World of Change: Columbia Glacier, Alaska

- World of Change: Padma River

- World of Change: Sprawling Shanghai

- World of Change: Ice Loss in Glacier National Park

- World of Change: Snowpack in the Sierra Nevada

- World of Change: Development of Orlando, Florida

- World of Change: Growing Deltas in Atchafalaya Bay

- World of Change: Coastline Change

- World of Change: Managing Fire in Etosha National Park

- World of Change: Green Seasons of Maine

- World of Change: Athabasca Oil Sands

- World of Change: Seasons of the Indus River

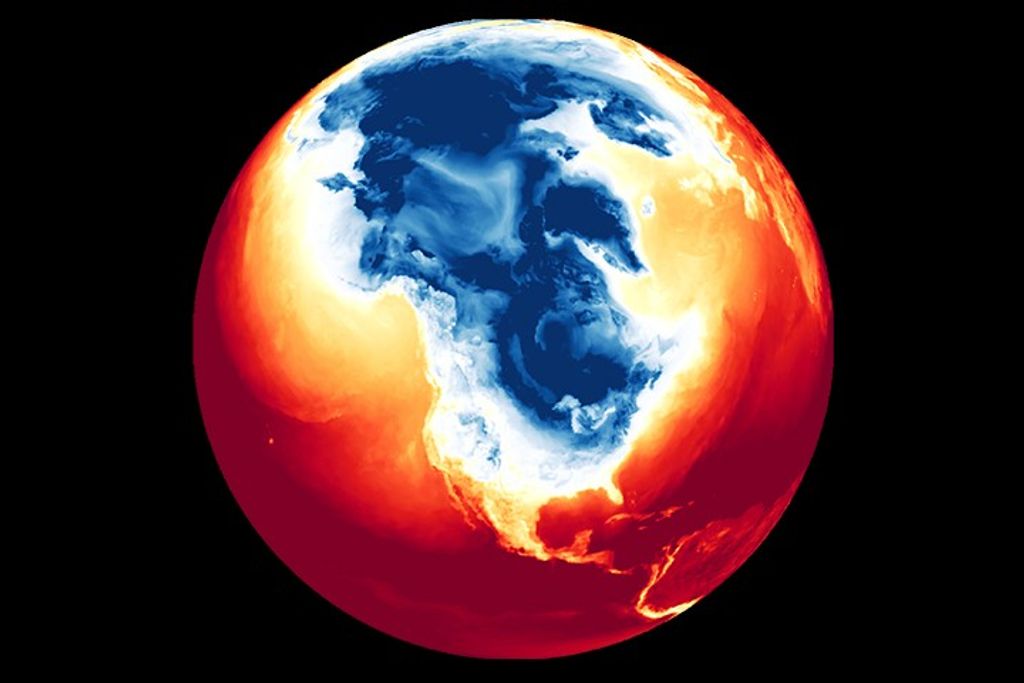

- World of Change: Global Temperatures

- World of Change: Seasons of Lake Tahoe

- World of Change: Devastation and Recovery at Mt. St. Helens

- World of Change: Collapse of the Larsen-B Ice Shelf

- World of Change: Mountaintop Mining, West Virginia

- World of Change: Yellow River Delta

- World of Change: Drought Cycles in Australia

- World of Change: El Niño, La Niña, and Rainfall

- World of Change: Severe Storms

- World of Change: Burn Recovery in Yellowstone

- World of Change: Global Biosphere

- World of Change: Antarctic Ozone Hole

- World of Change: Amazon Deforestation

- World of Change: Antarctic Sea Ice

- World of Change: Shrinking Aral Sea

- World of Change: Arctic Sea Ice

- World of Change: Water Level in Lake Powell

- World of Change: Mesopotamia Marshes

- World of Change: Solar Activity

- World of Change: Urbanization of Dubai

The Columbia Glacier descends from an icefield 3,050 meters (10,000 feet) above sea level, down the flanks of the Chugach Mountains, and into a narrow inlet that leads into Prince William Sound in southeastern Alaska. It has long been an archetype of the world’s most rapidly changing glaciers.

The Columbia is a large tidewater glacier, flowing directly into the sea. When British explorers first surveyed it in 1794, its nose—or terminus—extended south to the northern edge of Heather Island, near the mouth of Columbia Bay. The glacier held that position until 1980, when it began a rapid retreat that continues today.

These false-color images, captured by Landsat satellites, show how the glacier and the surrounding landscape have changed since 1986. The images were collected by similar sensors—the Thematic Mapper (TM), the Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+), and the Operational Land Imager (OLI)—on four different Landsat satellites (4, 5, 7, and 8).

The images above combine shortwave-infrared, near-infrared, and green portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. With this combination of wavelengths, snow and ice appear bright cyan, vegetation is green, clouds are white or light orange, and open water is dark blue. Exposed bedrock is brown, while rocky debris on the glacier’s surface is gray.

Since the 1980s, the glacier’s Main Branch has retreated more than 20 kilometers (12 miles), moving past Terentiev Lake and a rocky outcrop north of Great Nunatak Peak. In some years, the terminus retreated more than a kilometer, though the pace has been uneven. The movement of the terminus stalled between 2000 and 2006, for example, because the Great Nunatak Peak and Kadin Peak (directly to the west) constricted the glacier’s movement and held the ice in place.

As the glacier terminus has retreated, the Columbia has thinned substantially, as shown by the expansion of brown bedrock areas in the Landsat images. Since the 1980s, the glacier has lost more than half of its total thickness and volume. Rings of freshly exposed rock, known as trimlines, became especially prominent around the inlet throughout the 2000s.

Just south of the terminus, a layer of floating ice is dimpled with chunks of icebergs that have broken off, or calved, from the glacier and rafted together. The area and thickness of this layer, called the ice “mélange,” vary depending on recent calving rates and ocean conditions. In most of the images in the series (particularly 1989 and 1995), the mélange extends south to Heather Island, marking the point at which the glacier reached its greatest extent.

Like bulldozers, glaciers lift, carry, and deposit sediment, rock, and other debris from Earth’s surface. This mass accumulates on the ice’s leading edges in piles called moraines. The Columbia’s moraine created a shallow underwater ridge, or shoal, that prevents the mélange from drifting beyond it.

The structure of Columbia’s moraine played a large role in the stability of the glacier before 1980. Like other tidewater glaciers, the Columbia built up a moraine over time, and the mixture of ice and rock functioned like a dam keeping out the sea. It was supported on one end by the shoreline and by the underwater terminal moraine at the other. When the glacier retreated off the moraine around 1980, the terminus lost a key source of support. Once freed from this anchoring point, the grinding and dragging between the sea floor and the massive block of ice was reduced, increasing the rate at which ice flowed forward and icebergs calved from the glacier.

Between 2007 and 2010, part of the terminus began to float as it passed through deep water between the Great Nunatak Peak and Kadin Peak. This changed the way icebergs calved significantly. When the Columbia was grounded, calving occurred at a fairly steady rate, and the bergs that broke off were small. When the glacier began to float, larger chunks of ice tended to break off, as seen in the image from 2009.

The retreat has also changed the way the glacier flows. In the 1980s, there were three main branches. The medial moraine, a line of debris deposited when separate channels of ice merge (seen here as a line in the center of the 1986 image), served as a dividing line between two of the main branches. In 1986, there was a branch to the west of the medial moraine (West Branch), a large branch that flowed to the east of it (Main Branch), and a smaller branch that flowed around the eastern side of Great Nunatak Peak.

As the Columbia lost mass and thinned, the flow in the smallest branch stalled, reversed, and eventually began flowing to the west of Great Nunatak Peak. By 2011, the retreating terminus essentially split the Columbia into two separate glaciers, with calving now occurring on two distinct fronts.

The West Branch was thought to have stabilized by 2011, but it surprised scientists with an unexpected retreat that shows up in the 2013 image. By 2019, scientists suggested the branch was at the limit of its tidewater retreat and was no longer capable of calving icebergs.

In 2014, researchers found that the Main Branch had thinned so much that it no longer had traction against the bed. With less traction, the glacier can be affected by tidal motion as far as 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) upstream, leaving the Main Branch unstable again. The branch resumed retreat until it became constricted for several years by the rocky outcrop north of the Great Nunatak. After 2019, the glacier lost contact with this stabilizing “pinning point,” and more retreat followed.

The retreat of the Columbia Glacier contributes to global sea-level rise, mostly through iceberg calving. This one glacier accounts for nearly half of the ice loss in the Chugach Mountains. However, the ice losses are not exclusively tied to increasing air and water temperatures. Climate change may have given the Columbia an initial nudge off of the moraine, but mechanical processes help drive its disintegration. When the Columbia reaches the shoreline, its retreat will likely slow down. The more stable surface will cause the rate of calving to decline, making it possible for the glacier to start rebuilding a moraine and advancing once again.

NASA images by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, using Landsat 4, 5, 7, and 8 data from the USGS Global Visualization Viewer. Thanks to Shad O’Neel and Robert McNabb for image interpretation and editorial guidance.

References

- Berthier, E. (2010, January 17) Contribution of Alaskan Glaciers to Sea-Level Rise Derived from Satellite Imagery. Nature Geoscience.

- Krimmel, R. (2001) Photogrammetric Data Set, 1957-2000, and Bathymetric Measurements for Columbia Glacier, Alaska. U.S. Geological Survey.

- McNabb, R.W. (in press). Using Surface Velocities to Calculate Ice Thickness and Bed Topography: A Case Study at Columbia Glacier, Alaska. Journal of Glaciology.

- Rasmussen, L.A. (2011, January 17) Surface Mass Balance, Thinning, and Iceberg Production, Columbia Glacier, Alaska, 1948-2007. Journal of Glaciology.

- O’Neel, Shad. (2012) Surface Mass Balance of the Columbia Glacier, Alaska, 1978 and 2010 Balance Years. (pdf) U.S. Geological Survey Data Series.

- O’Neel, Shad. (2005, September 20) Evolving Force Balance at Columbia Glacier, Alaska, During Its Rapid Retreat. Journal of Geophysical Research.

- Post, A. (2011, September 13) A Complex Relationship Between Calving Glaciers and Climate. EOS.

- Walter, Fabien. (2010, August 7) Iceberg Calving During Transition from Grounded to Floating Ice: Columbia Glacier, Alaska. Geophysical Research Letters.