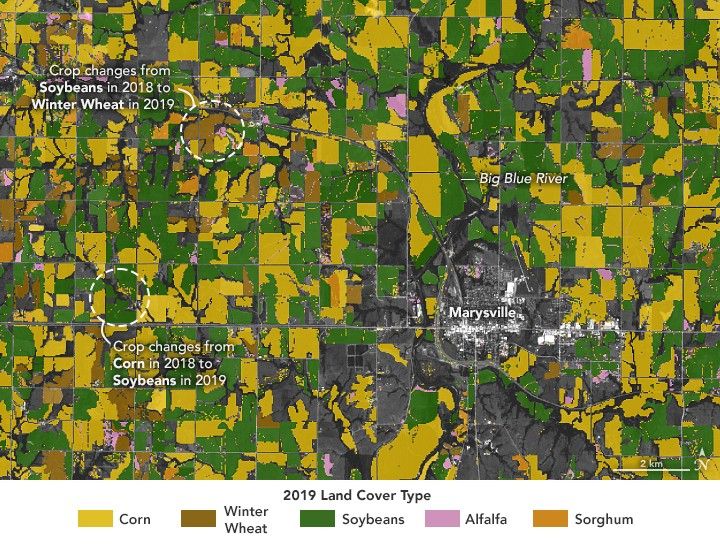

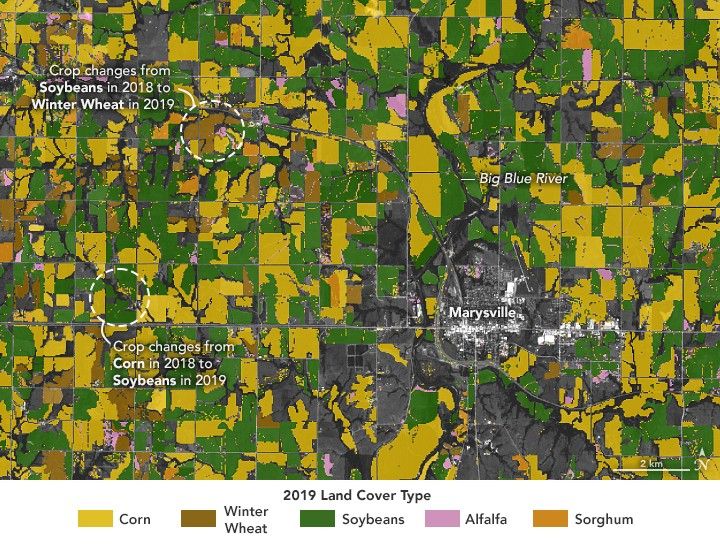

The maps above, based on the Cropland Data Layer, show one example of an area in northeast Kansas around Marysville where some of these rotation sequences were in practice. The image on the left shows crops grown in 2018, and the image on the right shows crops grown in 2019 on the same fields. Many fields rotated between corn (yellow) and soybeans (green), though some had winter wheat (brown) and other crops in the mix as well. The Cropland Data Layer, also used in the new research, is derived from Landsat observations.

“This part of Kansas is interesting because we see rotation happening that helped yields and some that probably hurt,” said Kluger. The poorer performance of winter wheat after soy is likely the result of delayed winter wheat planting. Given that soybeans are harvested late in the year, farmers growing winter wheat after soybeans typically plant a few weeks later, limiting the time that wheat has to mature. The comparatively modest yield increases for corn when preceded by soybeans (just 2.5 percent) were likely related to reduced fertilizer use, Kluger explained. Legumes like soy beans are known for “fixing” nitrogen naturally, providing a natural boost to soil fertility and prompting many farmers to cut back on synthetic fertilizer after growing legumes to reduce costs.

Since temperature and precipitation patterns are changing over time, the researchers also investigated if weather conditions had any bearing on the effectiveness of crop rotation patterns. “We found rotation generally had a greater impact in rainier conditions for corn, soybeans, and wheat,” said Kluger, attributing this to the fact that rainy conditions bring more intense pest and weed pressures that are eased by rotation.

Also, there are differences in how well residue from various crops traps snow and keeps soil moist. Wheat residue, for instance, retains snow much more effectively than sunflowers and soybeans, meaning crop rotations involving sunflower and soybeans are less effective at increasing yields in dry environments, where wheat monoculture is comparatively successful.

The researchers also found that for soybean yields the benefits of crop rotation were greater in warmer conditions, likely because warm weather intensifies pressure from harmful pests, which rotation more effectively mitigates. However, growing soybeans before corn or wheat led to less impressive yield gains in warm conditions, likely because soybeans are known to fix nitrogen less effectively at warmer temperatures and because corn and wheat monocultures can be less nitrogen limited at warmer temperatures, added Kluger.

Farmers are wise to consult local experts who know the nuances of what works best in their area, Kluger said. “But we hope that these results are broadly useful and can help people make decisions about what to grow.” One of the strengths of the research is that it is based on real-world conditions rather than controlled conditions on an experimental farm, which might not account for economic constraints, cultural norms, or other circumstances that influence farmers, he added.

Most farmers in the U.S. rotate their crops. However, previous research indicates that 18 percent of corn, 14 percent of wheat, and 6 percent of soybeans are grown continuously, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service.

References & Resources

- George Mason University (2025) CropScape. Accessed July 25, 2025.

- Kluger, D., et al. (2025) Evaluating crop rotations around the world using satellite imagery and causal machine learning. arXiv preprint 2506.02384. Accessed July 25, 2025.

- Kluger, D. et al. (2022) Combining randomized field experiments with observational satellite data to assess the benefits of crop rotations on yields. Environmental Research Letters, 17, 044066.

- Kluger, D., via Medium (2022, June 1) Combining experiments and satellite observations to measure yield benefits from crop rotation. Accessed July 25, 2025.

- Malik, A.I. et al. (2025) Exploring the plant and soil mechanisms by which crop rotations benefit farming systems. Plant and Soil, 507,1-9.

- NASA Harvest (2025) Home. Accessed July 25, 2025.

- NASA Earthdata (2025) Agriculture Production. Accessed July 25, 2025.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (2024) Crop Sequence Boundaries. Accessed July 25, 2025.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Michala Garrison, using Cropland data from USDA NASS and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey . Story by Adam Voiland .