How Can Webb Study the Early Universe?

When astronomers use a telescope to look farther away, they are also looking back in time.

When we look out into the universe, we see a variety of galaxy shapes: some with magnificent spiraling arms, others that appear to glow like giant lightbulbs. These spiral and elliptical galaxies haven’t always had these familiar shapes, though. Early research based on observations by the James Webb Space Telescope have already shown that galaxies in the early universe were often flat and elongated, like surfboards and pool noodles — and are rarely round, like volleyballs or frisbees. A big question in astronomy is how these early, modest groupings of stars evolved into the grand structures we see today.

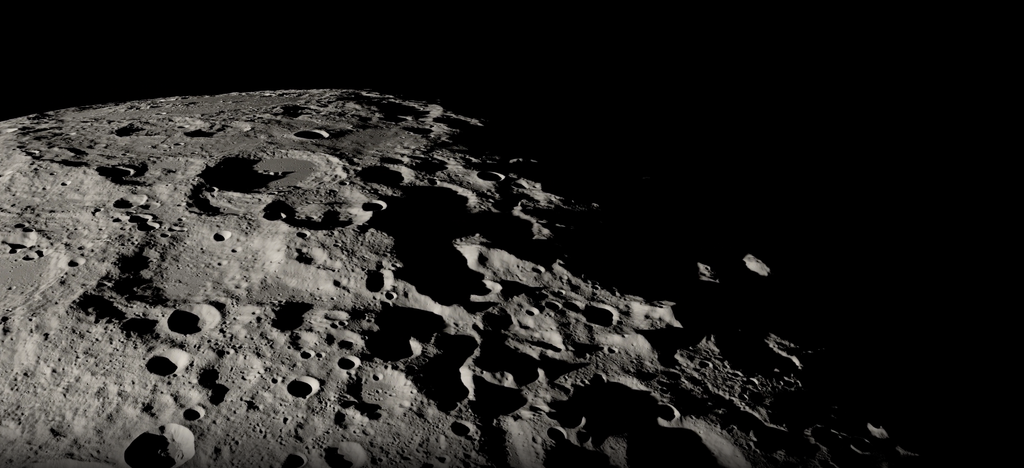

When astronomers use a telescope to look farther away, they are also looking back in time. The reason is simple: Light needs time to travel through space. Even the light from the Moon is 1.3 seconds old when we see it on Earth. The light from the most distant galaxies that Webb has viewed left those galaxies over 13 billion years ago. That means we see the galaxies as they were a few hundred million years after the big bang.

But there’s another complication. As the universe expands, light is stretched into longer and longer wavelengths, beyond the visible portion of the spectrum, into infrared light. By the time visible light from extremely distant galaxies reaches us, it appears as infrared light. Webb observes infrared wavelengths, seeing deeper into that portion of the spectrum.

Webb is engineered to observe the earliest stages of galaxy formation and astronomers are already using its data to study the formation of very early galaxies. Over time, Webb may help us learn how small galaxies in the early universe merged to form larger galaxies. Finally, Webb is capable of revealing the general population of stars and galaxies that existed only a few hundred million years after the big bang. This expanded sample of early galaxies will give astronomers a better idea of how galaxies looked as they first came into being and help them map the universe’s overall structure.

The Hidden Universe

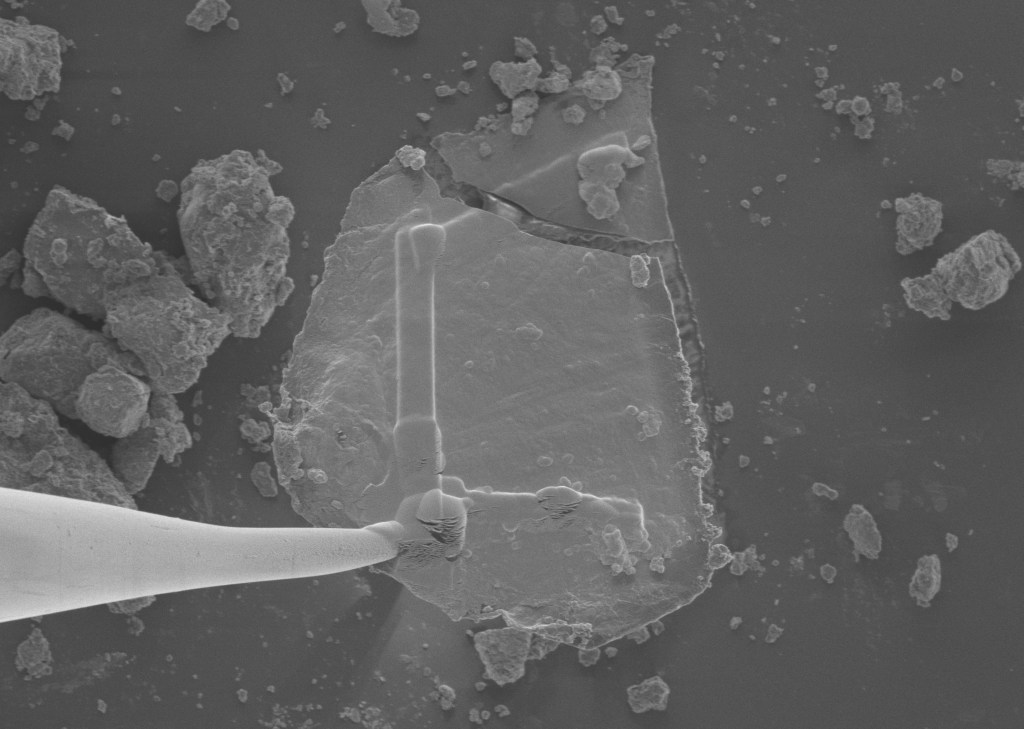

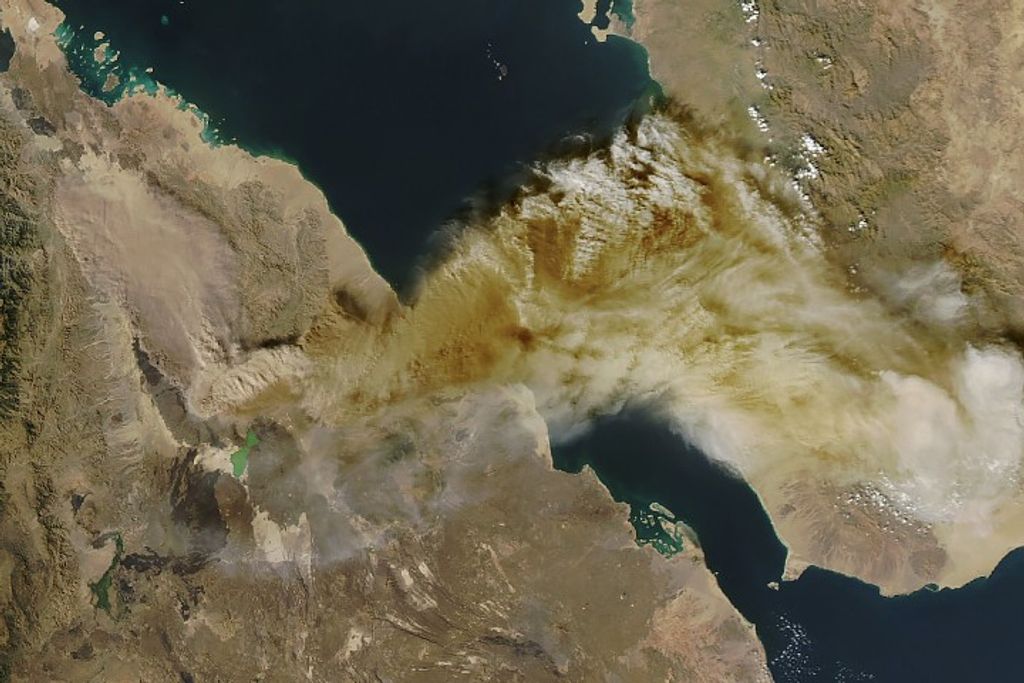

Webb's infrared instruments allow us to see inside regions of galaxies that are obscured by dust when they are viewed in visible light, which illuminates the process and context of star formation. Webb can also study regions of star formation in merging galaxies, revealing how these galactic encounters trigger and alter the course of star formation as their gaseous components collide and mix.

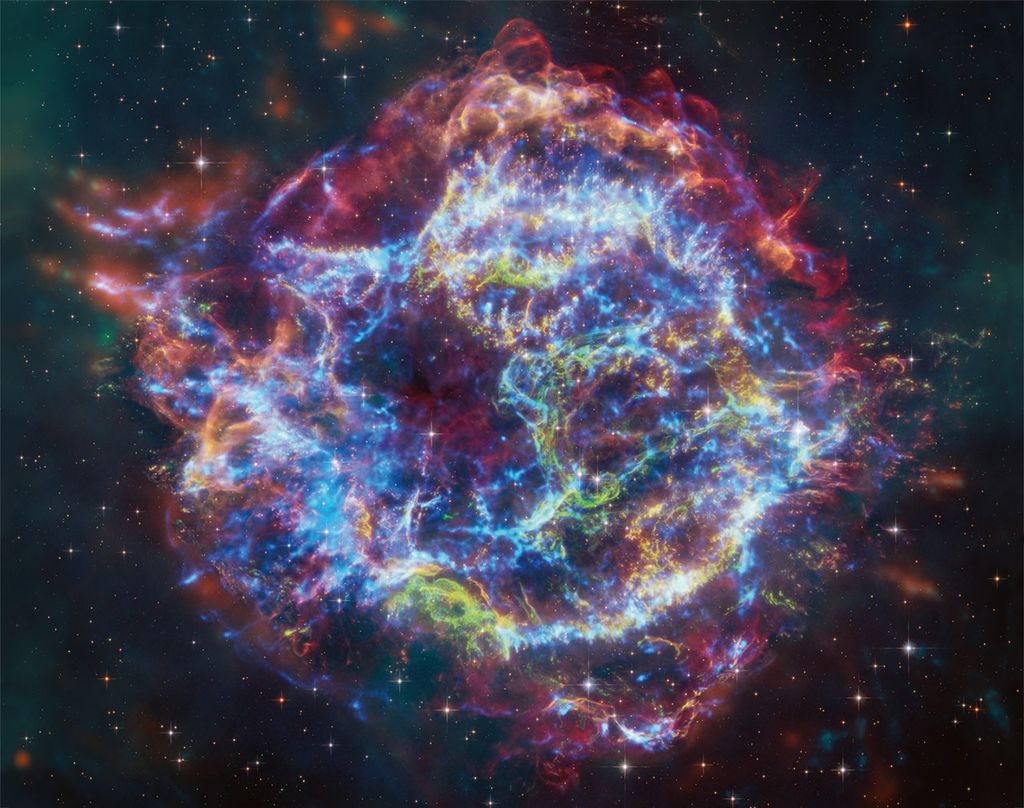

In addition to studying previously shrouded stellar nurseries, astronomers are using Webb to explore an era known as the Dark Ages and the time immediately following it, the Era of Reionization. About 378,000 years after the big bang, as the universe cooled and expanded, electrons and protons began to bind together to form hydrogen atoms. As the last of the light from the big bang faded, the universe would have been a dark place, with no sources of light within the cooling hydrogen gas. Eventually, the gas coalesced to form stars and eventually galaxies. Over time, most of the hydrogen was "reionized," turning it back into protons and electrons, and allowing light to travel across space once again.

Webb has already revolutionized our understanding of this time period. Researchers using Webb showed for the first time that galaxies’ stars emitted enough light to heat and ionize the gas around them, clearing our collective view over hundreds of millions of years. Before this, researchers didn’t have definitive evidence of what caused reionization. Astronomers will continue to use Webb's sensitive infrared instruments to study the process of reionization on large and small scales to understand the details of how the hydrogen gas between galaxies was ionized.