Today’s story is the answer to the July 2025 puzzler.

In contrast with the snow-covered landscape of winter, Iceland in spring and summer displays areas of vivid color. One of those sites lies near Múlajökull, a surge-type piedmont glacier bordered by lakes that resemble an artist’s vibrant palette.

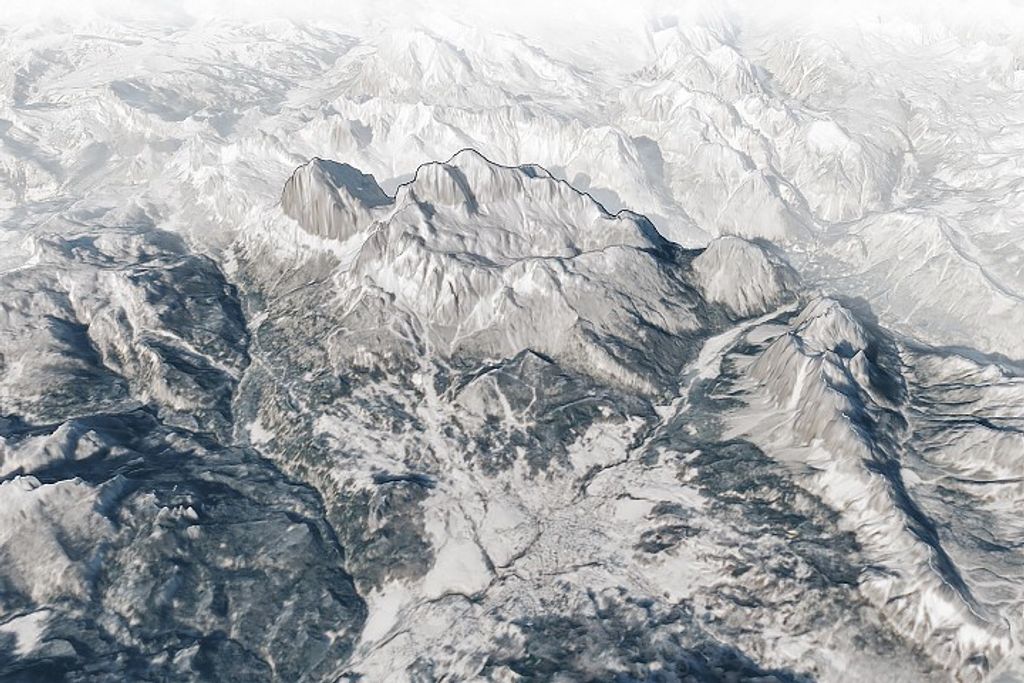

The OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat 8 acquired these images on June 14, 2025. The Múlajökull glacier (above) flows from the southeast side of Hofsjökull, Iceland’s third-largest ice cap, visible in the wide view below.

Surge-type glaciers undergo episodes of intense, rapid ice flow that interrupt periods of calm, or quiescence, when ice flow stagnates. Múlajökull has surged eight times since 1924, but in 2025, the glacier was in a period of quiescence and retreating at its front.

All this rapid advance and retreat of glacial ice has left its mark on the landscape. For instance, periods of surging produced terminal moraines—ridges of debris shoveled by the glacier and deposited at its terminus. The outermost moraine visible in this scene was likely formed between 1717 and 1760 as the glacier reached its maximum extent of the Little Ice Age.

The glacier’s retreat has uncovered a field of drumlins—elongated hills that developed below the ice. According to Neal Iverson, an emeritus professor at Iowa State University, drumlin fields exposed by modern retreating glaciers are uncommon. That makes the drumlins at Múlajökull a valuable site for scientists studying how the features grow and evolve. Iverson and colleagues previously used a mix of on-site observations and computer models to suggest that these drumlins were shaped by the uneven erosion of the ground as the glacier slipped over undulations in the landscape—not by the glacier depositing sediment as it moved.

With the glacier’s retreat, colorful lakes have filled the depressions between drumlins. Natasha Lee, a glaciologist and remote sensing expert at Northumbria University, has studied lakes across Iceland and says that the variation in color is due to different concentrations of sediment in the water. “We expect this to be the case at Múlajökull, too,” she said.

Lakes close to the glacier are newer and tend to receive meltwater rich in sediment, which makes them appear brown, Lee said. In contrast, lakes farther from the glacier are older and contain less suspended sediment, which is why they appear blue. Exceptions include several old, dark-green lakes, where algae and plants have grown, and a handful of brown lakes far from the glacier that receive meltwater from proglacial streams.

References & Resources

- Copernicus (2023, June 4) The Múlajökull glacial tongue in Iceland. Accessed July 29, 2025.

- Eos (2018, February 8) A New Model of Drumlin Formation. Accessed July 29, 2025.

- Iverson, N. R., et al. (2017) A Theoretical Model of Drumlin Formation Based on Observations at Múlajökull, Iceland. JGR Earth Surface, 122(12), 2302-2323.

- Lee, N., et al. (2024) A Temporal Study of the Proglacial Lakes Surrounding Múlajökull Outlet Glacier, Iceland Between 1987 and 2021. EGU General Assembly 2024, Vienna, Austria, EGU24-2200.

- McCracken, R. G., et al. (2016) Origin of the active drumlin field at Múlajökull, Iceland: New insights from till shear and consolidation patterns. Quaternary Science Reviews, 145, 243-260.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2015, November 18) Gains at Hofsjökull Ice Cap. Accessed July 29, 2025.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey . Story by Kathryn Hansen.