The Greater Kruger region in South Africa is a vast, interconnected landscape of forests, savannas, and grasslands that includes Kruger National Park and several private and community nature reserves near the park. It’s a haven of biodiversity that harbors the “Big Five” game animals along with rare and endangered wildlife such as pangolins, cheetahs, and ground hornbills.

It’s also a dynamic region, with fast-growing towns to the west, extensive fuelwood and timber harvesting, a thriving tourism industry, widespread agriculture, and pockets of mining. Given the potential for conflict between people and wildlife, it has also become a focal point of “rewilding”—an effort involving the park and several nearby nature reserves to restore wildlife habitat and more natural migration patterns by removing fences, returning pasture and farmland to nature, and rethinking the distribution of artificial watering holes.

From the 1960s through the 1990s, many of the reserves were fenced, preventing animals from moving freely between them and the national park. Starting in the 1990s, reserves began removing fences, creating a rare opportunity for scientists to study how large-scale changes—such as rapid increases in elephant populations—might affect vegetation and ecosystems.

Scientists from Jody Vogeler’s lab at Colorado State University, for instance, are leading an ongoing NASA-funded project aimed at assessing rewilding-driven changes and helping wildlife managers and policymakers use remote sensing to support decision-making in the region. As part of the effort, the researchers published a draft study in summer 2025 that detailed an innovative technique for fusing several types of satellite data to assess changes in the region’s woody vegetation across three dimensions.

“We’re translating the surface data into metrics that are relevant to how land managers make decisions and monitor their landscape,” said David Bunn, a professor of forest resources management at the University of British Columbia. “What managers need to know is: What is the structural change in the vegetation, and how does that influence habitat there?”

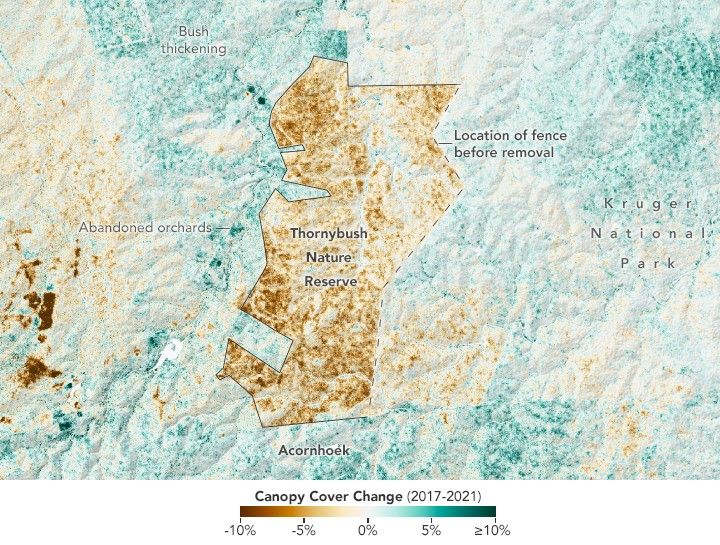

One trend that stood out in time-series maps of the region was the impact of rewilding on woody vegetation in Thornybush, a private nature reserve west of Kruger National Park. In 2017, managers removed fences along the eastern side of the reserve, reconnecting more than 140 square kilometers (54 square miles) of land with adjacent nature reserves and the national park.

From 2017 to 2019, the elephant population in Thornybush surged from 55 to 770, according to Bunn. The change coincided with a sharp reduction in vegetation height and density associated with elephant browsing. High densities of elephants can limit woody growth by uprooting small trees, stripping bark from larger trees, and pushing trees over to reach leaves and bark while browsing, Bunn explained. This counteracts the natural process of bush thickening, which occurs as trees and shrubs fill in open areas over time that were previously grasslands or farmland.

The map above depicts changes in canopy cover—the portion of the landscape covered by trees—in and around Thornybush from 2017 to 2021. The researchers found that canopy cover in some areas dropped by more than 20 percent (brown). Meanwhile, areas to the west and south that were still fenced off saw an increase in tree canopy cover (green).

While localized increases are mainly due to regrowth after recent fires or the clearing or abandonment of farmland, other factors may be contributing to the widespread trend toward bush thickening. Among them: rising carbon dioxide levels, compensatory growth after fuelwood harvesting, and changes in livestock management practices, Vogeler explained.

The map is based on data acquired by the GEDI (Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation) instrument on the International Space Station. GEDI uses light detection and ranging technology called lidar to sample the three-dimensional structure of forests, including tree height and density. The researchers combined GEDI data with optical observations from Landsat and data from the PALSAR (Phased Array L-band Synthetic Aperture Radar) on Japan’s ALOS-1 and ALOS-2 satellites, as well as soil and topography data.

The fusion of data from GEDI, Landsat, and ALOS provides insights and forecasting capabilities that would not be possible using any single data source, Vogeler said, because each sensor has particular strengths. Landsat sensors and PALSAR, for instance, offer wall-to-wall coverage while GEDI only samples small areas. Since it’s a type of radar, PALSAR can also detect details of the structure of woody vegetation that the others cannot and can make observations through clouds.

The modeling and mapping techniques developed by Vogeler’s lab are designed to help land managers and policymakers anticipate and balance the needs of the region’s many stakeholders. For example, managers could use the information to evaluate how elephant browsing affects vegetation structure in specific areas or weigh tradeoffs between fuelwood or timber harvesting and the needs of wildlife.

“Proper management is critical for developing plans that will help people, wildlife, and ecosystems coexist,” Bunn said. “We’re also taking the science directly to stakeholders in South Africa through training sessions, meetings, and workshops,” added Vogeler. “We want people on the ground to understand our data, help us check and improve it, and use it to make decisions.”

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and data from Filippelli, S., et al. (2025). Photo courtesy of David Bunn (The University of British Columbia). Story by Cathy Ching and Adam Voiland.

References & Resources

- Africa Geoportal (2022) South African Protected Areas. Accessed November 20, 2025

- Filippelli, S., et al. (2025) Tracking savanna vegetation structure in South Africa by extension of GEDI canopy metrics with Landsat, Sentinel-2, and PALSAR. BioRxiv.

- Lorimer, J., et al. (2015) Rewilding: Science, Practice, and Politics. Annual Reviews, 40, 39-62.

- ORNL DAAC (2025) Greater Kruger National Park, GEDI Canopy Metrics, 2007-2022. Accessed November 20, 2025

- Vogeler Lab (2025) Characterizing savanna vegetation change and wildlife habitat in the Kruger National Park region, South Africa. Accessed November 20, 2025

- Vogeler, J. (2025) Biodiversity, connectivity, and ecological forecasting. Accessed November 20, 2025.