Earth planning date: Monday, July 1, 2024

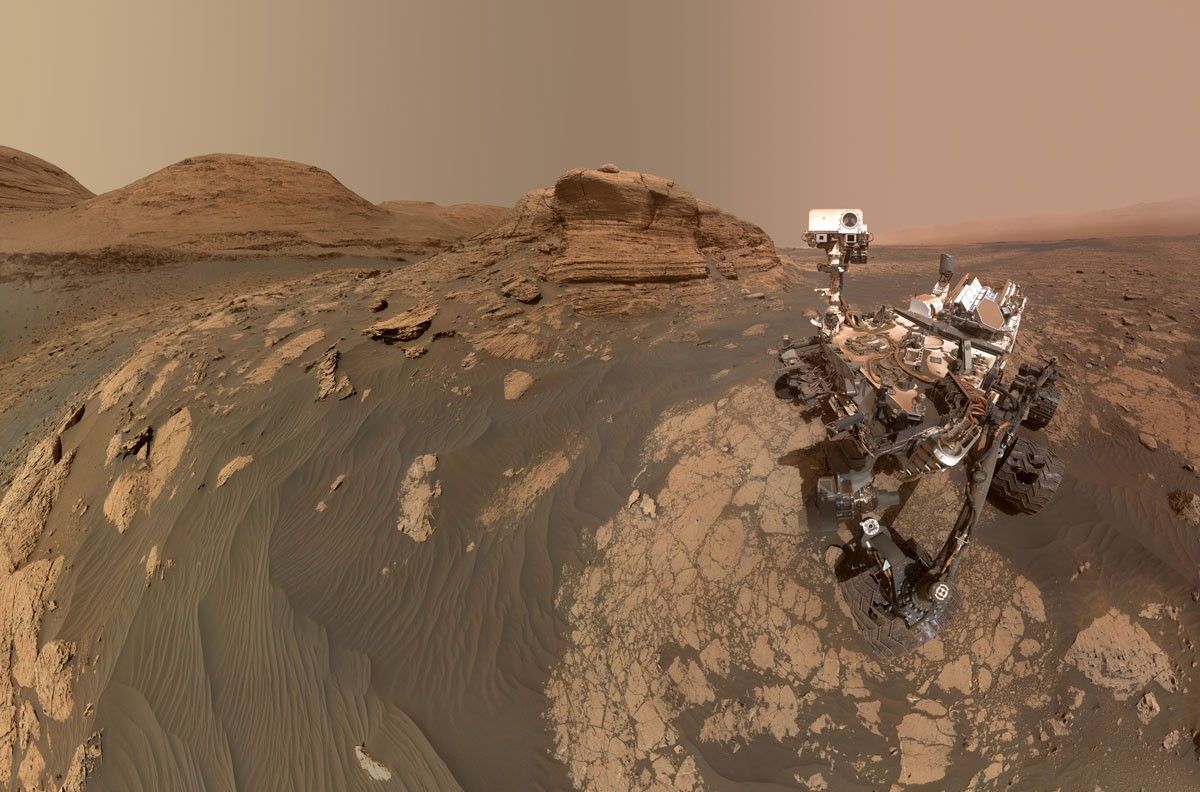

Have you ever wondered what it might look like to ride along with the rover? Probably not as much as we have here on the planning team, where we are looking at the images on a daily basis. I always wish I could walk around there myself, or drive around in a vehicle, maybe. As you likely know, we don’t even get video, “just” images. But of course those images are stunning and the landscape is unique and – apart from being scientifically interesting – so very, very beautiful. And some cameras record images so often that it’s actually possible to create the impression of a movie. The front hazard camera is among them. And that can create a stunning impression of looking out of the front window! If you want to see that for yourself, you can! If you go to the NASA interactive tool called "Eyes on the Solar System" there is a Curiosity Rover feature that allows you to do just that: simulate a drive between waypoints and look out of the window, which is the front hazard camera. Here is the link to "Experience Curiosity." The drive there is a while back, but the landscape is just so fascinating, I can watch and rewatch that any number of times!

Now, after reminiscing about the past, what did we do today? First of all: change all plans we ever had. We don’t have – as scheduled – the SAM data on Earth just yet. But we have a good portion of the sample still in the drill, and if SAM gets their data and wants to do more analysis with that sample, then we can’t move the arm as we originally had planned. Why didn’t we consider that to begin with? Normally, there isn’t enough sample for all the analysis; you may have seen this blog post: "Sols 4118-4119: Can I Have a Second Serving, Please? Oh, Me Too!" But it’s the sample that dictates how much we get to begin with, and how much we need, which only becomes clear as the data come in. And there is an unusually lucky combination here that would avoid us having to drill a second hole for getting the second helping. Instead, we just sit here carefully holding the arm still so we do not lose sample. That saves a lot of rover resources. But then, once we had settled how we adjust to keeping our current position, we also learnt that the uplink time might shift from the original slot we had been allocated to a later one… And all of this with a pretty new-to-the-role Science Operations Working Group (SOWG) chair (me) and a similarly new Geology and Mineralogy theme group science lead. Well, we managed, with lots of help from the great team around us.

Those sudden-change planning days are so tricky because there is so much more to remember. It’s not, "This is what we came to do...,” and it had been carefully pre-planned, and it is all in the notes. Instead, the pre-planning preparation doesn’t fit the new reality anymore, and all that work has to be redone. So we have to do all the pre-planning work, and the actual planning work, and sometimes also account for some “if… then…” scenarios in the same amount of time we usually have to do the planning on the basis of all the pre-planning work.

Sounds stressful? Yes, I can tell you it is!

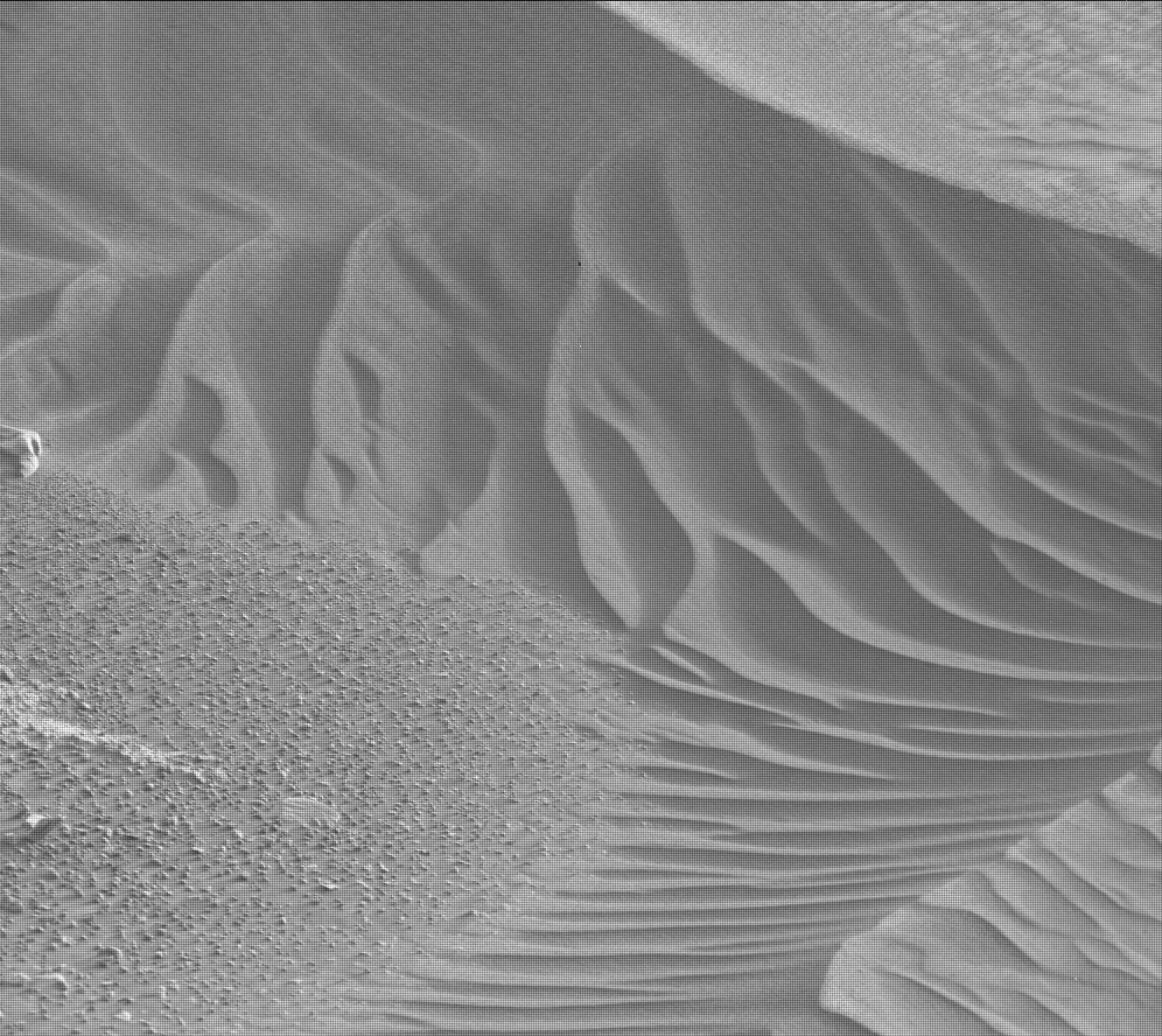

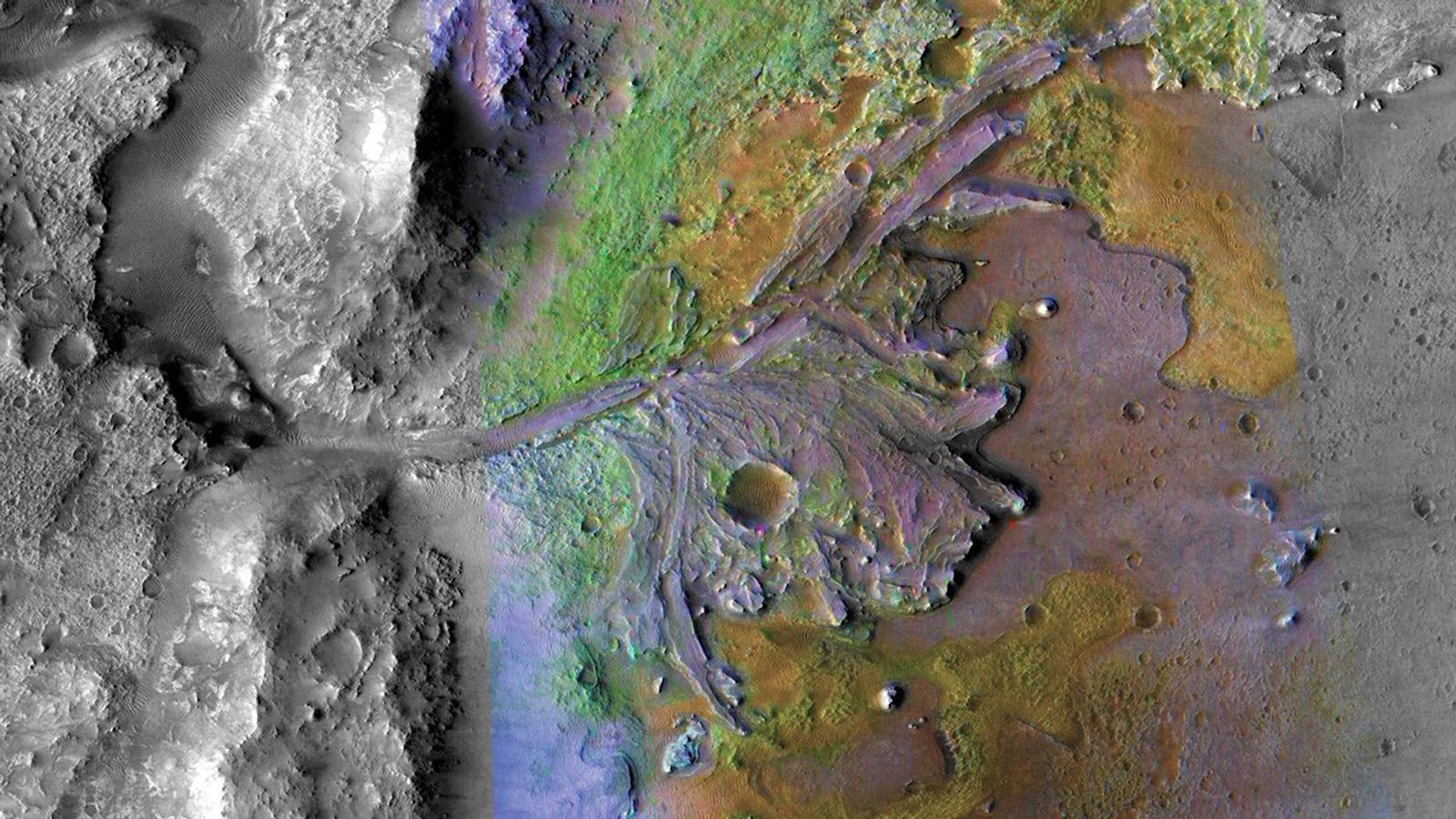

Once we had changed all the skeleton plans, the team got very excited about the extra time. This is such an interesting area, there are rocks that are almost white, there are darker rocks, very interesting sand features with beautiful ripples, so much to look at! Mars has much to offer here, so the team got to work swiftly and the plan filled up with a great set of observations. ChemCam used LIBS on the target "Tower Peak," which is one of those white-ish rocks, and on "Quarry Peak." Mastcam delivers all the pictures to go along with these two activities and gets its own science, too. These are mainly so-called "change detection" images, where the same area is pictured repeatedly to see what particles might move in the time between the two images. ChemCam uses its long-distance imaging capability to add to the stunning images they are getting from faraway rocks. They have two mosaics on a target called "Edge Bench." There is also a lot of atmospheric science in the plan; looking for dust devils and the opacity of the atmosphere are just two examples. REMS and DAN are also active throughout, to assess the wind, and the water underground, respectively. And as if that weren’t enough, CheMin also performs another night of analysis. We get to uplink a full plan, and we’ll see what the data say and what decisions we’ll make for next Wednesday.

Written by Susanne Schwenzer, Planetary Geologist at The Open University